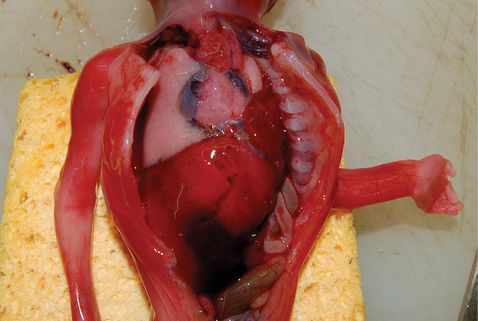

(a, b) Macroscopic photographs from perinatal autopsies demonstrating effects of maceration, such as skin slippage and bilateral talipes equinovarus (top) and congenital left-sided diaphragmatic hernia (bottom).

Histologic examination

Small tissue samples of major organs are examined under the microscope for cases in which the consent status allows this, since it is recognised that many conditions will only be apparent on histologic examination, despite an organ appearing as normal macroscopically. Tissue samples are processed into small paraffin wax blocks and tissue sections on glass slides, 3–5 microns in thickness, are stained for detailed characterization of the underlying disease process as required.

Ancillary investigations

Radiology

Whilst in some circumstances it had been standard practice to perform whole-body X-ray examinations, the diagnostic yield from this approach in the era of routine antenatal ultrasound screening is very low. However, if there are structural abnormalities, in particular skeletal abnormalities, detailed whole-body radiography is mandatory, and often provides the specific underlying diagnosis. Other imaging modalities that are now becoming more common include postmortem computed tomography (CT) and MRI, but these remain outside of routine clinical practice in most areas (Figure 29.2).

(a, b) Postmortem magnetic resonance images demonstrating enlarged hyperechogenic kidneys in a fetus with infantile polycystic kidney disease (top) and enlarged lungs with diaphragmatic eversion and massive ascites in a fetus with congenital high airway obstruction syndrome (CHAOS; bottom).

Other

A wide range of other ancillary investigations may be performed according to clinical indications, including microbiologic and virologic analyses, metabolic studies (blood and bile spots for acylcarnitine profiling by tandem mass spectrometry or enzyme assays using cultured fibroblasts) and cytogenetic and DNA analysis for genetic disease.

Retention of organs

Occasionally, it may be required to retain an organ temporarily for fixation and further examination. In the vast majority of cases, this will be known before the autopsy is conducted based on the clinical circumstances. Retention involves removal of the organ from the body and fixing in formalin, which hardens the tissues by crosslinking proteins, enabling more detailed macroscopic examination and high-quality histologic sections. Such temporary retention is usually only required for the brain, which is very friable and soft, and prone to disintegrate on handling, thus limiting the extent of the examination. Formalin fixation is also recommended for detailed examination of the heart in cases with suspected complex structural cardiac malformations. It should be noted that even if an organ is temporarily retained for formalin fixation and further examination, it is usually not retained indefinitely but is reunited with the body prior to release, although this may delay funeral arrangements. Should parents wish, retained organs can be returned at a later stage, usually via their designated undertakers, for subsequent burial or cremation or parents can request the hospital to dispose of the tissue in a lawful way. It is important that parents be informed that in certain cases, particularly terminations of pregnancy or deaths with suspected brain abnormality, fixation of the brain is likely to be required for adequate examination.

Disposal of retained tissue samples, including blocks and slides

The blocks and slides taken as part of the postmortem examination are usually kept as part of the medical record in order that they can be reviewed in the future as these tissue samples may also be valuable for medical education, audit, quality control and research. Parents have the option to consent to the use of tissue for research, which may help other families in the future, and surveys of bereaved parents have shown that the majority of parents are keen to participate in research[16].

Alternatively, parents can request that all samples are disposed of, either by the hospital or parents can make their own arrangements, usually via their designated undertaker. If parents choose either of these options, it is important that they understand that subsequent review and further diagnosis will not be possible. Note that any tissue samples taken during a coronial autopsy are under the authority of the HM Coroner and remain so until their investigation has ceased.

The limited/partial postmortem examination

Parents have the option to choose a limited or partial postmortem examination, which can take several forms: limited to external examination, with or without postmortem imaging but usually including placental examination, or restricted to a particular body region (such as the chest, abdomen or head) or specific organ (e.g., heart only). The information obtained by a limited postmortem examination may in certain circumstances provide sufficient information for definitive diagnosis and appropriate genetic counseling for future pregnancies, but due to potential limitations it is suggested that all cases of limited examination are discussed with pathologists prior to examination.

Limitations of postmortem examination

Despite the potential benefits, as outlined above, it is important that parents do not have unrealistic expectations. The examination may not answer their questions, and in a significant number of cases may not establish a cause of death, particularly for clinically unsuspected third trimester stillbirths. Conversely, as outlined above, although the postmortem examination may find “nothing new,” this too may be clinically helpful, providing reassurance to both clinicians and parents that nothing important had been overlooked during life.

The postmortem report

It is recommended that a final autopsy report, incorporating histologic findings and results of further investigations, is provided within 6 weeks (RCPath[17]). The report should both document the salient macroscopic and microscopic findings and results of ancillary investigations, and also contain a concise and appropriate clinicopathologic correlation and summary. Parents are entitled to a copy of the report, but it is recommended that the contents be discussed with them by their clinician prior to receipt, preferably in person, as some parents may find the technical language used in such reports insensitive or distressing.

Placental examination

Histopathologic examination of the placenta represents a subject in itself with detailed textbooks available for further reference regarding specific findings[18]. In this context, it should be recognized that examination of the placenta represents an important and intrinsic component of the perinatal autopsy. In some circumstances, for example, spontaneous miscarriage of an apparently normally formed fetus in the second trimester or an intrauterine death associated with pre-eclampsia, placental examination is likely to provide the most significant information of the entire autopsy process. In other circumstances, for example TOP for a fetus with an underlying structural cardiac abnormality, placental examination is likely to be noncontributory. For these reasons, it is difficult to determine the relative importance and contribution of placental examination since the majority of studies report on cases with a mixture of indications. However, one study specifically reporting on autopsy investigation in stillbirths reported that cases that also underwent placental examination were significantly less likely to remain unexplained, and in around half of all cases the findings of placenta investigation were included in the classification of the stillbirth[19]. Placental examination may reveal potentially recurrent disorders, such as massive perivillous fibrin deposition, chronic intervillositis or villitis of unknown etiology, and may confirm the presence of chorioamnionitis and funisitis, viral pathogens or fetal thrombotic vasculopathy, some of which may have implications for future siblings or pregnancies (Table 29.2). Moreover, targeted specialist investigations can be performed, such as vascular injection studies in complicated monochorionic twin placentas(Figure 29.3).

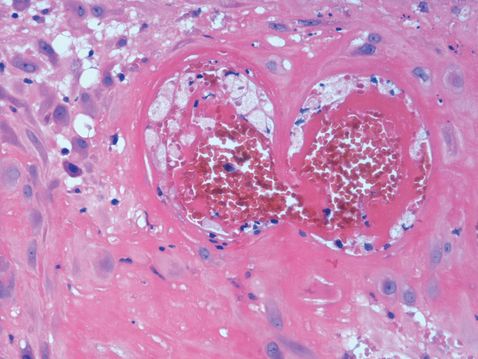

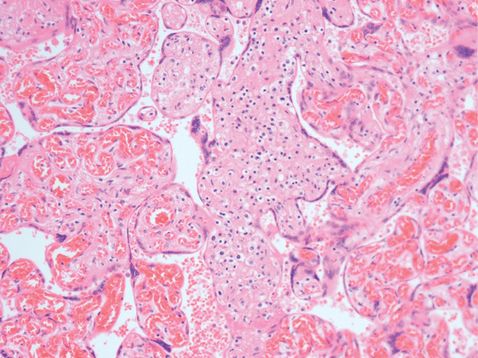

(a, b) Photomicrographs of histologic sections from perinatal autopsy cases demonstrating uteroplacental vascular disease with atherosis in a placental decidual section from a fetus with fetal growth restriction (top), and placenta showing villitis of unknown etiology (VUE; bottom).

| Pathological entity | Key features | Presumed mechanism/cause | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Massive perivillous fibrin deposition | Widespread fibrin surrounding villi and within the intervillous space | Haemodynamic or immune | 10–50% |

| Chronic histiocytic intervillositis | Accumulation of histiocytes in the intervillous space | Immune | 70% |

| Villitis of unknown etiology | Infiltration of villi by lymphocytes | Immune | 10–40% |

| Ascending genital tract infection | Neutrophilic infiltration of fetal membranes and/or placenta | Infection | 1–3-fold increase rate |

| Fetal thrombotic vasculopathy | Occlusive thrombi in fetoplacental vasculature | Thrombotic | Not known |

| Uteroplacental vascular disease | Vasculopathy affecting maternoplacental vessels with haemodynamic effects | Vasculopathic/immune | 20–30% |

| Distal villous immaturity | Poor formation of normal terminal villi | Developmental | Not known |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree