Intrauterine Growth Restriction (IUGR)

This describes fetuses that have failed to reach their own ‘growth potential’. Their growth in utero is slowed: many end up ‘small for dates’ (SFD), but some do not: many stillbirths or fetuses distressed in labour are of apparently ‘normal’ weight. If a fetus was genetically determined to be 4 kg at term and delivers at term weighing 3 kg, its growth has been restricted, and it may have placental dysfunction (Fig. 25.2) (www.gestation.net). Similarly, an ill, malnourished, tall adult may weigh more than a healthy shorter one. This means that whilst most IUGR babies are SFD, a proportion do not appear to be.

Fetal Distress

This refers to an acute situation, such as hypoxia, that may result in fetal damage or death if it is not reversed, or if the fetus delivered urgently. As such it is usually used in labour (see Chapter 29). Nevertheless, most babies that subsequently develop cerebral palsy were not born hypoxic.

Fetal Compromise

This describes a chronic situation and should be defined as when conditions for the normal growth and neurological development are not optimal. Most identifiable causes involve poor nutrient transfer through the placenta, often called ‘placental dysfunction’. Commonly there is intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), but this may also be absent (e.g. maternal diabetes or prolonged pregnancy).

Fetal Surveillance

Aims of Fetal Surveillance

1 Identify the ‘high-risk’ pregnancy using history or events during pregnancy, or using specific investigations.

2 Monitor the fetus for growth and well-being. The methods used will vary according to pregnancy risk and events during the pregnancy.

3 Intervene (usually expedite delivery) at an appropriate time, balancing the risks of in utero compromise against those of intervention and prematurity. The latter is itself a major cause of mortality and morbidity.

Problems with Fetal Surveillance

All methods of surveillance have a false positive rate (i.e. they can be over-interpreted). Whilst they may identify problems, they do not necessarily solve them and prevent adverse outcomes. In addition, they ‘medicalize’ pregnancy by concentrating on the abnormal, and they are expensive. For these reasons, identification of pregnancy risk is important.

Identification of the High-Risk Pregnancy

| Prepregnancy: | Poor past obstetric history or very small baby |

| Maternal disease | |

| Assisted conception | |

| Extremes of reproductive age | |

| Heavy smoking or drug abuse | |

| During pregnancy: | Hypertension/ proteinuria |

| Vaginal bleeding | |

| Small for dates (SFD) baby | |

| Prolonged pregnancy | |

| Multiple pregnancy | |

| Available investigations: | Cervical scan at 23 weeks [→ p.203] |

| Uterine artery Doppler | |

| Maternal blood tests, e.g. PAPP-A |

Identification of Pregnancy Risk

Prepregnancy Risks

History:

The traditional methods have centred on history: the mother’s age, her previous medical history and obstetric history (see box). Unfortunately, most women who develop pregnancy complications such as IUGR do not have any such risk factors: i.e. the use of history as a screening test is not sensitive. Further, taking all minor risk factors such as age >35 years will mean that many women who would have had normal pregnancy outcomes are considered high risk, i.e. the use of history as a screening test is not specific.

Early Pregnancy

Blood Tests:

Pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) is a placental hormone, the maternal level of which is reduced in the first trimester with chromosomal abnormalities. It is therefore used in screening for Down’s syndrome. It is now known that a low level constitutes a high risk for IUGR, placental abruption and consequent stillbirth (JAMA 2004; 292: 2249).

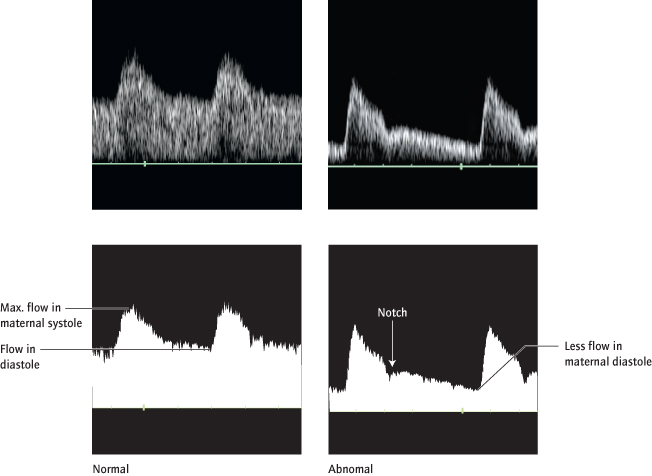

Maternal Uterine Artery Doppler:

(Fig. 25.3) The uterine circulation normally develops a very low resistance in normal pregnancy. Abnormal waveforms at 23 weeks, suggesting failure of development of a low resistance circulation, identify 75% of pregnancies at risk of adverse neonatal outcomes in the early third trimester, particularly early pre-eclampsia, IUGR or placental abruption. This test is less predictive of later problems. Uterine artery Doppler can also be performed in the first trimester but is less sensitive than at 23 weeks.

These tests are not universally used. However, they are potentially invaluable, particularly in combination:

Integrated Screening for Pregnancy Risk:

Using integration of (the above) different independent risk factors as in screening for chromosomal abnormalities [→ p.153] will increase the accuracy of screening. In this way, factors in the history and investigations can be used to identify more high-risk women (with a lower false-positive rate). This is currently under evaluation but is likely to enable more appropriate targeting of hospital-based and high-risk antenatal care.

Later Pregnancy

Pregnancy Events:

The occurrence of pre-eclampsia or vaginal bleeding, or if routine abdominal palpation suggests an SFD fetus, more close examination is required and the risk level will change.

Methods of Fetal Surveillance

Routine Pregnancy Care

The tests outlined below are not routine in low risk pregnancy. Here, the cornerstone of the identification of the small or compromised fetus is serial measurement of the symphysis fundal height and other aspects of antenatal visits [→ p.149].

Ultrasound Assessment of Fetal Growth

What It Is:

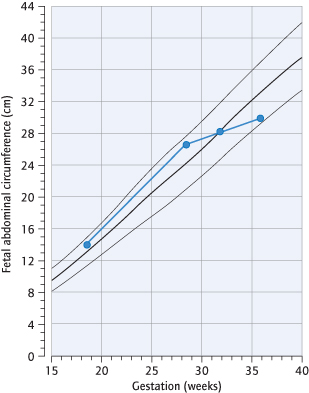

Ultrasound scan is used to measure fetal size after the first trimester, particularly the abdominal and head circumferences (Fig. 25.4). These changes are recorded on centile charts (Fig. 25.5). Three factors help to differentiate between the healthy small fetus and the ‘growth-restricted’ fetus:

1 The rate of growth can be determined by previous scans, or a later examination, at least 2 weeks apart.

2 The pattern of ‘smallness’ may help: the fetal abdomen will often stop enlarging before the head, which is ‘spared’. The result is a ‘thin’ fetus or ‘asymmetrical’ growth restriction.

3 Allowance for constitutional non-pathological determinants of fetal growth enables ‘customization’ of individual fetal growth, assessing actual growth according to expected growth.