Chapter 671 The Spine

Abnormalities of the spine may be present at birth (congenital), can develop during childhood or adolescence, or can result from traumatic injuries. Alterations in spinal alignment are commonly of cosmetic concern to the patient and family. Sequelae from progressive spinal deformities include pain, cardiopulmonary dysfunction, and a loss of sitting balance (nonambulators). Early detection helps to facilitate treatment and to identify and address coexisting visceral and/or neurologic problems that may be associated with a spinal deformity. A classification of common spinal abnormalities is presented in Table 671-1.

Table 671-1 CLASSIFICATION OF SPINAL DEFORMITIES

SCOLIOSIS

Idiopathic

Congenital

Neuromuscular

Myopathies

Syndromes

Compensatory

KYPHOSIS

Adapted from the Terminology Committee, Scoliosis Research Society: A glossary of scoliosis terms, Spine 1:57, 1976.

671.1 Idiopathic Scoliosis

Etiology and Epidemiology

Scoliosis is a complex, 3-dimensional deformity of the spine, with abnormalities in the coronal, sagittal, and axial planes. The diagnosis is based on a coronal plane curvature of >10 degrees using the Cobb method. Idiopathic scoliosis is a diagnosis of exclusion; other causes must be ruled out (see Table 671-1). The etiology of idiopathic scoliosis remains unknown and is likely multifactorial, involving both genetic and environmental components. Major theories have been based on genetic factors, metabolic dysfunction (melatonin deficiency, calmodulin), neurologic dysfunction (craniocervical, vestibular and oculovestibular), and biomechanical factors (asynchrony in spinal growth, anterior spinal overgrowth, and others). With regard to genetic factors, although several different modes of inheritance have been suggested (autosomal dominant, multifactorial, X-linked), a single locus has yet to be identified. Abnormalities identified in connective tissue, muscle, and bone appear to be secondary. Melatonin and calmodulin might have indirect effects, and subtle abnormalities in vestibular, ocular, and proprioceptive function suggest that abnormal equilibrium might also play a role.

Clinical Manifestations

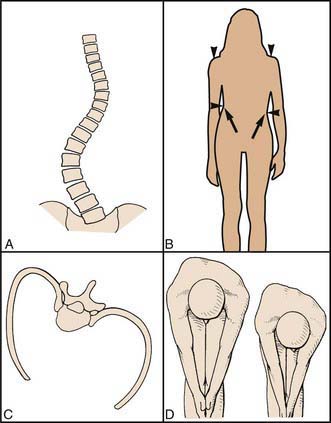

Patients usually present with a change in cosmetic appearance noted by family and/or friends or on a screening examination by a school nurse or primary care physician. The patient is evaluated in the standing position, from both the front and the side, to identify any asymmetry in the chest wall, trunk, and/or shoulders. Asymmetry of the posterior chest wall on forward bending (the Adams test) is the earliest abnormality (Fig. 671-1). Rotation of the vertebral bodies toward the convexity results in rotation and prominence of the attached ribs posteriorly. The anterior chest wall may be flattened on the concavity, due to inward rotation of the chest wall and ribs. Associated findings can include elevation of the shoulder, a lateral shift of the trunk, and an apparent leg-length discrepancy. The patient should also be evaluated from the side. The thoracic spine normally has a smooth, rounded kyphosis (20-50 degrees using the Cobb method from T3-T12) that extends down to the thoracolumbar junction, and the lumbar spine is normally lordotic (30-60 degrees using the Cobb method from T12-L5). Children normally have less cervical lordosis and more lumbar lordosis than do adults or adolescents. Typically, idiopathic scoliosis results in a loss of the normal thoracic kyphosis in the region of curvature (relative thoracic lordosis).

Radiographic Evaluation

Standing high-quality posteroanterior (PA) and lateral radiographs of the entire spine are recommended at the initial evaluation for patients with clinical findings that suggest a spinal deformity. On the PA radiograph, the degree of curvature is determined by the Cobb method, in which the angle between the superior and inferior end vertebra (tilted into the curve) is measured (Fig. 671-2). A line is drawn across the superior end plate of each end vertebra, and the angle between perpendicular lines erected from each of these is measured. Although the indications for performing MRI are variable, this modality is helpful when an underlying cause for the scoliosis is suspected based on age (infantile, juvenile curves), abnormal findings on the history and physical examination, and atypical radiographic features (curve patterns and/or specific features). Atypical radiographic findings include uncommon curve patterns such as the left thoracic curve, double thoracic curves, high thoracic curves, widening of the spinal canal, and erosive or dysplastic changes in the vertebral body or ribs. On the lateral radiograph, an increase in thoracic kyphosis or an absence of segmental lordosis might suggest the presence of an underlying diagnosis.

Treatment

Bracing

There are several options for braces (Fig. 671-3). The Milwaukee brace, employing longitudinal traction from the skull to the pelvis with lateral compression of the chest wall, can be adjusted for growth and thus is a good brace for patients with infantile or juvenile scoliosis. Underarm braces (the Boston or Wilmington braces) are less obvious and so are often preferred by adolescents. The Charleston brace provides a corrective force and is used only at night.

Surgery

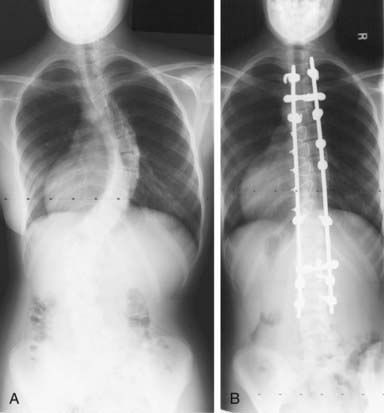

The most common procedure is an instrumented posterior spinal fusion, and the typical spinal implant construct includes 2 rods anchored to the spine by hooks, wires, and/or screws (Fig. 671-4). In the last few years there has been significant interest in using a construct with pedicle screws at each level. Although correction of the axial deformity (rotation of the rib cage) is more pronounced with this technology, it remains unclear whether patient outcomes are improved. An anterior release and fusion, performed through a thoracotomy or thoracolumbar exposure, is indicated for isolated thoracolumbar and lumbar curves, to improve correctability of stiffer curves, and to prevent curve progression (“crankshaft”) from continued anterior growth of the spine in selected patients with considerable growth remaining. A construct with multiple pedicle screws can allow the surgeon to avoid an anterior approach in many larger or stiffer curves (more powerful correction) and in younger patients (stiff enough to resist anterior spinal growth and prevent crankshaft). Thoracoscopic surgery has also been used to perform an anterior release with or without instrumentation and fusion, but this technique has been used much less often since the advent of thoracic pedicle screws. For idiopathic thoracolumbar and lumbar curves, an anterior fusion with instrumentation (usually screws in the vertebral body connected to 1 or 2 rods) can be done as an alternative to save lumbar motion segments.

Barsdorf AI, Sproule DM, Kaufman P. Scoliosis surgery in children with neuromuscular disease. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:231-235.

Bunge EM, Juttmann RE, van Biezen FC, et al. Estimating the effectiveness of screening for scoliosis: a case-control study. Pediatrics. 2008;121:9-14.

de Lind van Wijngaarden RFA, de Klerk LWL, Festen DAM, et al. Scoliosis in Prader-Willi syndrome: prevalence, effects of age, gender, body mass index, lean body mass and genotype. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:1012-1016.

Dolan LA, Weinstein SL. Surgical rates after observation and bracing for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: an evidence based review. Spine. 2007;32:S91-S100.

Gillingham B, Fan RA, Akbarnia BA. Early onset idiopathic scoliosis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:101-112.

Kallmes D, Jarvik JG. Spinal augmentation research: free at last? Lancet. 2009;373:982-984.

Katz DE, Herring JA, Browne RH, et al. Brace wear control of curve progression in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:1343-1352.

Kim YJ, Lenke LJ, Kim J, et al. Comparative analysis of pedicle screw versus hybrid instrumentation in posterior spinal fusion of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2006;31:291-298.

Merola AA, Haher TR, Brkaric M, et al. A multi-center study of the outcomes of the surgical treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis using the Scoliosis Research Society (SRS) outcome instrument. Spine. 2002;27:2046-2051.

Negrini S, Minozzi S, Bettany-Saltikov J, et al: Braces for idiopathic scoliosis in adolescents (review), Cochrane Database Rev (1):CD006850, 2010.

Richards BS, Vitale MG. Screening for idiopathic scoliosis in adolescents. An information statement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:195-198.

Tones M, Moss N, Polly DWJr. A review of quality of life and psychosocial issues in scoliosis. Spine. 2006;31:3027-3028.

Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Cheng JCY, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Lancet. 2008;371:1527-1536.

Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Spratt KF, et al. Health and function of patients with untreated idiopathic scoliosis. JAMA. 2003;289:559-567.

Wright JG, Donaldson S, Howard A, et al. Are surgeon’s preferences for instrumentation related to outcomes? A randomized clinical trial of two implants for idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2684-2693.

671.2 Congenital Scoliosis

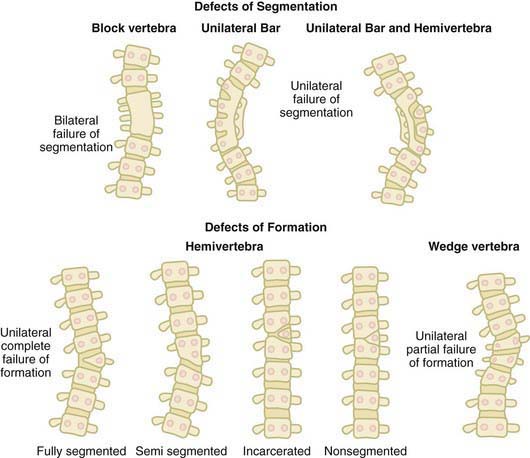

Congenital scoliosis results from abnormal growth and development of the vertebral column, likely due to intrauterine events at or about the 6th wk of gestation. There can be a partial or complete failure of formation (wedge vertebrae or hemivertebrae), a partial or complete failure of segmentation (unilateral unsegmented bars), or a combination of both (Fig. 671-5). One or more bony anomalies can occur in isolation or in combination.

Figure 671-5 The defects of segmentation and formation that can occur during spinal development.

(From McMaster MJ: Congenital scoliosis. In Weinstein SL, editor: The pediatric spine: principles and practice, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2001, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, p 163.)

Approximately 20-40% of patients have an intraspinal anomaly. Infants with cutaneous abnormalities overlying the spine might benefit from ultrasonography to rule out an occult spinal dysraphic condition. MRI is usually recommended during the course of treatment. Spinal dysraphism is the general term applied to such lesions (Chapters 585 and 598). Examples include diastematomyelia, split cord malformations, intraspinal lipomas (intradural or extradural), arachnoid cysts, teratomas, dermoid sinuses, fibrous bands, and tight filum terminale. Cutaneous findings that may be seen in patients with closed spinal dysraphism include hair patches, skin tags or dimples, sinuses, and hemangiomas. Most of these lesions become clinically evident through tethering of the spinal cord, the symptoms of which include back and/or leg pain, calf atrophy, progressive unilateral foot deformity (especially cavovarus), and problems with bowel or bladder function.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree