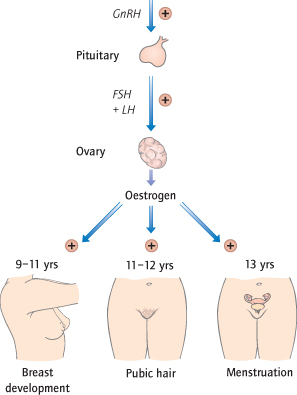

Fig. 2.2 Endocrine changes during puberty. FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GnRH, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone.

Oestrogen is responsible for the development of secondary sexual characteristics: the thelarche, or beginning of breast development, occurs first at 9–11 years; the adrenarche, or growth of pubic hair (also dependent on adrenal activity), starts at 11–12 years; the final stage is the menarche (Fig. 2.2). Menstruation may be irregular at first; as oestrogen secretion rises, it will become regular. Pregnancy is now possible. These changes are accompanied by the growth spurt, due to increased growth hormone release. By the age of 16 years, most growth has finished and the epiphyses fuse. The average age of the menarche is reducing.

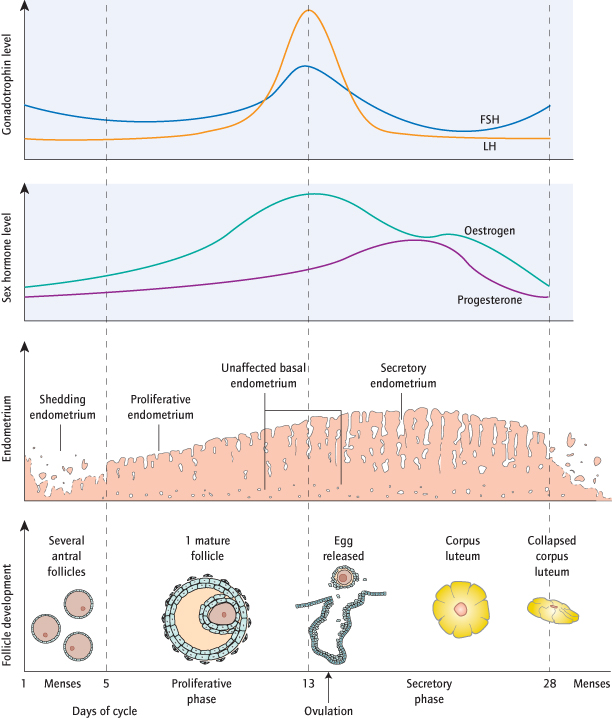

The Menstrual Cycle

The hormonal changes of the menstrual cycle cause ovulation and induce changes in the endometrium that prepare it for implantation should fertilization occur.

Days 1–4: Menstruation

At the start of the menstrual cycle (designated as the first day of menstruation) the endometrium is shed as its hormonal support is withdrawn. Myometrial contraction, which can be painful, also occurs.

Days 5–13: Proliferative Phase

Pulses of GnRH from the hypothalamus stimulate LH and FSH release which induce follicular growth. The follicles produce oestradiol and inhibin which suppress FSH secretion in a ‘negative feedback’, such that (normally) only one follicle and oocyte matures. As oestradiol levels continue to rise and reach their maximum, however, a ‘positive-feedback’ effect on the hypothalamus and pituitary causes LH levels to rise sharply: ovulation follows 36 hours after the LH surge. The oestradiol also causes the endometrium to re-form and become ‘proliferative’: it thickens as the stromal cells proliferate and the glands elongate.

Days 14–28: Luteal/Secretory Phase

The follicle from which the egg was released becomes the corpus luteum. This again produces oestradiol, but relatively more progesterone, levels of which peak around a week later (day 21 of a 28-day cycle). This induces ‘secretory’ changes in the endometrium, whereby the stromal cells enlarge, the glands swell and the blood supply increases. Towards the end of the luteal phase, the corpus luteum starts to fail if the egg is not fertilized, causing progesterone and oestrogen levels to fall. As its hormonal support is withdrawn, the endometrium breaks down, menstruation follows and the cycle restarts (Fig. 2.3). Continuous administration of exogenous progestogens maintains a secretory endometrium. This can be used to delay menstruation.

Normal Menstruation

Menarche <16 years

Menopause >45 years

Menstruation <8 days in length

Blood loss <80 mL

Cycle length 23–35 days

No intermenstrual bleeding (IMB)

Abnormal Menstruation and Definitions of Terms

| Menorrhagia | Heavy menstrual bleeding |

| Intermenstrual bleeding | Bleeding between periods |

| Irregular periods | Periods outside the range of 23–35 days with a variability of >7 days between the shortest and longest cycle |

| Postcoital bleeding | Bleeding after intercourse |

| Primary amenorrhoea | Periods never start |

| Secondary amenorrhoea | Periods stop for 6 months or more |

| Oligomenorrhoea | Infrequent periods (>every 35 days–6 months) |

| Postmenopausal bleeding | Bleeding 1 year after the menopause |

| Dysmenorrhoea | Painful periods |

| Premenstrual syndrome | Psychological and physical symptoms worse in the luteal phase |

Heavy Menstrual Bleeding (Menorrhagia)

Definition

Menorrhagia (heavy menstrual bleeding, HMB) is excessive bleeding in an otherwise normal menstrual cycle. This is subjective, as what constitutes heavy bleeding to one woman may be quite normal for another.

Clinical Definition:

This is excessive menstrual blood loss that interferes with the woman’s physical, emotional, social and material quality of life, and which can occur alone or in combination with other symptoms.

Objective Definition:

This is blood loss of >80 mL in an otherwise normal menstrual cycle. This value corresponds to the maximum amount that a woman on a normal diet can lose per cycle without becoming iron deficient. In practice, actual blood loss is rarely measured.

Epidemiology

One-third of women complain of heavy periods although most do not seek medical help.

Aetiology

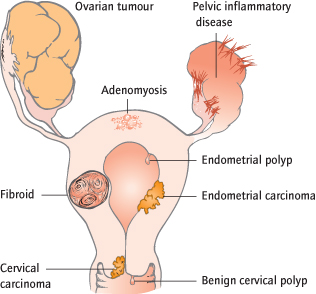

The majority of women with menorrhagia have no histological abnormality that can be implicated in its causation. Most women with regular cycles are ovulatory, and menorrhagia may result from subtle abnormalities of endometrial haemostasis or uterine prostaglandin levels. Uterine fibroids (approximately 30% of women with HMB) and polyps (approximately 10% of women with HMB) are the most common form of pathology found. Chronic pelvic infection, ovarian tumours, and endometrial and cervical malignancy (Fig. 2.4) usually cause irregular bleeding. Thyroid disease, haemostatic disorders, such as von Willebrand’s disease, and anticoagulant therapy are rare causes of menorrhagia. A coagulopathy may be suggested by a history of excessive bleeding after surgery/trauma or easy bruising.

Clinical Features

History:

This should assess both the amount and timing of the bleeding. A menstrual calendar is helpful. ‘Flooding’ and the passage of large clots indicate excessive loss. Any method of contraception should be ascertained.

Examination:

Anaemia is common. Pelvic signs are often absent. Irregular enlargement of the uterus suggests fibroids; tenderness with or without enlargement suggests adenomyosis. An ovarian mass or fibroids may be felt.

Investigations

To assess the effect of blood loss and fitness, the patient’s haemoglobin is checked.

To exclude systemic causes, coagulation and thyroid function are checked only if the history is suggestive of a problem.

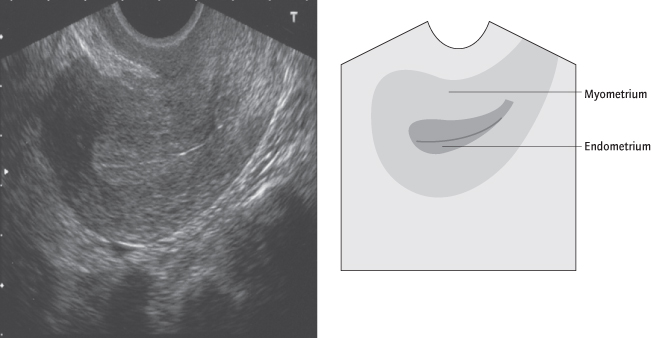

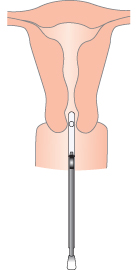

To exclude local organic causes, a transvaginal ultrasound of the pelvis is performed (Fig. 2.5). This will assess endometrial thickness, exclude a uterine fibroid or ovarian mass and detect larger intrauterine polyps. If the endometrial thickness is >10 mm or a polyp is suspected, or if the woman is over 40 years old with recent onset menorrhagia, or also has IMB, or has not responded to treatment, an endometrial biopsy (at hysteroscopy or with a Pipelle; Fig. 2.6) is performed to exclude endometrial malignancy or premalignancy [→ p.27]. Hysteroscopy allows, in addition to biopsy, an inspection of the uterine cavity, and therefore detection of polyps and submucous fibroids that could be resected. A dilatation and curettage (D&C) is not a treatment for menorrhagia.

Management

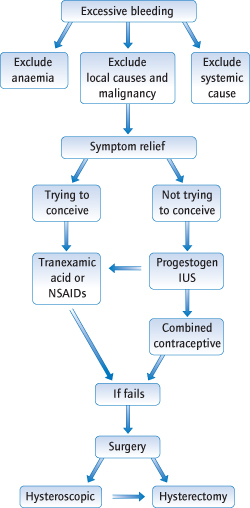

Treatment can be instigated once pathology has been excluded and depends on the woman’s contraceptive needs (Fig. 2.7). Thus, while intrauterine progestogens are very effective and recommended as a first line by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), this is not an option for a woman who wishes to conceive (http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG44/niceguidance/pdf/English).

Fig. 2.7 Management of heavy menstruation. IUS, intrauterine system; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Medical Treatment

First Line

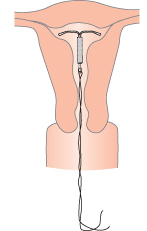

Intrauterine System (IUS):

This progestogen-impregnated intrauterine device (IUD; Fig. 2.8) is a ‘coil’ [→ p.103] that reduces menstrual flow by >90% with considerably fewer side effects than systemic progestogens. It is a highly effective alternative to both medical and surgical treatment of menorrhagia. It is a contraceptive and also provides the progestogen component of hormone replacement. It should be distinguished from copper IUDs which may increase menstrual loss.

Second Line

Antifibrinolytics (tranexamic acid) are taken during menstruation only. By reducing fibrinolytic activity this can reduce blood loss by about 50%. There are few side effects and in the UK it is available without prescription.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; e.g. mefanamic acid) inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, reducing blood loss in most women by about 30%. They are also useful for dysmenorrhoea. Side effects are similar to those of aspirin. Ibuprofen and aspirin are available without prescription.

The combined oral contraceptive usually induces lighter menstruation, but is less effective if pelvic pathology is present. Its role is more limited because its complications [→ p.100] are more common in older patients and it is these patients who have the most menstrual problems.

Third Line

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree