Chapter 415 The Fetal to Neonatal Circulatory Transition

415.1 The Fetal Circulation

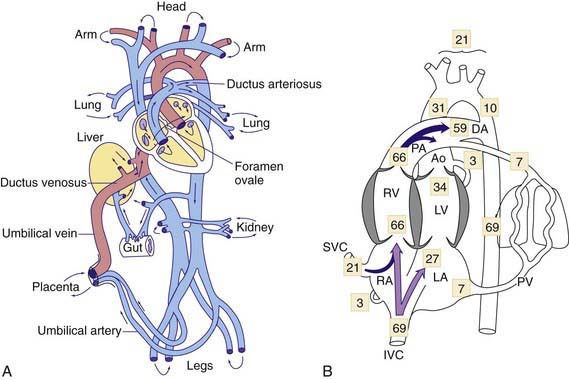

The human fetal circulation and its adjustments after birth are similar to those of other large mammals, although rates of maturation differ. In the fetal circulation, the right and left ventricles exist in a parallel circuit, as opposed to the series circuit of a newborn or adult (see ![]() Fig. 415-1A on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com). In the fetus, the placenta provides for gas and metabolite exchange. Since the lungs do not provide gas exchange, the pulmonary vessels are vasoconstricted, diverting blood away from the pulmonary circulation. Three cardiovascular structures unique to the fetus are important for maintaining this parallel circulation: the ductus venosus, foramen ovale, and ductus arteriosus.

Fig. 415-1A on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com). In the fetus, the placenta provides for gas and metabolite exchange. Since the lungs do not provide gas exchange, the pulmonary vessels are vasoconstricted, diverting blood away from the pulmonary circulation. Three cardiovascular structures unique to the fetus are important for maintaining this parallel circulation: the ductus venosus, foramen ovale, and ductus arteriosus.

The placenta is not as efficient an oxygen exchange organ as the lungs, so that umbilical venous PO2 (the highest level of oxygen provided to the fetus) is only about 30-35 mm Hg. Approximately 50% of the umbilical venous blood enters the hepatic circulation, whereas the rest bypasses the liver and joins the inferior vena cava via the ductus venosus, where it partially mixes with poorly oxygenated inferior vena cava blood derived from the lower part of the fetal body. This combined lower body plus umbilical venous blood flow (PO2 of ≈26-28 mm Hg) enters the right atrium and is preferentially directed by a flap of tissue at the right atrial–inferior vena caval junction, the eustachian valve, across the foramen ovale to the left atrium (see Fig. 415-1B). This is the major source of left ventricular blood flow, since pulmonary venous return is minimal. Left ventricular blood is then ejected into the ascending aorta where it supplies predominantly the fetal upper body and brain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree