The Cardiovascular System:

Cardiac output and plasma volume decrease to prepregnant levels within a week. Loss of oedema can take up to 6 weeks. If transiently elevated, blood pressure is usually normal within 6 weeks.

The Urinary Tract:

The physiological dilatation of pregnancy reduces over 3 months and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) decreases.

The Blood:

Urea and electrolyte levels return to normal because of the reduction in GFR. In the absence of haemorrhage, haemoglobin and haematocrit rise with haemoconcentration. The white blood count falls. Platelets and clotting factors rise, predisposing to thrombosis.

General Postnatal Care

The mother and baby should not be separated, and privacy is important. Early mobilization is encouraged. Counselling and practical help with breastfeeding are often required. Uterine involution and the lochia, blood pressure, temperature, pulse and any perineal wound are checked daily. Careful fluid balance checks should prevent retention if a woman has had an epidural. Analgesics may be required for perineal pain, which is also helped by pelvic floor exercises. The full blood count may be checked before discharge, and iron is prescribed if appropriate, usually in conjunction with laxatives.

Ideally, the midwife or doctor who attended the delivery should visit the patient after delivery. The circumstances of the delivery should be discussed, particularly if there has been obstetric intervention, and the woman given the opportunity to ask questions about her labour. Discharge should be dependent on the mother’s wishes: some like to leave hospital within 6 h of delivery; others will need a few days in hospital. The GP should be alerted of any complications. Advice regarding contraception is given prior to discharge.

Psychiatric disease and suicide are now recognized as major contributors to maternal death. Most women have a psychiatric history but this is often not recorded. Psychiatric referral is recommended for women with such a history, and a postnatal plan including the GP is drawn up. Vigilance for evidence of depression is essential.

Lactation

Physiology

Lactation is dependent on prolactin and oxytocin. Prolactin from the anterior pituitary gland stimulates milk secretion. Levels of prolactin are high at birth, but it is the rapid decline in oestrogen and progesterone levels after birth that causes milk to be secreted, because prolactin is antagonized by oestrogen and progesterone. Oxytocin from the posterior pituitary stimulates ejection in response to nipple suckling, which also stimulates prolactin release and therefore more milk secretion. As much as 1000+ mL of milk per day can be produced, dependent on demand. Since oxytocin release is controlled via the hypothalamus, lactation can be inhibited by emotional or physical stress. Colostrum, a yellow fluid containing fat-laden cells, proteins (including immunoglobulin A) and minerals, is passed for the first 3 days, before the milk ‘comes in’.

Management

Women should be gently encouraged to breastfeed, when the baby is ready. Early feeding should be on demand. Correct positioning of the baby is vital: the baby’s lower lip should be planted below the nipple at the time that the mouth opens in preparation for receiving milk, so that the entire nipple is drawn into the mouth. This could largely prevent the main problems of insufficient milk, engorgement, mastitis and nipple trauma. A restful, comfortable environment is important, not least because oxytocin secretion, and therefore milk ejection, can be reduced by stress. Supplementation is unnecessary, although vitamin K should be given (BMJ 1996; 313: 199) to reduce the chances of haemorrhagic disease of the newborn.

Composition of Human Milk

| Protein | 1.0% |

| Carbohydrate | 7.0% |

| Fat | 4.0% |

| Minerals | 0.2% |

| Immunoglobulins | Mainly immunoglobulin A |

| Energy | 70 kcal/100 mL |

Advantages of Breastfeeding

Protection against infection in neonate

Bonding

Protection against cancers (mother)

Cannot give too much

Cost saving

Postnatal Contraception

Lactation not adequate alone, but important on global scale

Contraception is usually started 4–6 weeks after delivery

Combined contraceptive suppresses lactation and contraindicated if breastfeeding

Progesterone-only (pill or depot) safe with breastfeeding

Intrauterine device (IUD) safe: screen for infection first. Insert at end of third stage or at 6 weeks

Primary Postpartum Haemorrhage

Definition and Epidemiology

Primary primary postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is the loss of >500 mL blood <24 h of delivery (or >1000 mL after Caesarean). It occurs in about 10% of women and remains a major cause of maternal mortality.

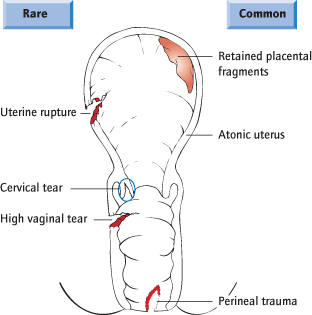

Aetiology (Fig. 33.2)

Retained placenta occurs in 2.5% of deliveries. Partial separation can cause blood to accumulate in the uterus, which will rise. Collapse may occur in the absence of external loss.

Uterine causes account for 80%. The uterus fails to contract properly, either because it is ‘atonic’ or because there is a retained placenta, or part of the placenta. Atony is more common with prolonged labour, with grand multiparity and with overdistension of the uterus (polyhydramnios and multiple pregnancy) and fibroids.

Vaginal causes account for about 20%. Bleeding from a perineal tear or episiotomy is obvious, but a high vaginal tear must be considered, particularly after an instrumental vaginal delivery.

Cervical tears are rare, but associated with precipitate labour and instrumental delivery.

Coagulopathy is rare. Congenital disorders, anticoagulant therapy or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) all cause PPH.

Risk Factors for Postpartum Haemorrhage (PPH)

Previous history

Previous Caesarean delivery

Coagulation defect or anticoagulant therapy

Instrumental or Caesarean delivery

Retained placenta

Antepartum haemorrhage

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree