Chapter 441 The Anemias

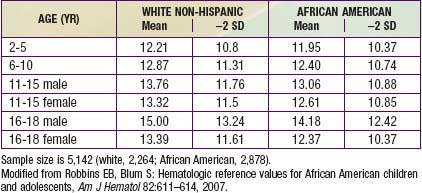

Anemia is defined as a reduction of the hemoglobin concentration or red blood cell (RBC) volume below the range of values occurring in healthy persons. “Normal” hemoglobin and hematocrit (packed red cell volume) vary substantially with age and sex (Table 441-1). There are also racial differences, with significantly lower hemoglobin levels in African-American children than in white non-Hispanic children of comparable age (Table 441-2).

Table 441-1 NORMAL MEAN AND LOWER LIMITS OF NORMAL FOR HEMOGLOBIN, HEMATOCRIT, AND MEAN CORPUSCULAR VOLUME

Table 441-2 NHANES III HEMOGLOBIN VALUES FOR NON-HISPANIC WHITES AND AFRICAN AMERICANS AGED 2-18 YEARS

Differential Diagnosis

Anemia is not a specific entity but rather can result from any of number of underlying pathologic processes. In order to narrow the diagnostic possibilities, anemias may be classified on the basis of their morphology and/or physiology (Fig. 441-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree