Teratomas, Dermoids, and Other Soft Tissue Tumors

Teratomas

Embryology and Pathology

Teratoma, from the Greek teratos (‘of the monster’) and onkoma (‘swelling’), is a term first applied by Virchow in 1869 to ‘sacrococcygeal growths’.1 Teratomas are composed of multiple tissues foreign to the organ or site from which they arise.2 Although teratomas are sometimes defined as having three embryonic layers (endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm), recent classifications also include monodermal types.2,3

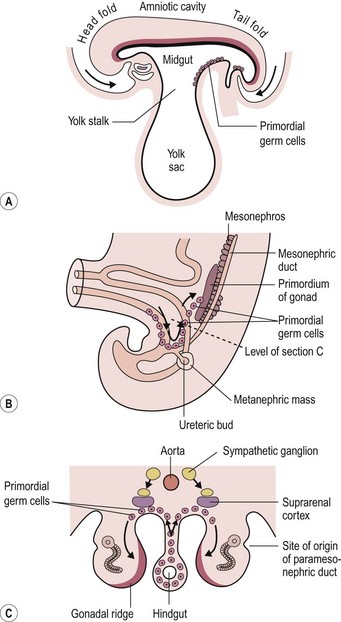

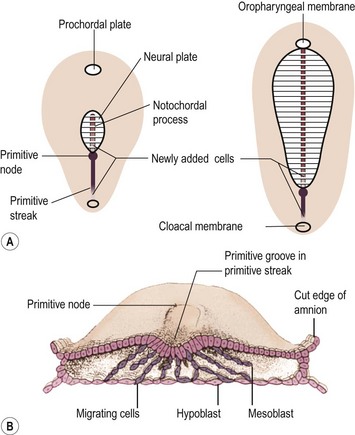

Teratomas are thought by some to arise from totipotent primordial germ cells.3 These cells develop among the endodermal cells of the yolk sac near the origin of the allantois and migrate to the gonadal ridges during weeks 4 and 5 of gestation (Fig. 68-1).4 Some cells may miss their target destination and give rise to a teratoma anywhere from the brain to the coccygeal area, usually in the midline. Another theory has teratomas arising from remnants of the primitive streak or primitive node.4–6 During week 3 of development, midline cells at the caudal end of the embryo divide rapidly and, in a process called gastrulation, give rise to all three cell layers of the embryo (Fig. 68-2).4 By the end of week 3, the primitive streak shortens and disappears. This theory explains the more common occurrence of teratomas in the sacrococcygeal region. With either theory, the totipotent cells could give rise to monoclonal neoplasms. Evidence shows that, whereas immature teratomas may be monoclonal, mature teratomas can be polyclonal, more like a hamartoma than a neoplasm.7 This finding is compatible with the third theory that teratomas are a form of incomplete twinning.2,3

FIGURE 68-1 Commonly cited theory on the origin of teratomas. (A) Drawing of embryo during week 4 (longitudinal section), showing primordial germ cells at the base of the yolk sac. (B, C) During week 5, these cells migrate toward the gonadal ridges. According to this theory, some cells could miss their intended destination. (Modified from Moore KL, Persaud TVN. The Developing Human. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1993. p. 71, 181.)

FIGURE 68-2 Alternate theory on embryogenesis of teratomas. (A) Sketches of dorsal views of the embryonic disk on days 17 and 18, showing the primitive streak and primitive node. (B) Drawing of a transverse cut of the embryonic disk during week 3. This shows that cells from the primitive streak migrate to form the mesoblast (the origin of all mesenchymal tissues) and also displace the hypoblast to form the endoderm. Hence, remnants of these pluripotent primitive streak cells could give rise to teratomas and could account for the more frequent sacrococcygeal location. (From Moore KL, Persaud TVN. The Developing Human. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1993. p. 55–6.)

The primordial germ cell is the principal but probably not the exclusive progenitor of a teratoma. The recent trend is to include teratomas under the classification of germ cell tumors.2,3,5 This histologic classification also includes germinomas (formerly dysgerminomas), embryonal carcinomas, yolk sac tumors (YST), choriocarcinomas, gonadoblastomas, and mixed germ cell tumors. Gonadal and extragonadal teratomas may have a different origin, explaining the different behavior according to tumor site.

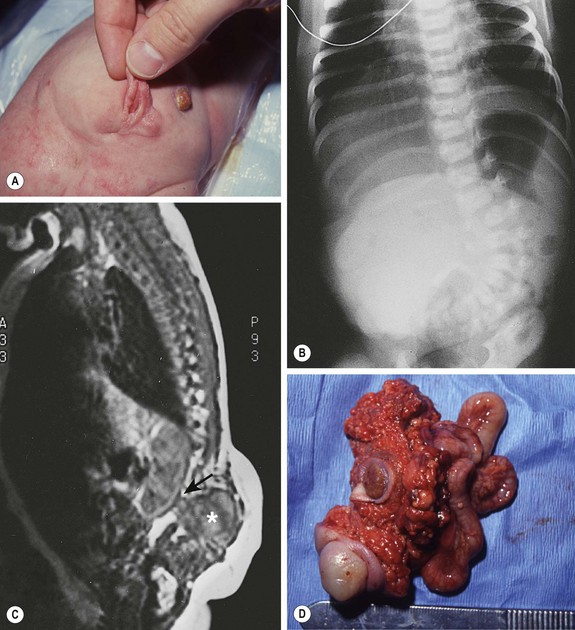

Teratomas are fascinating tumors owing to the diversity of tissues they may contain and the varying degree of organization of these tissues. Many tumors contain skin elements, neural tissue, teeth, fat, cartilage, and intestinal mucosa, often with normal ganglion cells. These tissues are usually present as disorganized islands of cells with cystic spaces. The tumor sometimes consists of more organized tissue, such as small bowel, limbs, and even a beating heart. These have been called fetiform teratomas (Fig. 68-3).2,3,5,8,9 When the mass includes vertebrae or notochord and a high degree of structural organization, the term fetus in fetu is used. This is viewed by some as a variant of conjoined twinning but is classified as a teratoma by others, owing to the absence of a recognizable umbilical cord in its vascular pedicle.3,10 Whether teratomas are at one end of a spectrum that includes fetus in fetu, parasitic twins, conjoined twins, and normal twins is the subject of controversy. One certainly cannot dismiss the many reports of teratomas associated with fetus in fetu in the same patient and with a twin pregnancy.2,3,11–13

FIGURE 68-3 (A) This child had a large fluctuant lumbar mass at birth. The patient is prone with the head at the top of the photograph. A family history of myelomeningocele existed in a great aunt. She also had an atrophic right leg with neurologic impairment below the L3 root and clubbing of the right foot. Note the ulcerated, arachnoid-looking area cranially and the pedunculated skin caudally, which had the appearance of a vulva and was oozing serous fluid. (B) Plain radiograph shows a severe lumbosacral scoliosis with vertebral anomalies. CT confirmed the vertebral anomalies with spina bifida and demonstrated a pattern of intestine with inspissated or calcified meconium in the teratoma. (C) MR image reveals that the mass (asterisk) extended into the retroperitoneum, where it was contiguous with the lower pole of the right kidney (arrow). (D) At operation, normal-looking blind bowel loops were found deep to the vulva-like structure. Part of the mass extended along the spinal cord, which required dissection and untethering by a neurosurgeon. The pathologic diagnosis was a mature fetiform teratoma that contained, among many other things, two adrenals, two ovaries, renal tissue with some glomeruli and tubules, bone with bone marrow, and portions of stomach and small and large bowel. The child recovered well neurologically but required spinal instrumentation owing to progressive scoliosis at age 2 years.

The overall tissue architecture is variable in teratomas. Moreover, a spectrum of cellular differentiation exists. Most benign teratomas are composed of mature cells, but 20–25% also contain immature elements, most often neuroepithelium. However, the degree of histologic immaturity is of proven prognostic significance only in ovarian teratomas.3,14 Even this concept is being questioned, since one large cooperative study demonstrated that overlooked microscopic foci of YST, rather than the grade of immaturity, was more predictive of recurrence.15 In neonatal teratoma, immature tissue is considered normal and without any influence on prognosis.2,5,16 Spontaneous maturation of malignant tumors has been reported after partial excision of giant SCTs in two fetuses at 23 and 27 weeks of gestation.17

Teratomas may also contain or develop foci of malignancy. A malignant germ cell tumor may be found in sites typical for teratomas, such as the mediastinum or sacrococcygeal area. Whether the lesion was malignant from the onset or the malignant cells destroyed and replaced the benign teratoma component is often difficult to ascertain. The most common malignant component within a teratoma is a YST (formerly also called ‘endodermal sinus tumor’). Other malignant germ cell tumors can occur, and, rarely, malignancy in other tissues composing the teratoma, such as neuroblastoma,18,19 squamous cell carcinoma,20 carcinoid,21 and others, can develop. Malignancy at birth is uncommon but increases with age and with incomplete resection. An apparently mature teratoma may recur several months or years after resection as a malignant YST, illustrating the difficulties in histologic sampling of large tumors and the need for close follow-up.2,3

Most YSTs and some embryonal carcinomas secrete α-fetoprotein (AFP), which can be measured in the serum and demonstrated in the cells by immunohistochemistry.22 This marker is particularly useful for assessing the presence of residual or recurrent disease. AFP levels are normally very high in neonates and decrease with time.22,23 The postoperative half-life is about six days. Persistently high levels may be an indication for the need for further surgical procedures or chemotherapy. Other markers that may be elevated are β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG), produced by choriocarcinomas, and, rarely, carcinoembryonic antigen. CA 125 was also found helpful in the follow-up of patients with SCTs, but not CA 19–9.24 Secretion of β-hCG by the tumor may be sufficient to cause precocious puberty.25

The genetic basis of teratomas is not yet understood. Most germ cell tumors appear to have an amplification, or isochromosome, in a region of the short arm of chromosome 12, designated i(12p).3,26 This has been well described in adults but was not confirmed in one pediatric series in which deletions on chromosomes 1 and 6 were found instead.27 Similarly, oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes did not appear to correlate with prognosis in one study.28 MYCN gene amplification was present in immature teratomas, but absent in mature teratomas in another report.29 BAX mutation and overexpression correlated with survival in another study of childhood germ cell tumors.30 The clinical usefulness of these findings remains unclear.

Associated Anomalies

Teratomas are usually isolated lesions. A well-recognized association is the Currarino triad of anorectal malformation, sacral anomaly, and a presacral mass.31,32 The presacral mass is usually a teratoma or an anterior meningocele. However, hamartomas, duplication cysts, and dermoid cysts have been described, as have combinations of these lesions.

An extensive review of the English and German literature found 51 cases of infants with the Currarino triad and highlighted several important facts.33 Twenty per cent of patients were older than 12 years at the time of diagnosis, yet no reports of malignancy were found. This contrasts to a 75% malignancy rate in patients older than 1 year who had the usual SCT.34 However, a subsequent case report described a malignant recurrence that resulted in the patient’s demise at 4 years of age despite chemotherapy.35 Since then, more reports of malignant transformation of a presacral teratoma in the context of the Currarino triad have appeared, and the risk of malignant transformation has been estimated at 1%.36,37 This can occur well into adulthood.38 Hence, one should not dismiss the presacral mass as always being benign in these patients. The female preponderance for patients with this triad is 1.5 : 1, which is less than the 3 : 1 ratio noted in isolated SCTs. A familial predisposition is noted in 57% of cases and has an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern.39 Although all variants of anorectal malformations have been described, by far the most common is anal or anorectal stenosis. In one report, this triad was present in 38% of all patients with anorectal stenosis and in 1.6% of patients with low imperforate anus.40

Anal anomalies also have been reported in conjunction with a presacral mass, but in the absence of sacral defects. Hirschsprung disease has been incorrectly diagnosed in some cases,41,42 indicating the need to eliminate the presence of a presacral mass by digital rectal examination, by a metal sound when the anus is too tight, or by imaging studies. In the screening of family members, normal plain radiographs of the sacrum are not adequate, because a presacral mass may exist in the absence of a bony defect.43 The low incidence of malignancy has led one author to conclude that the presacral lesion in this context is a hamartoma rather than a teratoma.44 This is supported by the demonstration of deletions or mutations of the homeobox gene HLXB9, located at 7q36, in several affected families.45 In two families where one member had died from a malignant neuroendocrine tumor originating from a presacral teratoma, the diagnosis of Currarino syndrome was made through identification of a HLXB9 mutation.36,38

The mutated gene has recently been renamed ‘motor neuron and pancreas homeobox 1 (MNX1).’45a Urogenital anomalies, such as hypospadias, vesicoureteral reflux, vaginal or uterine duplications, and other anomalies are associated with teratomas.32,34,46,47 Congenital dislocation of the hip has been found in 7% of patients with SCTs which can lead to late orthopedic sequelae.48 Vertebral anomalies can also be found (see Fig 68-3). Central nervous system lesions, such as anencephaly, trigonocephaly, Dandy–Walker malformations, spina bifida, and myelomeningocele can occur as well.2,3,49,50 Another peculiar association with SCTs is a family history of twins in as many as 10% of the patients.39,51,52 Although not confirmed in all series, this finding, combined with reports of simultaneous twin pregnancy or sequential familial occurrences of fetus in fetu and teratoma, supports the theory that teratomas may be just one end of the spectrum of conjoint twinning.2,3,9

Klinefelter syndrome is strongly associated with mediastinal teratoma50,53 and has been reported in patients with intracranial54 and retroperitoneal tumors.55 It is estimated that 8% of male patients with primary mediastinal germ cell tumors have Klinefelter syndrome, which is 50 times the expected frequency.53 These tumors are often malignant, are of the choriocarcinoma type, secrete β-hCG, and produce precocious puberty. Histiocytosis and leukemia are also associated with mediastinal teratoma, both with and without Klinefelter syndrome.56–58 Other hematologic malignancies, such Hodgkin disease, occur rarely.59

The following rare associations have been reported, most often with nonsacrococcygeal lesions: trisomy 13, trisomy 21, Morgagni hernia, congenital heart defects, Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome, pterygium, cleft lip and palate, and rare syndromes, such as Proteus and Schinzel-Giedion syndromes.49,50,60–64

Diagnosis and Management by Tumor Site

Sacrococcygeal Teratoma

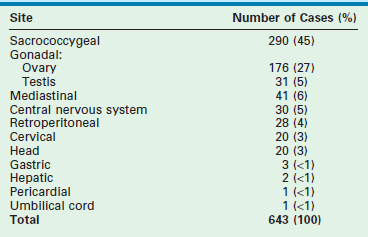

SCTs account for 35–60% of teratomas (gonadal included) in large series (Table 68-1).65–67 This is the most common tumor in the newborn, even when stillbirths are considered.49 The estimated incidence is 1 per 35,000 to 40,000 live births.3,16

TABLE 68-1

Relative Frequency of Teratomas by Site

Data are from five series of teratomas in children.

Modified from Dehner LP. Gonadal and extragonadal germ cell neoplasms: Teratomas in childhood. In: Finegold M, editor. Pathology of Neoplasia in Children and Adolescents. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1986. p. 282–312.

Diagnosis.

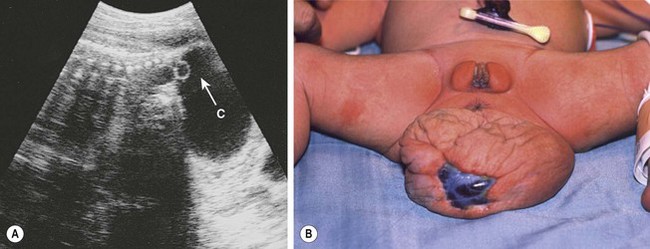

In countries where prenatal ultrasonography (US) is not readily available, most SCTs are seen as a visible mass at birth, making the diagnosis obvious (Fig. 68-4). Prenatal diagnosis has important implications and will be discussed further.

FIGURE 68-4 This infant was diagnosed with a large sacrococcygeal teratoma in utero. Within days, premature labor occurred, prompting cesarian delivery at 25 weeks gestation. The baby died despite resuscitation attempts.

There is an unexplained female preponderance of 3 : 1.34,65,67 The main differential diagnosis is meningocele. Typically, meningoceles occur cephalad to the sacrum and are covered by dura, but sometimes they are covered by skin. Examination of the child reveals bulging of the fontanelle with gentle pressure on a sacral meningocele, helping to establish the diagnosis before plain radiography, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirms it. The co-existence of meningocele with teratoma is well recognized in the familial form, but these are usually presacral. Rarely, a typical exophytic teratoma may have an intradural extension.68,69 Other lesions in the differential diagnosis of neonatal sacrococcygeal masses include lymphangiomas, lipomas, tail-like remnants (Fig. 68-5), meconium pseudocysts, rectal duplications, and several other rare conditions.34,70–73

FIGURE 68-5 This patient had a scrotum-like perianal mass with anal stenosis at birth. An anoplasty was done with removal of the mass, which was not attached to the coccyx. Pathology showed only fibroadipose tissue with smooth muscle, vascular structures, and cartilage, consistent with a hamartomatous process or caudal vestige (also called a tail remnant).

Although many neonates with SCTs do not have symptoms, some require intensive care because of prematurity, high-output cardiac failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and tumor rupture or bleeding within the tumor.74–78 Lethal hyperkalemia from tumor necrosis has also been described.79 Lesions with a large intrapelvic component may cause urinary obstruction.78,80 Besides looking for signs of a myelomeningocele, the physical examination should always include a rectal examination to evaluate for an intrapelvic component. The most helpful imaging studies consist of plain anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the pelvis and spine, looking for calcifications in the tumor and for spinal defects, and ultrasound of the abdomen, pelvis, and spine. Further preoperative studies are unnecessary in most newborns.

The diagnosis of purely intrapelvic teratomas is often delayed.34 Children develop constipation, urinary retention, an abdominal mass, or symptoms of malignancy, such as failure to thrive. Age is a predictor of malignancy in patients with testicular, mediastinal, and SCTs.2 The risk of malignancy is less than 10% at birth, but rises to more than 75% after age 1 year for SCTs, with the exception of familial presacral teratomas. The risk of malignancy also is high for incompletely excised lesions. Complete excision of the tumor should be carried out as soon as the neonate is stable enough to undergo the operation. Serum markers should be determined before the operation for later comparison.

In recent decades, the diagnosis has often been made on prenatal ultrasound, especially when this examination is routinely performed in the second trimester. The site of the lesion, its complex appearance, and intrapelvic extension, with or without urinary tract obstruction, are easily recognized. Although most small teratomas do not adversely affect the fetus, the presence of a large solid vascular tumor is associated with a significant mortality rate, both in utero and perinatally.75,76,78,81–83 Perinatal mortality is usually related to prematurity or tumor rupture with exsanguination (or both). Premature delivery may occur spontaneously from polyhydramnios or may be induced urgently because of fetal distress or maternal pre-eclampsia.

