Estimation of Gestational Age

From last menstrual period (LMP), allowing for cycle length

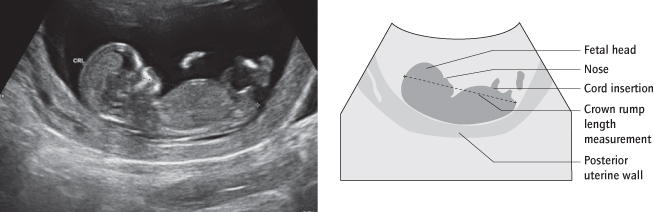

Ultrasound scan:

1 Measurement of crown–rump length between 9 and 14 weeks (Fig. 16.2)

2 Head circumference between 14 and 20 weeks if no early scan and LMP unknown.

Measurements to calculate gestational age are of little use beyond 20 weeks.

Complications of Pregnancy:

Has there been any bleeding or hypertension, diabetes, anaemia, urine infections, concerns about fetal growth, or other problems? Ask if she has been admitted to hospital in the pregnancy?

Tests:

What tests have been performed (e.g. ultrasound scans, blood tests, prenatal diagnostic tests [→ p.153]).

Past Obstetric History

Take details of past pregnancies in chronological order. Ask what was the mode and gestation of delivery and, if operative, why. Ask the birth weight and sex of the baby, and if the mother or the baby had any complications.

Parity:

This is the number of times a woman has delivered potentially viable babies (in UK law this is defined as beyond 24 completed weeks). A woman who has had three term pregnancies is ‘para 3’, even if she is now in her fourth pregnancy. A suffix denotes the number of pregnancies that have miscarried (or been terminated) before 24 weeks; for example, if the same woman had had two prior miscarriages at 12 weeks, she would be described as ‘para 3 + 2’. A nulliparous woman has never delivered a potentially live baby, although she may have had miscarriages or abortions; a multiparous woman has delivered at least one baby at 24 completed weeks or more.

Gravidity:

This describes the number of times a woman has been pregnant. The woman above would be gravida 6, encompassing her three term deliveries, two miscarriages and the present pregnancy. The use of the term gravid is less descriptive and is best avoided.

Nulliparity and Multiparity

| Nulliparous: | Has delivered no live/potentially live babies |

| Multiparous: | Has delivered live/potentially live (>24 week) babies |

Other History

Past Gynaecological History:

This should be brief. Ask the date of the last cervical smear and if she has been treated for an abnormal smear. Ask about prior contraception and any difficulty in conceiving.

Past Medical History:

Ask about operations, however distant. Ask about heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, psychiatric disease, epilepsy and other chronic illnesses. Ask ‘have you ever been in hospital?’

Systems Review:

Ask the usual cardiovascular, respiratory, abdominal and neurological questions.

Drugs:

What drugs was she taking at conception? What was she taking before (she might have stopped a drug) and what now?

Family History:

Is there a family history of twins, of diabetes, hypertension, pre-eclampsia, autoimmune disease, venous thromboembolic disease or thrombophilia, or of any inherited disorder?

Personal/Social History:

Does she smoke or drink alcohol? If either, how much? Ask, sensitively, about other drugs. Is she in a stable relationship and is there social support? Remember that domestic abuse is very common.

Allergies:

Ask specifically about penicillin and latex.

Venous Thromboembolic (VTE) Risk:

consider her risk factors for this major cause of maternal mortality. A risk assessment form is now routinely used in pregnancy [→ p.192].

Other Questions

Now Ask:

‘Is there anything else you think I ought to know?’ The patient may be knowledgeable about her condition and this gives her the opportunity to help you if you have not discovered all the important facts.

Presenting the History

Start by summing up the important points, including important facts about any presenting complaint:

This is … aged … , who is … weeks into her … pregnancy and has been admitted to hospital because of …

Example: This is Mrs X, aged 30 years, who is 38 weeks into her previously uncomplicated second pregnancy and has been admitted to hospital because of a painless antepartum haemorrhage.

N.B. You have demonstrated your understanding by mentioning the absence of pain, an important factor in the differential diagnosis of antepartum haemorrhage.

Now go through the history in some detail.

Then sum up again, in one sentence, including any important findings in the history.

Why Routinely Palpate the Abdomen?

| <24 weeks: | To check dates, twins |

| >24 weeks: | To assess well-being by assessing size and liquor |

| >36 weeks: | To check lie, presentation and engagement |

The Obstetric Examination

General Examination

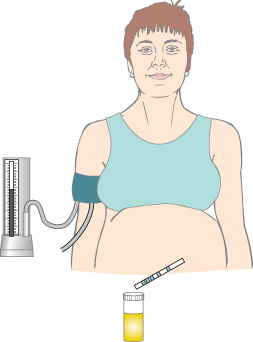

General appearance, temperature, oedema and possible anaemia are assessed. At the booking visit, the weight, height (calculate and record the BMI), chest, breasts, cardiovascular system and legs are also examined. The blood pressure and urinalysis tests should be performed together so that they are not forgotten (Fig. 16.3). The patient lies comfortably with her back semi-prone at 45°. Diastolic blood pressure is recorded as Korotkoff V (when the sound disappears). If the blood pressure is raised or if there is proteinuria, examine elsewhere also [→ p.176] (e.g. for epigastric tenderness).

Patients and Actors in Exams

Make eye contact with the patient

Ensure you know her name

Smile and talk to her

Make sure she is comfortable, e.g. neck supported

Be gentle and watch her face when you examine

Her assessment is as important as the examiner’s

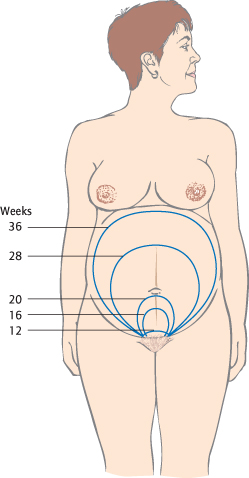

Abdominal Examination

The patient should now lie semi-prone, discreetly exposed from just below the breasts to the symphysis pubis. In later pregnancy, the semi-prone position or left lateral tilt will avoid aortocaval compression [→ p.246]. Talk to her, make eye contact and be gentle. The uterus is normally palpable abdominally at 12–14 weeks. By 20 weeks the fundus is usually at the level of the umbilicus. Before 20 weeks a uterus that is larger than expected could be due to incorrect dates, a full bladder, multiple pregnancy, uterine fibroids or a pelvic mass.

Inspection

Look at the size of the pregnant uterus and look for striae, the linea nigra and scars, particularly in the suprapubic area (Fig. 16.4). Fetal movements are often visible in later pregnancy.

Palpation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree