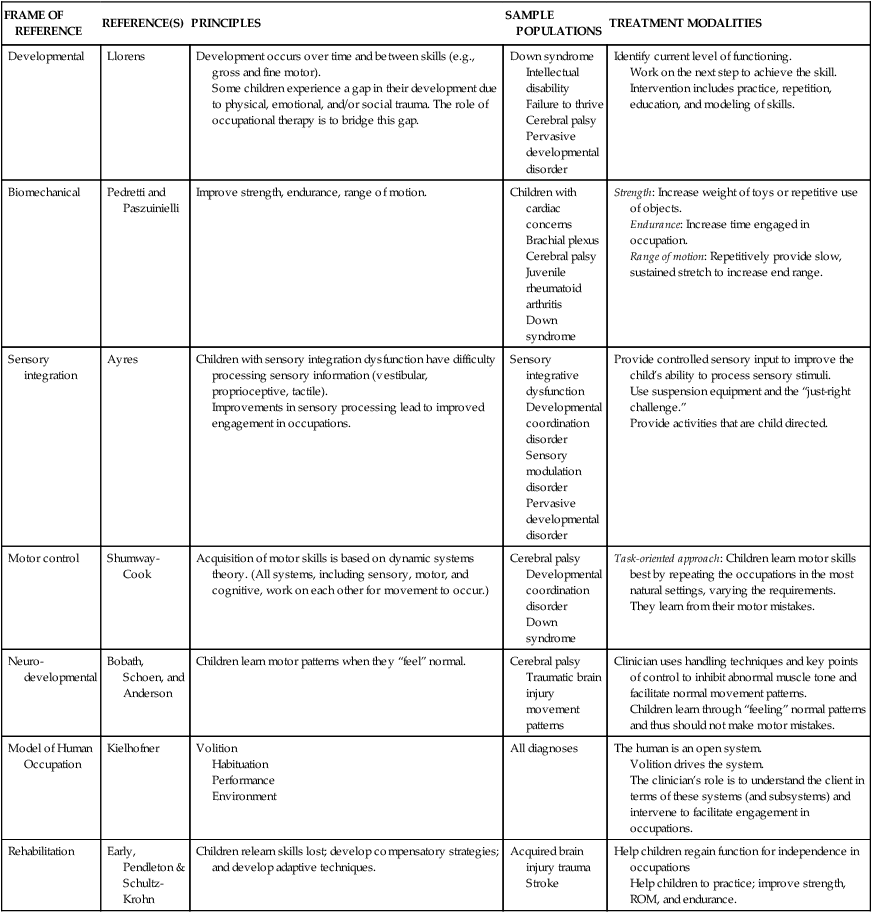

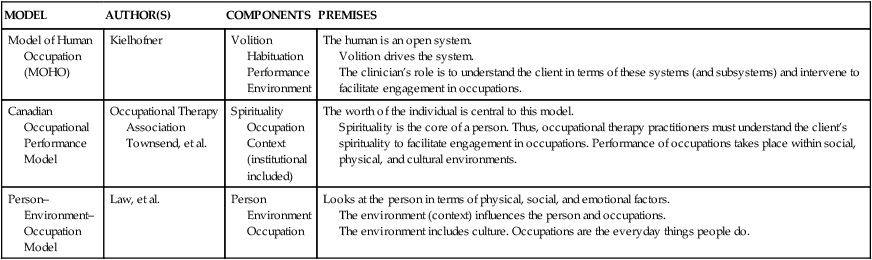

10 JEAN W. SOLOMON and JANE CLIFFORD O’BRIEN After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following: • Describe different pediatric frames of reference and practice models. • Explain the way in which assessment relates to program planning and intervention. • Differentiate among long-term goals, short-term objectives, and mini-objectives. • Apply activity analysis to intervention(s) with children and adolescents. • Define and describe therapeutic use of self. • Be aware of the importance of family-centered intervention and cultural diversity. • Discuss the preparation for and process of discharge planning or discontinuation of occupational therapy services. • Understand the top-down approach to intervention. • Identify and describe the tools of practice for working with children and adolescents. A model of practice (MOP) helps OT practitioners organize their thinking.13 For example, practitioners using the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) know that they will gather information about volition (e.g., the child’s or parents’ goals and priorities or occupational choices), habituation or routines (e.g., how the child spends the day), performance (e.g., the physical skills and abilities of the child), and environment (e.g., the physical layout of the home). Practitioners using the Person–Environment–Occupational-Performance model will organize their thinking into information about the child (e.g., the child’s physical abilities), the environment (e.g., where the child attends school) and occupational performance (e.g., how the child is performing his or her daily occupations). Other commonly used pediatric MOPs include Occupational Adaptation and the Canadian Occupational Performance Model. MOPs provide practitioners with a framework for thinking about and arranging their materials. They help practitioners focus on factors that influence functioning. MOPs are developed from OT theory and philosophy. As such, they fit with the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF) in their emphasis on occupation. See Table 10-1 for an overview of selected MOPs. TABLE 10-1 Data from Kielhofner G: A model of human occupation: Theory and application, ed 4, Baltimore, MD, 2008, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Law M, Cooper B, Stewart D, et al: The person-environment-occupation model: A transactive approach to occupational performance, Can J Occup Ther 63:9, 1996; Townsend E, Brintnell S, Staisey N: Developing guidelines for client-centered occupational therapy practice, Can J Occup Ther 57:69, 1990. According to the Standards of Practice for Occupational Therapy published by the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA), only occupational therapists may accept a referral for assessment.1 The OTA, if given a referral, is responsible for forwarding it to a supervising occupational therapist and educating “current and potential referral sources about the scope of occupational therapy services and the process of initiating occupational therapy referrals.”1 OTAs may acknowledge requests for services from any source. However, they do not accept and begin working on cases at their own professional discretion without the supervision and collaboration of the occupational therapist. Clients may first be introduced to OT through a screening. Screenings provide a general overview of a child’s functioning to determine if the child requires further evaluation. Both occupational therapists and OTAs can conduct such screenings. For example, an OTA may be hired to screen children in a well-baby clinic or an incoming kindergarten class to determine the need for additional evaluation before entering school. Once the OTA has identified the need for a more complete evaluation, the occupational therapist determines the specific evaluation or format to be used. The data gathered by the OTA are interpreted by the occupational therapist. An OTA “may contribute to this process under the supervision of a registered occupational therapist.”1 The evaluation is a critical part of the OT process. The occupational therapist is responsible for determining the type and scope of evaluation. An evaluation includes assessments of an individual’s areas of performance (e.g., activities of daily living [ADLs], instrumental ADLs [IADLs], work, education, play/leisure, social participation), client factors (e.g., neuromusculoskeletal, specific and global mental functions, body system), performance skills, performance patterns, contexts, and activity demands.2 According to AOTA, an entry-level OTA “assists with data collection and evaluation under the supervision of the occupational therapist.”3 An intermediate- or advanced-level OTA “administers standardized tests under the supervision of an occupational therapist after service competency has been established.”3 Although the OTA may participate in the evaluation process, the occupational therapist is responsible for interpreting the results and developing the intervention plan. The evaluation provides the OT practitioner with a picture of the child’s occupational needs as well as the child’s strengths and weaknesses. This occupational profile consists of a description of the level of performance at which the child functions. A child’s level of function may differ in relation to task, pattern, and context (Box 10-1). For example, a child may feed himself or herself independently at home after setup but be unable to do so at school in the time provided while sitting at the table because of the loud noises and confusion of the lunch room. The occupational therapist develops an intervention plan after the evaluation has been completed. The evaluation includes parental concerns, the client’s strengths and weaknesses, a statement of the client’s rehabilitation potential, long-term goals, and short-term objectives. The plan describes the type of media (i.e., specific types of materials) and modalities (i.e., intervention tools) that will be used and the frequency and duration of treatment. The plans for re-evaluation and discharge as well as the level of personnel providing the intervention are also included.1 Once practitioners have gained information by using an MOP, they must decide how to intervene. FORs are used to direct OT intervention. They inform practitioners on what to do and are based on theory, research, and clinical experience.13 FORs define the populations for which they are suitable, describe the continuum of function and dysfunction, provide assessment tools, describe treatment modalities and intervention techniques, define the role of the practitioner, and suggest outcome measures. FOR helps the OT practitioner identify problems and develop solutions. Common pediatric FORs in OT are MOHO, developmental, sensory integration, biomechanical, sensorimotor, motor control, and rehabilitation FORs. See Table 10-2 for an overview of FORs. MOHO is both a MOP and a FOR, since this model has numerous assessment tools and intervention strategies. As such, it provides an overall way of thinking and also meets the criteria for a FOR. See Chapter 25 for a description of MOHO. TABLE 10-2 Data from Ayres AJ: Sensory integration for the child, Los Angeles, 1979, Western Psychological Services; Bobath B: Sensorimotor development, NDT Newsletter 7:1, 1975; Early MB: Physical dysfunction practice skills for the occupational therapy assistant, ed 2, St. Louis, 2006, Mosby; Llorens LA: Application of a developmental theory for health and rehabilitation, Rockville, MD, 1976, American Occupational Therapy Association; Shultz-Krohn W, Pendleton H: Application of the occupational therapy framework to physical dysfunction. In Pendleton, H. & Shultz-Krohn, editors: Pedretti’s occupational therapy: Practice skills for physical dysfunction, ed 6, St Louis, 2006, Mosby; Schoen S, Anderson J: Neurodevelopmental treatment frame of reference. In Kramer P, Hinojosa J, editors: Frames of reference for pediatric occupational therapy, Baltimore, MD, 2009, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Shumway-Cook A, Woolacott M: Motor control: Issues and theories. In Shumway-Cook A, Woolacott M, editors: Motor control: Theory an practical applications, ed 2, Baltimore, MD, 2002, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. The following sections provide an overview and examples of specific FORs used with children.

The occupational therapy process

Models of practice

MODEL

AUTHOR(S)

COMPONENTS

PREMISES

Model of Human Occupation (MOHO)

Kielhofner

Volition

Habituation

Performance

Environment

The human is an open system.

Volition drives the system.

The clinician’s role is to understand the client in terms of these systems (and subsystems) and intervene to facilitate engagement in occupations.

Canadian Occupational Performance Model

Occupational Therapy Association Townsend, et al.

Spirituality

Occupation

Context (institutional included)

The worth of the individual is central to this model.

Spirituality is the core of a person. Thus, occupational therapy practitioners must understand the client’s spirituality to facilitate engagement in occupations. Performance of occupations takes place within social, physical, and cultural environments.

Person–Environment– Occupation Model

Law, et al.

Person

Environment

Occupation

Looks at the person in terms of physical, social, and emotional factors.

The environment (context) influences the person and occupations.

The environment includes culture. Occupations are the everyday things people do.

Referral, screening, and evaluation

Referral

Screening

Evaluation

Levels of performance

Intervention planning, goal setting, and treatment implementation

Intervention planning

Frames of reference

FRAME OF REFERENCE

REFERENCE(S)

PRINCIPLES

SAMPLE POPULATIONS

TREATMENT MODALITIES

Developmental

Llorens

Development occurs over time and between skills (e.g., gross and fine motor).

Some children experience a gap in their development due to physical, emotional, and/or social trauma. The role of occupational therapy is to bridge this gap.

Down syndrome

Intellectual disability

Failure to thrive

Cerebral palsy

Pervasive developmental disorder

Identify current level of functioning.

Work on the next step to achieve the skill. Intervention includes practice, repetition, education, and modeling of skills.

Biomechanical

Pedretti and Paszuinielli

Improve strength, endurance, range of motion.

Children with cardiac concerns

Brachial plexus

Cerebral palsy

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

Down syndrome

Strength: Increase weight of toys or repetitive use of objects.

Endurance: Increase time engaged in occupation.

Range of motion: Repetitively provide slow, sustained stretch to increase end range.

Sensory integration

Ayres

Children with sensory integration dysfunction have difficulty processing sensory information (vestibular, proprioceptive, tactile).

Improvements in sensory processing lead to improved engagement in occupations.

Sensory integrative dysfunction

Developmental coordination disorder

Sensory modulation disorder

Pervasive developmental disorder

Provide controlled sensory input to improve the child’s ability to process sensory stimuli.

Use suspension equipment and the “just-right challenge.”

Provide activities that are child directed.

Motor control

Shumway-Cook

Acquisition of motor skills is based on dynamic systems theory. (All systems, including sensory, motor, and cognitive, work on each other for movement to occur.)

Cerebral palsy

Developmental coordination disorder

Down syndrome

Task-oriented approach: Children learn motor skills best by repeating the occupations in the most natural settings, varying the requirements.

They learn from their motor mistakes.

Neuro- developmental

Bobath, Schoen, and Anderson

Children learn motor patterns when they “feel” normal.

Cerebral palsy

Traumatic brain injury movement patterns

Clinician uses handling techniques and key points of control to inhibit abnormal muscle tone and facilitate normal movement patterns.

Children learn through “feeling” normal patterns and thus should not make motor mistakes.

Model of Human Occupation

Kielhofner

Volition

Habituation

Performance

Environment

All diagnoses

The human is an open system.

Volition drives the system.

The clinician’s role is to understand the client in terms of these systems (and subsystems) and intervene to facilitate engagement in occupations.

Rehabilitation

Early, Pendleton & Schultz-Krohn

Children relearn skills lost; develop compensatory strategies; and develop adaptive techniques.

Acquired brain injury trauma

Stroke

Help children regain function for independence in occupations

Help children to practice; improve strength, ROM, and endurance.