Repeated ultrasound assessment of tumor size is important because the fetus should be delivered by cesarean section if the tumor is larger than 5 cm or larger than the fetal biparietal diameter.84 Dystocia during vaginal delivery is associated with tumor rupture and hemorrhage, and is an avoidable obstetric complication. The options in managing unexpected cases with dystocia include emergency cesarean completion of the partially delivered fetus, who has been intubated and ventilated after vaginal presentation of the head.84

Polyhydramnios with larger tumors may lead to premature labor; amnioreduction is often required to decrease uterine irritability.78,83 Tumors that are larger than the fetal biparietal diameter at diagnosis, or that grow faster than the fetus or grow faster than 150 mL/week, are associated with a poor prognosis.82,85 As the tumor enlarges, the fetus may develop placentomegaly or hydrops, caused by high-output cardiac failure from vascular shunting within the tumor, with fetal anemia from intratumoral bleeding also playing a role. This is a harbinger of impending fetal death and should lead to urgent cesarean delivery, especially when the maternal mirror syndrome has developed.86 Open fetal surgical excision/debulking is one option in fetuses considered too premature to deliver. It has been performed with success in three of eight cases in one center and in three of four cases in another.76,87 Interestingly, there were no cases of fetal resection in the latter center in a more recent cohort of 23 fetuses with SCT, emphasizing that the indications for such a procedure are limited.82

As a result of the maternal and fetal risks, less invasive therapeutic options have been sought. Successful intrauterine endoscopic laser ablation of the large feeding arteries has been described.88 There have been several other reports, a few with good outcomes, but some with poor outcomes often related to severe fetal anemia and cardiac failure.78,89,90 Alcohol injection has also been used.78 Attempts at interrupting the high vascular flow have also been described by using radiofrequency ablation, with two survivors in the first four attempts.91 One survivor had significant perineal damage.92 As the technology has improved, there seems to be a renewed interest in this approach.93–95 However, it remains unclear when early delivery is preferable to intervention in utero in fetuses with early hydrops and placentomegaly. Some advocate a fetal operation before 30 weeks of gestation,82 with the same group recently suggesting early delivery in selected fetuses after 27 weeks of gestation.96 Others have reported survival after emergency delivery as early as 26 weeks of gestation.97 The EXIT procedure (ex utero intrapartum treatment) has been used as an adjunct to allow safer resection of a ruptured teratoma in a 27 week gestation fetus, but long-term neurological sequelae were noted.96

Purely cystic teratomas occur in 10–15% of cases. Prenatal diagnosis allows percutaneous aspiration to facilitate delivery (Fig. 68-6), to decrease uterine irritability, or to prevent tumor rupture at delivery.76,78,81,98,99 In another report, prenatal decompression using a cyst-amniotic shunt was successfully performed to relieve the obstructive uropathy caused by the cystic teratoma.100 Fetal MRI is a useful adjunct to the prenatal evaluation, providing additional information that aids in counseling and preoperative planning.101 It also helps in the differential diagnosis when the teratoma is entirely presacral.102

FIGURE 68-6 (A) Ultrasound image of a female fetus at 38 weeks of gestation, showing a large cystic mass (C) attached to the coccyx, with tiny cysts anterior to the sacrum (arrow). An ultrasound evaluation at 18 weeks was normal. The cyst was gradually enlarging from an initial diameter of 9.5 cm at 31 weeks of gestation. The cyst was aspirated for 650 mL of fluid, permitting external rotation from breech to the vertex position. Two days later, when labor was induced, another 200 mL of fluid was removed to permit an uncomplicated vaginal delivery. (B) Twenty-four hours postnatally, the lesion remained floppy with an area of skin ulceration, likely a consequence of excessive in utero distention. A mature cystic teratoma was confirmed histologically.

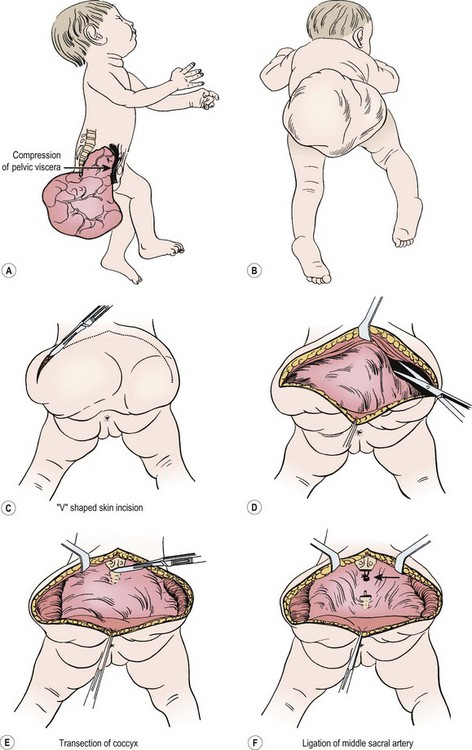

Operative Approach.

For most tumors, the major component is extrapelvic and the patient is placed in the prone position. If a significant intrapelvic or intra-abdominal component is present, or if the tumor is highly vascular and bleeding within the tumor is suspected, it may be wise to begin with a laparotomy or laparoscopy (see above). Generally, most resections can be achieved completely in the prone position, especially if the internal portion is cystic (Fig. 68-7).78 When in doubt, a safe approach is to prepare the skin from the lower chest to the toes, allowing the infant to be turned to the supine position without having to re-drape. Vaseline packing in the rectum facilitates its identification throughout the procedure. En bloc excision, including the coccyx, is preferable. Failure to remove the coccyx is associated with a high recurrence rate.2,3,103 An acceptable gluteal crease and perineum is formed by the appropriate positioning of the perianal musculature. The use of plastic surgical principles to close the skin improves the cosmetic appearance of the scar (see Fig. 68-7, inset).104

FIGURE 68-7 (A) The teratomatous attachment may compress the rectum, vagina, and bladder anteriorly. (B) The patient is placed on the operating table in a prone jackknife position, with general endotracheal anesthesia. An appropriate intravenous cannula should be placed in an arm vein. (C) The incision is an inverted V-shape to allow excision of the tumor and to facilitate an eventually satisfactory cosmetic closure. The amount of skin excised is dependent on the size and shape of the tumor. (D) The tumor is dissected from the gluteus maximus muscle. (E) The coccyx is transected and removed in continuity with the tumor. (F) The middle sacral artery is the major blood supply to the tumor and is ligated (arrow) after transection of the coccyx. (G) Excess skin is excised to facilitate closure. (H) As the tumor is adherent to the rectum, sharp dissection can be directed by placing a finger in the rectum. (I) Placement of sutures between the anal sphincter and the presacral fascia (a). When the sutures are tied, the anal sphincter is pulled upward to the sacrum to form a gluteal crease (b). (J) A drain is left in the surgical site for drainage of postoperative serosanguineous fluid. Inset, Recently described technique for closure after excision of large teratomas. Using plastic surgery principles, this avoids ‘dog ears’ and places the scars along natural skin lines for a much-improved long-term cosmetic result. (K) If the tumor extends through the bony pelvis into the retroperitoneum, a urinary bladder catheter is inserted to facilitate suprapubic dissection. (L) Lower abdominal transverse incision allows interruption of the middle sacral artery and dissection of the tumor from the sacrum and pelvis, which is eventually removed from the perineum. (Inset redrawn from Fishman SJ, Jennings RW, Johnson SM, et al. Contouring buttock reconstruction after sacrococcygeal teratoma resection. J Pediatr Surg 2004;39:439–41; with permission.)

Although the chevron incision has been used by most surgeons, a vertical incision is sometimes advantageous. It is preferred for smaller teratomas because it leaves a nearly normal-looking median raphe (Fig. 68-8). Resection of the excess skin at the closure gives an optimal cosmetic result. Others have reported using this approach for large tumors as well.105

FIGURE 68-8 Smaller cystic teratoma at age 1 month, initially mistaken for a hemangioma owing to its soft compressible nature and bluish skin discoloration. This tumor lends itself well to a longitudinal elliptical excision with midline closure, as in a posterior sagittal anorectoplasty.

Several techniques have been described to help in the management of giant SCTs. These include intraoperative snaring of the aorta,77 laparoscopic division of the median sacral artery,106,107 the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and hypothermic perfusion,108 devascularization and staged resection,97,109 and preoperative embolization with or without radiofrequency ablation.110,111 Autologous cord blood transfusion is another useful adjunct.112

Prognosis.

Fetuses with an SCT diagnosed in utero have a survival rate in excess of 90% if the tumor is small and discovered by routine prenatal ultrasound. If a complicated pregnancy is the indication for ultrasound evaluation, the mortality increases to 60%. Nearly 100% of patients die when hydrops or placentomegaly develop.76,78,81,113 Dystocia or tumor rupture during delivery are likely underreported as a cause of mortality.83,114 In one series, 10% of babies died during transfer, all before the widespread use of antenatal ultrasound.115 In a report describing 24 patients with a SCT diagnosed on routine obstetric ultrasound, 3 were aborted electively, four died in utero at 20 to 27 weeks of gestation, and three died of tumor rupture during delivery at 29 to 35 weeks of gestation (one after vaginal and two after cesarean delivery).75 The incidence of placentomegaly (none), hydrops (5%), and polyhydramnios (19%) was lower than in series in which ultrasound was performed for an obstetric reason.76,84,116 Tumor size, vascularity, and content were used to develop a prognostic classification from a cohort of 44 fetal SCTs.117 Fifty per cent of infants with tumors 10 cm or greater that were highly vascular or fast growing died, whereas none died if these features were absent or if the tumor was predominantly cystic. Recently, a growth rate >150 mL/week was found to be associated with an increased risk of perinatal mortality.82 A vena cava diameter ≥6 mm and cardiac output ≥600 mL/kg/min have also been used to detect high-output cardiac failure in the early stages.82 Another prognostic classification involves the ratio of solid tumor volume over the head volume.118 In a series of 28 cases, none of the fetuses with STV/HV ratio <1 died, while 61% with a ratio >1 died. The same center has also reported risk stratification based on fetal echocardiographic findings.119 Finally, the ratio of tumor volume over fetal weight was found to be an early prognostic marker.120

In the absence of severe prematurity and perinatal complications, the prognosis is dependent on the presence of malignancy and is therefore related to age at operation and completeness of resection.121,122 When the tumor is benign and completely excised, recurrence is low, unless the tumor is large and mostly solid.123 The recurrent tumor may be benign or malignant, and benign metastatic tissue may become evident in lymph nodes.124 Although immature or fetal elements in gonadal teratomas are associated with a higher risk of aggressive behavior, this is not considered true for SCTs.2,5,16 However, a multicenter study identified immature histology, in addition to malignancy and incomplete resection, as risk factors for recurrence.122 Although malignant recurrence of a ‘benign’ teratoma may be as high as 10–15%,6,122 the original benign diagnosis may have been due to sampling error,15 an undetected residual microscopic focus of malignant tumor,125 or secondary to incomplete coccygectomy at the initial operation.35 Patients whose tumors are resected after the newborn period have a higher risk of malignant recurrence, especially when an elevated AFP level is present at diagnosis. The elevated AFP likely signifies the presence of malignancy in the original tumor.15,126 It is important to monitor all patients by physical examination, including rectal examination and serum markers (AFP and CA 125), every two or three months for at least 3 years because most recurrences occur within three years of operation.24,127

Recurrent disease is usually local, but metastases to inguinal nodes, lung, liver, brain, and peritoneum can occur, including pseudomyxoma peritonei.128 The prognosis of a malignant tumor or a malignant recurrence was dismal until the advent of platinum-based chemotherapy.125 Survival rates of 80–90% are now achieved, even in the presence of metastatic disease, but the risk of late recurrences or second malignancies persists.129–131 Older patients presenting with large malignant tumors usually undergo biopsy followed by chemotherapy before resection is attempted to avoid sacrificing vital structures.16,130,132

A Children’s Cancer Group (CCG) review illustrates the shift in mortality causes, from late diagnosis/malignancy to perinatal events.129 The mortality was 10% in 126 patients treated in 15 institutions from 1972 to 1994. Three patients died of severe associated anomalies. Two died of hemorrhagic shock postoperatively and six due to combinations of severe prematurity, birth asphyxia due to failed vaginal delivery, or preoperative tumor rupture. Death from a metastatic YST occurred in one patient. A second patient with metastatic disease was lost to follow-up and is presumed dead. Thus, only two deaths occurred from malignancy, despite a total of 20 YSTs (13 malignant at initial operation, seven malignant recurrences after resection of ‘benign’ teratomas). Owing to the effectiveness of current chemotherapy in treating recurrent disease, as well as its toxicity in young infants, it appears that a completely excised malignant YST does not require adjuvant therapy. These patients should be closely monitored clinically and with serial AFP measurements.133 Similar encouraging results have been found in the German Cooperative Studies.134

In the current era of the rather routine use of ultrasound in pregnancy, the prognosis for patients with an SCT is not dependent on Altman’s classification34 but rather on tumor size, physiologic consequences, histology, and associated anomalies. The prognosis of malignant tumors depends on tumor type, stage, location, and patient age.129 Functional results in survivors have been reported as excellent in most series.78,135,136 However, several reports draw attention to fecal and urinary continence problems, as well as lower limb weakness.121,137–141 Some of these problems are clearly related to associated anomalies,115 the need for reoperation,142 or to the presence of large presacral or intra-abdominal tumors,80,135 but they can occur after excision of purely extrapelvic benign tumors. A good outcome requires meticulous dissection along the tumor capsule, preservation and reconstruction of muscular structures, and long-term follow-up. One group advocates earlier cesarean delivery to minimize urologic sequelae in patients with large tumors causing urinary tract dilatation.139 Others have placed vesico-amniotic shunts in such cases with good outcomes.78,100 Urodynamic studies and surveillance ultrasound are now being performed more regularly in some centers.143 Patients with Currarino syndrome, who often have a tethered cord in addition to the presacral tumor, appear to have an increased risk of bladder and bowel dysfunction.144,145 A poor cosmetic result was noted in more than half of the patients in another review.146 These authors advocate early assessment of bladder, anorectal, and sexual function along with cosmetic results within a structured oncology follow-up program. The technique described by the Boston Children’s group is a major step to improve cosmesis (see Fig. 68-7),104 while others favor a sagittal incision.105

Thoracic Teratomas

The anterior mediastinum is the most common site of thoracic teratomas, which account for 7–10% of all teratomas (see Table 68-1).2,3

Mediastinal Teratomas.

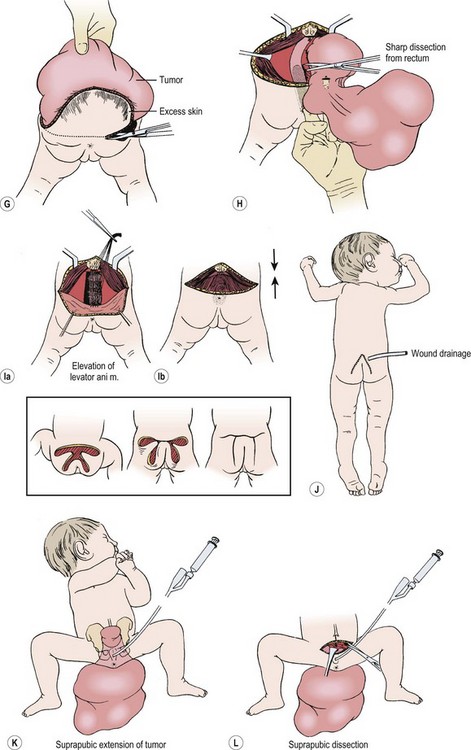

Mediastinal teratomas are diagnosed from the fetal period to adolescence and even adulthood.2,147–149 Most are located in the anterior mediastinum, but a few have been described in the posterior mediastinum, some with epidural extension.150–152 In infants, respiratory distress is a common presenting manifestation,153 but in older children the teratoma is often an incidental finding on chest radiograph (Fig. 68-9).2 Any patient with a mediastinal mass that presents with orthopnea or a reduction in the tracheal cross-sectional diameter of greater than 50% on axial imaging is at a significant risk for airway collapse during general anesthesia.154 In these cases, procedures using local or regional anesthesia may be required to obtain a confirmatory diagnosis. Mediastinal teratomas may be first seen as a chest wall tumor and may even erode through the skin. They also can erode into a bronchus, with hemoptysis as the initial manifestation,155 or rupture into the pleural cavity.156 Secondary pericardial effusion and tamponade have also been described.157 A strong association has been found with Klinefelter syndrome. In these cases, choriocarcinoma in the teratoma often leads to precocious puberty (see under Associated Anomalies).2,25,58 Mediastinal germ cell tumors have also been observed concurrently or after treatment for hematologic malignancies such as Langerhan’s cell histiocytosis and hemophagocytic syndrome.57,158,159 Histologically, the presence of immature tissue does not affect the prognosis in children younger than 15 years. After age 15, mediastinal teratomas have a high incidence of malignant behavior, which is usually indicated by elevated levels of AFP or β-hCG, or both.149 For those with malignancy, YST is most prevalent in girls and young boys while mixed histology prevails in over 50% of older adolescent males.160

FIGURE 68-9 (A) A 13-year-old African boy has an asymptomatic anterior mediastinal mass that was discovered on routine immigration chest radiograph. (B) The CT scan shows a heterogeneous mass adjacent to the aorta, suggestive of a neoplasm (thymoma or lymphoma). During consideration of a fine-needle aspiration biopsy, ultrasonography was done and suggested the presence of cysts with debris (not shown). MRI (not shown) confirmed the presence of the cystic components as well as fat. A mature teratoma was excised through a small left anterior mediastinotomy, removing the left second costal cartilage.

Tumors should be excised through either a median sternotomy or a thoracotomy.16,161 Smaller tumors may be approached through an anterior mediastinotomy (see Fig. 68-9) or by thoracoscopy,162 although tumor seeding is a concern with the latter. Complete resection is the goal, but often these masses are too large at presentation and require initial biopsy followed by chemotherapy.16,163,164 During chemotherapy, attention should be paid to the ‘growing teratoma syndrome’ that occurs when the benign elements within a germ cell tumor continue to grow.165 A Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) and Children Cancer Group (CCG) intergroup study involving 38 patients demonstrated that primary resection could be achieved in 14 patients.160 In another 18, chemotherapy reduced tumor size in 57% while the remainder were stable or increased in size. All patients with residual disease underwent successful post-chemotherapy resection. The overall survival for malignant mediastinal germ cell tumors was 71% which is less than for other extragonadal sites. The prognosis is best for young children with YSTs and worst in older adolescents with mixed germ cell histology.149,160 In a recent series from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, normalization or reduction in preoperative tumor markers was the strongest predictor of increased survival.161

Intrapericardial Teratomas.

Intrapericardial teratomas are most commonly seen in the newborn period or in utero, with evidence of cardiorespiratory distress secondary to pericardial effusions or nonimmune fetal hydrops resulting from cardiac compression.2,3,166 While a fetal diagnosis allows for early postnatal treatment in most newborns, it may also offer an opportunity for antenatal interventions such as fetal pericardiocentesis.167 Early delivery for emergency surgical excision should be considered if the baby develops signs of cardiac tamponade.168 Intrapericardial teratomas are also the leading cause of massive pericardial effusion in the neonate and any delays in diagnosis could be fatal.3,169 In older infants, it may present with respiratory distress or poor feeding. Ultrasound imaging usually demonstrates a cystic or solid teratoma located anterior to the right atrium and ventricle with attachments to the great vessels (see Fig. 25-4).170 The tumor may also be found incidentally on chest radiographs performed for other reasons. The only treatment option for this lesion is excision. On histologic examination, these teratomas are usually composed of mature tissue with or without neuroglial elements.2,3

Intracardiac Teratomas.

Intracardiac teratomas are rare and arise from the atrium or ventricle. Many can be cured by resection.171

Abdominal Teratomas

Retroperitoneal Teratomas.

Retroperitoneal teratomas occur outside the pelvis, often in a suprarenal location. They represent about 4% of all childhood teratomas, and 75% occur in children younger than 5 years.3,173 They occur twice as frequently in females and may have an association with Klinefelter syndrome.16,55

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree