Collapse and Cardiorespiratory Arrest

Not all children who collapse will proceed to a full respiratory or cardiac arrest. Causes of sudden collapse in children are listed in the box and many of these are discussed in detail in Chapters 40 and 57. However, if basic life support is not provided urgently, a collapsed child may progress to cardiorespiratory arrest, often due to failure to maintain an open airway.

Sudden Collapse in Children

- Syncope (vaso-vagal)

- Epilepsy

- Choking

- Cardiac arrhythmia (rare)

- Factitious illness (rare)

- Hypoglycaemia

- Drug ingestion

- Anaphylaxis

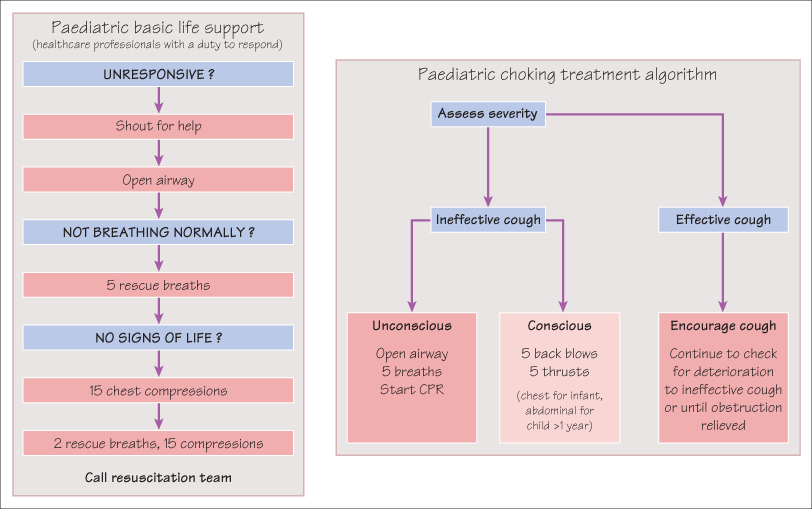

Cardiac arrest is the end-point of severe respiratory or cardiac failure that has either been overwhelming or has not been adequately treated. Cardiorespiratory arrest outside hospital requires rapid basic life support until skilled help arrives. In hospital, arrest should be managed by a skilled resuscitation team. As most cardiorespiratory arrests in children are secondary to hypoxia rather than due to cardiac disease it is crucial to achieve a patent airway and adequate oxygenation using high-flow oxygen and artificial respiration and where necessary (e.g. asystole or severe bradycardia) to circulate this oxygen by use of cardiac massage.

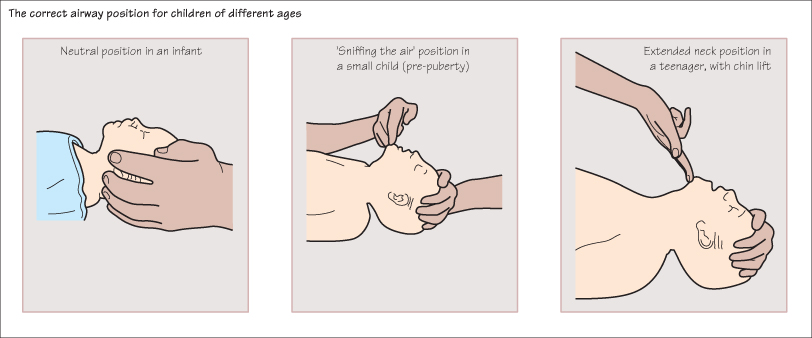

Establishing an Airway and Artificial Ventilation

The airway should be opened by lifting the chin and tilting the head back to a ‘sniffing the air’ position. In infants the head should be in the neutral position. If there is a possibility of cervical spine injury then the airway should be opened by the ‘jaw-thrust’ method, while a helper supports the cervical spine. The airway should then be cleared by removing any vomit or secretions with suction. Artificial ventilation can be given by mouth to mouth or in infants by mouth to mouth and nose. After five rescue breaths check for signs of circulation (i.e. moving, normal breathing, coughing or presence of a central pulse). If there are no signs of life then commence cardiac massage.

Choking

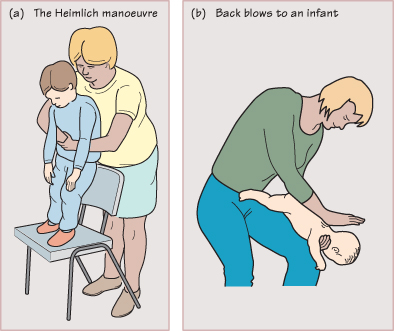

Children are at high risk of obstructing their airway with a foreign body. This is partly due to their nature (toddlers putting small objects in their mouths, older children throwing food in the air or sucking on pen-tops) and partly due to the small size of the airway and the anatomy. A child’s airway is conical, with the narrowest part at the cricoid ring, so objects tend to lodge in a position where they can cause complete airway obstruction. This leads to sudden onset of choking, cyanosis and collapse. Choking should be managed by encouraging coughing or in the unconscious child by opening the airway, removing any visible obstruction and performing alternating back blows and chest/abdominal thrusts to expel the obstruction. Abdominal thrusts (the Heimlich manoeuvre) should not be attempted in infants because of the risk of trauma to the liver and spleen; instead, perform five alternate back blows and chest thrusts with the child held in a head-down position. If these measures are unsuccessful ventilation will be required via an emergency tracheostomy or crico-thyroidotomy.

External Cardiac Massage

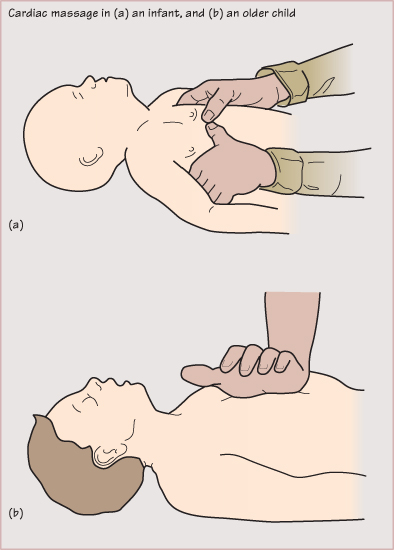

In infants cardiac massage can be achieved by encircling the chest with both hands and compressing the lower third of the sternum with the thumbs. In young children the heel of one hand is used and in older children two hands are used. A ratio of 15 compressions to 2 breaths is used for all ages except newborn infants, where the ratio is 3 : 1.

If these measures are not effective then drugs such as adrenaline (epinephrine), sodium bicarbonate and a fluid bolus may be necessary, depending on the cause of the cardiac arrest. Adrenaline can be given via the intravenous or intraosseous routes. Endotracheal adrenaline should only be used if intravenous or intraosseous access is impossible, as the evidence for efficacy is not good. Defibrillation is very rarely required in paediatric cardiac arrests, but is indicated for certain cardiac arrhythmias such as ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia and supraventricular tachycardia unresponsive to drug therapy. Life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias are more common in children with congenital heart disease (postoperatively), drug ingestion (e.g. overdose of a tricyclic antidepressant) and in those with a long QT interval on the ECG.

Focal Points for the Assessment of the Collapsed Child

- Call for help immediately.

- Make a rapid assessment of the child’s responsiveness—stimulate and say ‘are you all right?’. Do not shake the child.

- If the child responds and is breathing with an open airway, leave them in this position and await help.

- If the child does not respond and is not breathing, proceed with basic life support.

- If the child is breathing normally but not responding to you, turn them onto their side in the recovery position.

- Continue basic life support uninterrupted until help arrives. If help has not arrived after 1 minute of CPR then go and get help.

- Apply pressure to any active bleeding points.

- Rapidly assess the neurological state by looking at pupils, posture and the level of consciousness.

- Once help arrives, or if in a hospital setting:

- Continue basic life support uninterrupted.

- Commence advanced life support (e.g. tracheal intubation, vascular access, administration of drugs) as indicated.

- Commence monitoring (ECG, oxygen saturation).

- Always check blood sugar level.

- Continue basic life support uninterrupted.

- Perform appropriate investigations and commence definitive treatment (e.g. infection screen and broad spectrum antibiotics if sepsis is suspected).

- Once the child has been stabilized, transfer to an intensive care unit for definitive care.

KEY POINTS

- Cardiac arrest is usually secondary to respiratory failure or shock.

- Upper airway obstruction is a common cause of acute respiratory failure in young children.

- Opening the airway and providing adequate oxygenation is critical.

- The technique of basic life support is a practical skill which you should acquire.