Source: WHO classification of tumours of the uterine corpus. In: Kurman RJ, Carcangiu ML, Herrington CS, et al., eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive Organs, 4th ed. Lyons, France: IARC Press; 2014:122, with permission.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

KEY POINTS

- Leiomyosarcomas are the most common uterine mesenchymal tumor when excluding carcinosarcomas.

- Uterine sarcomas are more common in African American women.

- Prior radiotherapy is a risk factor for carcinosarcoma and undifferentiated sarcoma.

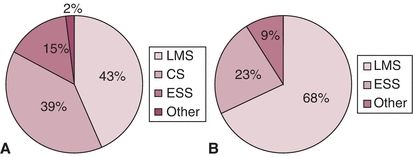

The most common uterine sarcomas are carcinosarcomas and leiomyosarcomas. When carcinosarcomas are excluded, leiomyosarcomas represent more than two thirds of uterine mesenchymal tumors (Fig. 9.1). Endometrial stromal sarcomas (ESS) account for 25% of true uterine sarcomas and are presently by definition “low grade.” The preferred current terminology for previously “high-grade” ESS is undifferentiated uterine sarcoma. Patients with carcinosarcomas and adenosarcomas tend to be older at the time of diagnosis compared to those with leiomyosarcomas and ESS.

Figure 9.1 Histologic distribution of uterine sarcomas in series with at least 100 cases including carcinosarcomas (A) and excluding carcinosarcomas (B). (ESS, endometrial stromal sarcoma; CS, carcinosarcoma; LMS, leiomyosarcoma; AS, adenosarcoma.) Source: From Park J, Kim D, Suh D, et al. Prognostic factors and treatment outcomes of patients with uterine sarcoma: Analysis of 127 patients at a single institution, 1989–2007. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134:1277–1287; Koivisto-Korander R, Butzow R, Koivisto A, et al. Clinical outcome and prognostic factors in 100 cases of uterine sarcoma: Experience in Helsinki University Central Hospital 1990–2001. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:74–81; Kahanpaa K, Wahlstrom T, Grohn P, et al. Sarcomas of the uterus: A clinicopathologic study of 119 patients. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:417–424; George M, Pejovic MH, Kramar A. Uterine sarcomas: Prognostic factors and treatment modalities—Study on 209 patients. Gynecol Oncol. 1986;24:58–67; Olah KS, Gee H, Blunt S, et al. Retrospective analysis of 318 cases of uterine sarcoma. Eur J Cancer. 1991;27:1095–1099; Pautier P, Genestie C, Rey A, et al. Analysis of clinicopathologic prognostic factors for 157 uterine sarcomas and evaluation of grading score validated for soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 2000;88:1425–1431; Abeler VM, Royne O, Thorensen S, et al. Uterine sarcomas in Norway. A histopathological and prognostic survey of a total population from 1970 to 2000 including 419 patients. Histopathology. 2009;54:355–364, with permission.

Women with carcinosarcomas are more likely to be of African American descent than those with endometrial adenocarcinomas. The age-adjusted incidence of uterine sarcomas in African American women is approximately twice that of Caucasian women. Carcinosarcomas and leiomyosarcomas constitute about 4% and 1.5% of all uterine malignancies, respectively. The risk profile of carcinosarcomas closely parallels that of endometrial adenocarcinomas with regard to obesity, diabetes, anovulation, and low parity, providing additional support that they be regarded as “metaplastic” endometrial carcinomas instead of true sarcomas.

Possible risk factors for uterine sarcoma are prior radiation exposure, hormone exposure, tamoxifen use, and hereditary predisposition. Prior exposure to pelvic radiotherapy is thought to increase the risk of developing subsequent carcinosarcoma and undifferentiated sarcoma. Carcinosarcomas in previously irradiated patients also tend to present in advanced stage, perhaps because radiotherapy is often associated with cervical stenosis and, thus, no telltale uterine bleeding. The association with hormone exposure is strongest for leiomyosarcoma. There may be a small risk of uterine sarcomas associated with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer and hereditary retinoblastoma.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Vaginal bleeding is the most common presenting symptom in women with uterine sarcomas in general and is nearly universal in those with carcinosarcomas. Vaginal bleeding occurs in as few as 40% of women with leiomyosarcomas, however. A typical presentation of carcinosarcoma is vaginal bleeding associated with a protuberant, fleshy mass from the cervix. These neoplasms arise in the endometrial lining but often grow in an exophytic pattern within the endometrial cavity (Fig. 9.2).

Figure 9.2 Exophytic pattern of growth in carcinosarcoma.

Uterine enlargement and a presumptive diagnosis of uterine leiomyomata are nearly universal findings in patients with leiomyosarcoma. The incidence of leiomyosarcoma in all patients with the clinical picture of myomas is less than 1% but increases with age to slightly over 1% in the sixth decade of life.

DIAGNOSIS AND EVALUATION

Vaginal bleeding in a postmenopausal female should be evaluated with endometrial sampling and possibly transvaginal ultrasound. Whereas the diagnosis of carcinosarcoma is confirmed, or at least suggested, at the time of endometrial biopsy or curettage, leiomyosarcomas are rarely diagnosed before hysterectomy.

Laparoscopy has become a standard and preferred approach in the management of benign and malignant gynecologic conditions. Morcellation is often not done in women with carcinosarcoma because they are often older with a preoperative diagnosis. Morcellation of uterine leiomyosarcoma is associated with a worsened outcome. The 5-year overall survival (OS) was 46% after morcellation compared to 73% in those not morcellated (p = 0.04). There is literature to support that the combination of serum lactate dehydrogenase and dynamic MRI may help to evaluate uterine lesions for leiomyosarcoma. Recent controversy regarding the use of morcellation has heightened the awareness of these issues and led to cautionary statements from the government and professional societies.

STAGING AND PROGNOSIS

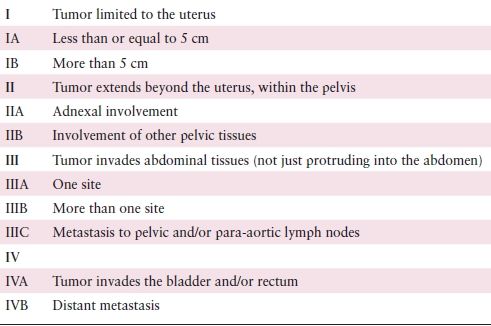

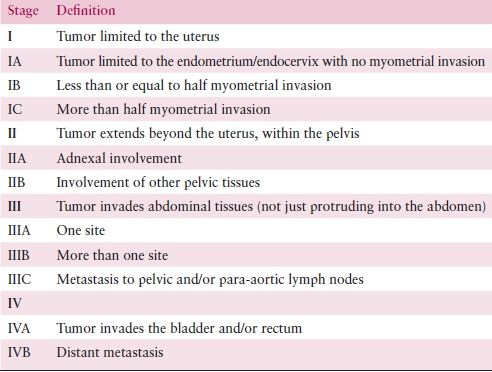

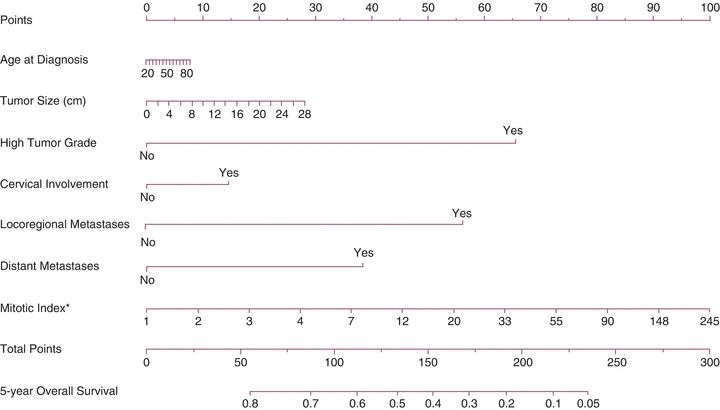

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) devised a sarcoma-specific staging system in 2009 for leiomyosarcoma, ESS, and adenosarcoma (Tables 9.2 and 9.3). Carcinosarcomas are staged using the system for endometrial carcinoma. A nomogram is also available online at http://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/adult/endometrial-other-uterine/leiomyosarcoma/prediction-tools (Fig. 9.3).

Table 9.2 The 2009 FIGO Staging System for Uterine Leiomyosarcomas and ESS

Source: From D’Angelo E, Prat J. Uterine sarcomas: A review. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:131–139, with permission.

Table 9.3 The 2009 FIGO Staging System for Uterine Adenosarcomas

Source: From D’Angelo E, Prat J. Uterine sarcomas: A review. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:131–139, with permission.

Figure 9.3 Nomogram for 5-year OS for uterine leiomyosarcoma. This is the uterine leiomyosarcoma nomogram for 5-year OS. The mitotic index (asterisk) was modeled using log transformation; for display purposes, values were converted back to original scale (exponential; concordance probability [CP], 0.671; bootstrap-validated CP, 0.651). Source: Zivanovic O, Jacks LM, Iasonos A, et al. A nomogram to predict postresection 5-year overall survival for patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma. Cancer. 2012;118:660–669.

Staging systems and nomograms have limited prognostic capabilities because they rely on anatomic, clinical, and pathologic criteria that have not been consistently associated with outcome. A better molecular understanding is urgently needed and may provide greater prognostication. Expression patterns of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), β-catenin, cyclooxygenase-2, and bcl-2 have all been reported to be associated with survival in leiomyosarcoma.

PATHOLOGY

Malignant mesenchymal tumors can be classified into pure mesenchymal tumors and tumors with a mixed epithelial and mesenchymal component. In the first group, the most common is leiomyosarcoma, followed by endometrial stromal sarcoma, and, rarely, others including rhabdomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, angiosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, and alveolar soft part sarcoma. Mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumors include carcinosarcoma and adenosarcoma. In addition, there are three rare mesenchymal tumors occurring in the uterus: uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord tumors, perivascular epithelioid cell tumors, and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor.

Leiomyosarcoma and Other Smooth Muscle Tumors

Leiomyosarcomas are malignant smooth muscle tumors that usually arise de novo. Recent studies have shown that some tumors display areas with benign morphology, suggesting some progression from leiomyoma to leiomyosarcoma; however, clonality studies only support this progression in a small percentage of cases. Microscopically, most leiomyosarcomas are overtly malignant and have hypercellularity, coagulative tumor cell necrosis, abundant mitoses (more than 10/10 hpf), atypical mitoses, marked cytologic atypia, and infiltrative borders. The three most important criteria are coagulative tumor cell necrosis, high mitotic rate, and significant cytologic atypia.

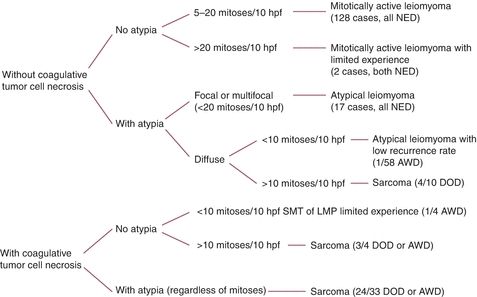

Some smooth muscle tumors have histologic features that are not worrisome enough to render an unequivocal diagnosis of sarcoma. These tumors can be classified as atypical leiomyomas, smooth muscle tumors with low malignant potential (low probability of an unfavorable outcome), or smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP) (insufficient numbers have been studied to predict their behavior). Figure 9.4 summarizes the classification of uterine smooth muscle tumors based on their histologic characteristics. It is recommended that unusual cases be reviewed by a gynecologic pathologist. Histologic parameters of leiomyosarcomas that have been shown to be prognostic indicators include grade, mitotic rate, extensive tumor cell necrosis, lymphovascular invasion, and ER/PR status.

Figure 9.4 Uterine smooth muscle tumors (excluding epithelioid and myxoid types and cervical tumors). (AWD, alive with disease; DOD, dead of disease; hpf, high-power fields; LMP, low malignant potential; NED, no evidence of disease; SMT, smooth muscle tumor.)

Carcinosarcoma

Uterine carcinosarcomas, also called malignant mixed müllerian tumors, are lesions containing carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements. Numerous studies have shown that these tumors are clonal malignancies derived from a single stem cell and should be considered “metaplastic carcinomas.” Microscopically, these tumors have a typical biphasic pattern with carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements. The carcinoma is usually high grade; the sarcomatous component is always high grade and may be homologous or heterologous. Homologous elements are those components that are native to the uterine body and most commonly are high-grade fibrosarcoma, although other varieties such as undifferentiated sarcoma may be found as well. Heterologous elements are those components that are not normally found within the uterus. Heterologous elements are seen in half of the cases. The most common heterologous sarcoma is rhabdomyosarcoma, followed by chondrosarcoma, and, less often, osteosarcoma and liposarcoma.

Most studies suggest that the behavior of carcinosarcomas is predicted by the carcinomatous component. Tumors typically metastasize through lymphatic channels similar to endometrial carcinomas. Most metastases and recurrences are composed of pure carcinoma. In two recent studies, adverse prognostic factors included the following: heterologous elements (in stage I tumors) and high percentage of sarcomatous component in the main tumor and in the recurrences. Data from The Cancer Genome Atlas indicate that approximately 90% of carcinosarcomas harbor TP53 mutations.

Endometrial Stromal Neoplasms

In the current World Health Organization classification, endometrial stromal tumors are classified into endometrial stromal nodules, ESS (by definition low grade), and undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma. Both endometrial stromal nodules and ESS are composed of cells identical to those found in the stroma of proliferative endometrium. Undifferentiated endometrial sarcomas, on the other hand, are high-grade sarcomas that do not resemble endometrial stroma, and a diagnosis is made by excluding other uterine sarcomas.

The differential diagnosis between an endometrial stromal nodule and an endometrial stromal sarcoma is important since the nodules are always benign lesions. Differential diagnosis is based upon the presence of infiltrating margins with or without angioinvasion in endometrial stromal sarcoma. These two features are not seen in stromal nodules, which are always well circumscribed and have pushing margins. It is impossible to render a definitive diagnosis based upon curettage material alone; final diagnosis requires a hysterectomy specimen.

Most ESS have fewer than 10 mitoses/10 hpf, but even mitotically active variants behave in a similar indolent manner. Sixty percent of low-grade endometrial stromal tumors (including ESS and stromal nodule) have cytogenetic abnormalities involving rearrangements of chromosomes 6, 7, and 17. The most characteristic translocation of these tumors, t(T7;17) (Tp15;q21), generates a fusion of the JAZF1 and JJAZ1 genes, both of which encode zinc finger proteins.

Undifferentiated endometrial sarcomas have cytologic atypia to the extent that they cannot be recognized as arising from endometrial stroma. Morphologically, these high-grade lesions resemble undifferentiated mesenchymal tumors and behave as high-grade sarcomas. It is advisable to use a term such as “high-grade sarcoma,” “undifferentiated sarcoma,” or “poorly differentiated uterine sarcoma” rather than “endometrial stromal sarcoma.” This last term may inaccurately suggest an indolent tumor. Undifferentiated uterine sarcomas are usually seen in patients older than 50 years, have a recurrence rate of over 85%, and are usually fatal.

Müllerian Adenosarcoma

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree