The Floppy Infant and the Late Walker

Richard S. K. Young

The pediatrician may occasionally discover that an infant has poor head or truncal tone, and laxity in the arms and legs. This condition is commonly referred to as “The Floppy Infant.” The child who is not yet walking independently at 18 months of life is termed a “late walker.” Although these terms are not specific, they are useful as interim diagnostic labels until a more conclusive diagnosis is reached. During the past decade, major strides have been made in the understanding of the pathophysiology of these conditions.

HISTORY

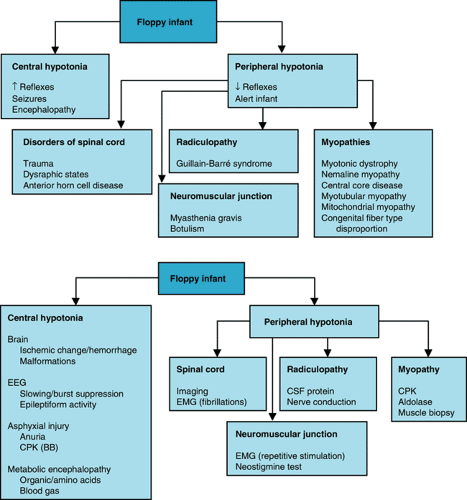

In the diagnosis of neurologic disease, the patient’s history furnishes clues to the nature of the disorder, and the physical examination and laboratory tests provide confirmation. When the history of an infant with hypotonia is taken, information regarding any family history of neuromuscular disease, the quality of the fetal movements, and the presence of hydramnios should be obtained. The temporal sequence of the disorder is of particular importance (When did it start? Is it progressive or static? Is the child worse today than he or she was one month ago?). The child’s pattern of growth and his or her ability to feed should be elicited. Figure 37.1 presents algorithms for general diagnostic approaches to hypotonia.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A general physical examination of any infant with suspected neurologic disease is essential to rule out motor delays caused by systemic disease. It should be determined whether congestive heart failure (dyspnea, edema, organomegaly) may be responsible for weakness or fatigue. The child should be examined for dysmorphic features (suggestive of a chromosomal abnormality) and for signs of endocrinopathy or metabolic disorder (umbilical hernia, dull cry, abnormal hair texture).

Weakness typically manifests in the neck, resulting in poor head control. Weakness in the proximal large muscles of the pectoral and pelvic girdle may result in delay in walking in the older child. The muscles should be inspected for bulk, atrophy, fasciculations, and symmetry. The presence of fasciculations in the tongue muscle is evidence of denervation. The muscle stretch reflexes should be tested, and it should be determined whether sensation is intact. Weakness in the facial or bulbar musculature is prominent in several disorders (myotonic dystrophy, myasthenia gravis, Möbius syndrome).

NEUROLOGIC EVALUATION

Based on the results of the history and physical examination, the physician first should determine whether a problem exists or whether a child simply is at the lower limits of normal. If a neuromuscular disorder is suspected, it should be decided whether the lesion is central (spasticity correlates with upper motor neuron involvement) or peripheral (hyporeflexia correlates with an interruption of the lower motor neuron arc). The pediatrician should think systematically about each element of the motor system, beginning with the cerebral cortex, proceeding to the spinal cord, the anterior horn cells, the peripheral nerves, and the neuromuscular junction (motor end plate) to the muscle fiber. The child’s gait should be carefully examined. Toe-walking or hemiplegia may be signs of corticospinal tract disease. An ataxic gait may suggest cerebellar dysfunction, whereas an athetotic gait may implicate the basal ganglia.

NEURODIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Cerebral MRI, both imaging and spectroscopy, is a useful method of result for the detection of cerebral causes of the floppy infant. Electromyography often is a helpful adjunct in the diagnosis of Werdnig-Hoffman disease, polyneuropathy, and botulism. Infants with congenital myopathies may require examination of muscle tissue for histologic and biochemical abnormalities.

CAUSES

Central Nervous System Injuries or Malformations

Cerebral injuries or malformations account for approximately one-half of floppy infants (central hypotonia). Cerebral conditions that may result in a floppy infant include hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, intracranial infection, cerebral hemorrhage, cerebral trauma, metabolic disorders, cerebral malformations, and chromosomal malformations. Children with these disorders may have seizures or other signs of cerebrocortical dysfunction. Central, as opposed to peripheral, causes of weakness result in spasticity, with ankle clonus, crossed adductor reflex, Babinski sign, and fisting. Strabismus also may suggest central nervous system dysfunction that causes floppiness in an infant.

Spinal Cord Disease

The most common causes of spinal cord disease producing a floppy infant are trauma, dysraphism (myelomeningocele), and degeneration of the anterior horn cells. Cervical spinal cord injury may result from tearing or shearing of the spinal cord during delivery of a large infant. Tumors, infections, or demyelination of the spinal cord are less common. Seesaw respirations

are a sign of diaphragmatic breathing and indicate that the lesion is above the C4 level (emergence of the phrenic nerve). Widespread degeneration of anterior horn cells also may produce diaphragmatic breathing.

are a sign of diaphragmatic breathing and indicate that the lesion is above the C4 level (emergence of the phrenic nerve). Widespread degeneration of anterior horn cells also may produce diaphragmatic breathing.

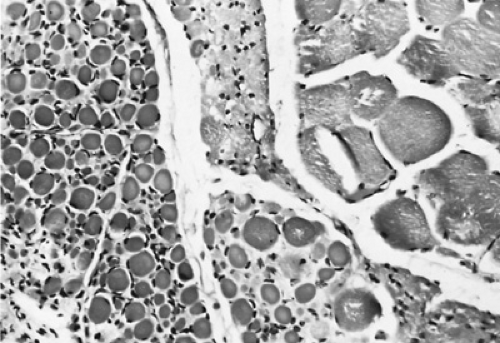

The selective loss of the anterior horn cells may occur during fetal life, in infancy, or during early childhood. If the onset of paralysis occurs in utero, the infant may exhibit widespread contractures (arthrogryposis multiplex congenita). One-half of patients with arthrogryposis have either neurogenic or myopathic etiologies, while the other half remains undiagnosed. Virtually all other sensory or association neurons in the nervous system are spared, leaving consciousness unimpaired. The diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of group atrophy on muscle biopsy samples (Fig. 37.2) and by electromyography (EMG). Anterior horn cell disorders (including spinal muscular atrophy) are among the more common autosomal recessive disorders, occurring in 1:10,000 live births, with a carrier frequency of 1 in 50; this disorder maps to a locus at 5q11.2. Anterior horn cell disease (Werdnig-Hoffmann syndrome) accounted for 15 of 41 floppy infants in the study of David and Jones (1994). Genetic testing and counselling for anterior horn disease should be considered in all children with this condition.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree