19.2 Thyroid disorders

Thyroid physiology

Disorders of thyroid function in childhood can be divided into the following categories:

Hypothyroidism

Congenital

Incidence

The incidence of congenital hypothyroidism is 1 in 3000–5000, with some geographical variation.

Aetiology and genetics

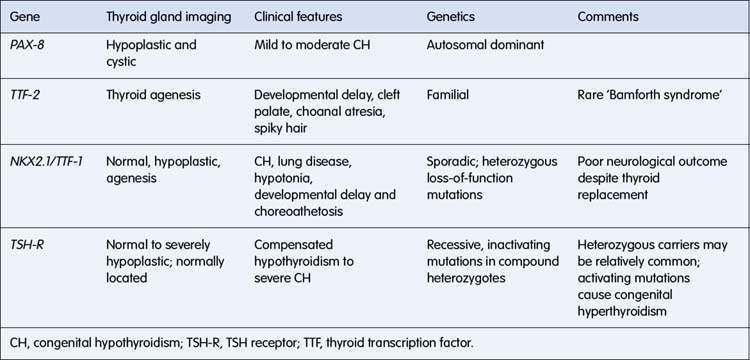

Studies in mouse models with congenital defects of thyroid development have provided the basis for molecular genetic studies in humans with congenital hypothyroidism. Mutations have been described in a number of genes, resulting in absent, misplaced, hypoplastic or unresponsive glands (Table 19.2.1). In some instances, a specific phenotype can be recognized, and prognosis is affected. For example, in individuals with the NKX2.1 mutation, neurological outcome is poor despite early thyroxine treatment.

Table 19.2.1 Mutations in genes involved in thyroid development resulting in congenital hypothyroidism

Management

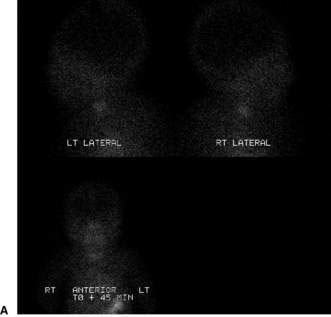

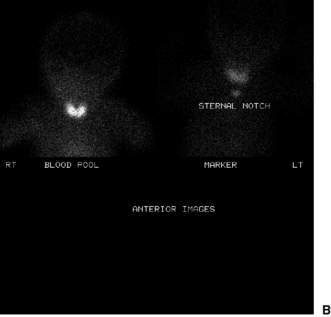

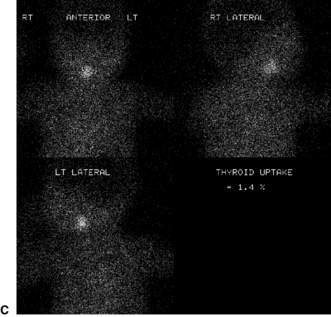

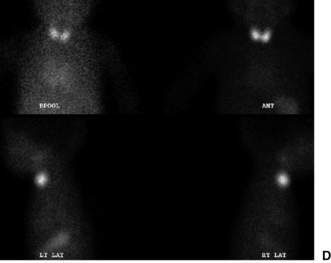

Confirmatory investigations are needed if the screening tests suggest an abnormality: repeat T4 and TSH; thyroid scan (showing absent, lingual or increased uptake of radioisotope), X-ray distal femoral epiphysis (absence implying prolonged/prenatal hypothyroidism), and assessment and imaging of the pituitary gland if indicated. Treatment involves commencement of therapy (thyroxine replacement at 8–10 μg/kg daily). Thyroid imaging results for congenital hypothyroidism of varying causes are shown in Figure 19.2.1.