Chapter 22

Systemic Analgesia

Parenteral and Inhalational Agents

Niveen El-Wahab MBBCh, MRCP, FRCA, Roshan Fernando MD, FRCA

Chapter Outline

Systemic drugs have been used to decrease the pain of childbirth since 1847, when James Young Simpson used diethyl ether to anesthetize a parturient with a deformed pelvis. Since that time, the provision of labor analgesia has advanced significantly owing to a heightened awareness of the neonatal effects of heavy sedation or general anesthesia administered during vaginal delivery and a greater desire of women to actively participate in childbirth.

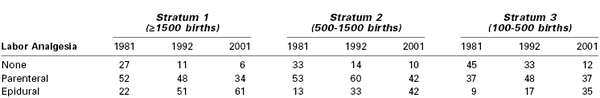

Neuraxial (i.e., epidural, spinal, combined spinal-epidural [CSE]) analgesic techniques have replaced systemic drug administration as the preferred method for intrapartum analgesia in both the United States and Canada (Table 22-1).1,2 By contrast, in the United Kingdom, fewer than one third of parturients received a neuraxial analgesic technique during labor and vaginal delivery in 2011.3

Despite the increased use of neuraxial analgesia for labor, the use of systemic analgesia remains a common practice in many institutions worldwide for several reasons. Many women labor and deliver in an environment where the provision of safe neuraxial analgesia is not available. Some parturients decline neuraxial analgesia or choose to receive systemic analgesia during early labor. Finally, some women may have a medical condition that contraindicates a neuraxial procedure (e.g., coagulopathy) or presents technical challenges (e.g., severe scoliosis, the presence of spinal hardware).

Parenteral Opioid Analgesia

Opioids are the most widely used systemic medications for labor analgesia. These compounds are agonists at opioid receptors (Table 22-2). Their popularity lies in their low cost, ease of use, and the lack of need for specialized equipment and personnel. Although these drugs provide moderate pain relief, parturients commonly report dissociation from the reality of pain rather than complete analgesia. Since neuraxial labor analgesia has become more accessible, systemic opioids have become less popular, owing to the frequency of maternal side effects (e.g., nausea, vomiting, delayed gastric emptying, dysphoria, drowsiness, hypoventilation) and the potential for adverse neonatal effects. However, a renewed interest in opioid administration during labor has occurred owing to the growing use of patient-controlled delivery systems.

TABLE 22-2

Classification of Opioid Receptors

| Current Classification | Previous Classification | Effects |

| µ or MOP | OP3 | Analgesia, meiosis, euphoria, respiratory depression, bradycardia |

| κ or KOP | OP2 | Analgesia, sedation, meiosis |

| δ or DOP | OP1 | Analgesia, respiratory depression |

| Nociception or NOP | OP4 | Inhibition of opioid analgesia* May cause hyperalgesia* |

* Modified from the International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (IUPHAR) database. Available at http://www.iuphar-db.org. Accessed March 9, 2013.

OP, opioid peptide.

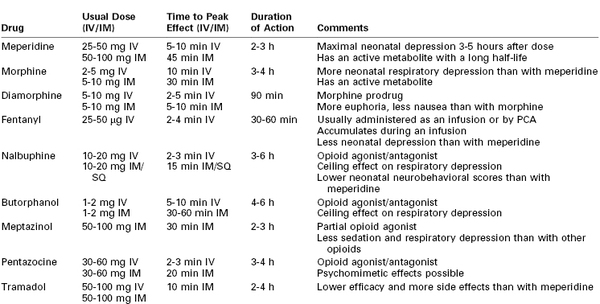

Although systemic opioids have long been used for labor analgesia, there is little scientific evidence to suggest that one drug is superior to another; most often, drug selection is based on local policy or personal preference (Table 22-3). The efficacy of systemic opioid analgesia and the incidence of side effects are largely dose dependent rather than drug dependent.

As a result of their high lipid solubility and low molecular weight (< 500 Da), all opioids readily cross the placenta by diffusion and are associated with the risks of neonatal respiratory depression and neurobehavioral changes. Opioids may also affect the fetus in utero. The fetus and neonate are particularly susceptible to opioid-induced side effects for several reasons. The metabolism and elimination of these drugs are prolonged compared with adults, and the blood-brain barrier is less well developed, allowing for greater central effects. Opioids may result in decreased variability of the fetal heart rate (FHR), although this change usually does not reflect a worsening of fetal oxygenation or acid-base status. The likelihood of neonatal respiratory depression depends on the dose and timing of opioid administration. Even in the absence of obvious neonatal depression at birth, there may be subtle changes in neonatal behavior for several days. Reynolds et al.4 performed a meta-analysis of studies that compared epidural analgesia with systemic opioid analgesia using meperidine, butorphanol, or fentanyl. The authors concluded that lumbar epidural analgesia was associated with improved neonatal acid-base status at delivery. Similarly, in a multicenter randomized trial, Halpern et al.5 compared patient-controlled epidural analgesia using a local anesthetic combined with an opioid to patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) using a parenteral opioid; the investigators demonstrated an increased need for active neonatal resuscitation in the parenteral opioid group (52% versus 31%).

Opioids may be administered as intermittent bolus doses or by PCA. Bolus doses are used more commonly, but the newer synthetic opioids are increasingly used with patient-controlled devices. Because the mode of delivery influences a drug’s pharmacologic profile, the opioids will be discussed by route of administration.

Intermittent Bolus Parenteral Opioid Analgesia

Opioids may be given intermittently by subcutaneous, intramuscular, or intravenous injection. The route and timing of administration influence maternal uptake and placental transfer to the fetus. Subcutaneous and intramuscular routes have the advantage of ease of administration but are painful. Absorption varies with the site of injection and depends on local and regional blood flow; consequently, the onset, quality, and duration of analgesia are highly variable.

Intravenous administration offers several advantages. The onset of analgesia is faster, and the timing and magnitude of the peak plasma concentration of drug are more predictable. It is also possible to titrate dose to effect. For these reasons the intravenous route is generally preferred when available.

Meperidine

In 1947, meperidine (pethidine) became the first synthetic opioid to be used for intrapartum analgesia. More extensively studied than newer drugs, meperidine is the most common opioid given for labor analgesia in the United Kingdom.6 The usual dose is 50 to 100 mg intramuscularly, which can be repeated every 4 hours. The onset of analgesia occurs in 10 to 15 minutes, but 45 minutes may be required to reach peak effect. The duration of action is typically 2 to 3 hours.

Meperidine is highly lipid soluble, readily crosses the placenta, and equilibrates between the maternal and fetal compartments within 6 minutes. Meperidine is metabolized in the liver to produce normeperidine, a pharmacologically active metabolite that is a potent respiratory depressant. Normeperidine also crosses the placenta and is largely responsible for the neonatal side effects encountered with meperidine use.7

Maternal administration of meperidine may reduce fetal aortic blood flow, fetal muscle activity, and FHR variability.7 Sosa et al.8 demonstrated that intravenous meperidine 100 mg, given during the first stage of labor, resulted in an increased incidence of umbilical cord arterial blood acidemia at delivery when compared with a placebo. Normeperidine may result in neonatal respiratory depression. After maternal intramuscular administration of meperidine, the greatest risk for neonatal respiratory depression occurs if meperidine is given to the mother 3 to 5 hours before delivery, whereas the risk is least if it is given within 1 hour before delivery.7 Normeperidine accumulation is associated with altered neonatal behavior, manifesting as reduced duration of wakefulness and attentiveness and impaired breast-feeding.9 Meperidine administration is associated with lower Apgar scores and muscle tone in the neonate. Maternal side effects are of less clinical concern, although there is a high incidence of nausea, vomiting, and dysphoria.

The maternal half-life of meperidine is 2.5 to 3 hours, whereas that of normeperidine is 14 to 21 hours.10 The half-life of both compounds is increased by up to three times in the neonate as a result of reduced clearance.10 Consequently, the adverse effects may be seen in the neonate up to 72 hours after delivery. The action of meperidine is reversed by naloxone; however, the action of normeperidine is not. This is important because antagonism with naloxone may exacerbate normeperidine-induced seizures owing to suppression of the anticonvulsant effect of meperidine.

The quality of labor analgesia with meperidine has been questioned, with some reports indicating that less than 20% of laboring women obtain satisfactory pain relief with its use. The analgesic benefit of intravenous meperidine 50 mg has been observed to be comparable with that of intravenous acetaminophen 1000 mg, but with a greater incidence of adverse effects (64% versus none).11

A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial of intramuscular meperidine 100 mg versus 0.9% normal saline for labor analgesia was terminated after an interim analysis of 50 patients, which revealed a significantly greater reduction in pain scores with meperidine.12 However, the analgesic effect of meperidine was modest, with a median change in visual analog pain scores (VAPS) of 11 mm at 30 minutes; 68% of women required additional analgesia during labor.

The effect of meperidine on the progress of labor is unclear. Historically, meperidine has been given to decrease the length of the first stage of labor in cases of dystocia; however, recent studies have not demonstrated such an effect, and investigators have concluded that meperidine should not be given for this purpose.8

Despite the concerns just highlighted, meperidine continues to be the most common opioid given for labor analgesia worldwide; this is most likely the result of its familiarity, ease of administration, availability, and low cost.

Morphine

Several decades ago, morphine was administered in combination with scopolamine to provide “twilight sleep” during labor and delivery. Analgesia was obtained at the expense of excessive maternal sedation and neonatal depression. Morphine is infrequently used during labor, but it can be given every 4 hours intravenously (0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg) or intramuscularly (0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg), with a peak effect observed in 10 and 30 minutes, respectively. The duration of action when given intravenously or intramuscularly is 3 to 4 hours.10

Morphine is principally metabolized by conjugation in the liver, with up to 70% being transformed into the largely inactive morphine-3-glucuronide. The remainder is transformed into the active metabolite morphine-6-glucuronide, which is 13 times more potent than morphine and has significant analgesic properties.10 Both metabolites are excreted in the urine and have elimination half-lives of up to 4.5 hours in the presence of normal renal function.13 Morphine rapidly crosses the placenta, and a fetal-to-maternal blood concentration ratio of 0.96 is observed at 5 minutes. The elimination half-life of morphine is longer in neonates than in adults.

Maternal side effects include respiratory depression and histamine release, which may result in a rash and pruritus. Like many opioids, morphine is emetogenic and is associated with sedation and dysphoria with increasing doses.10

The greatest neonatal concern is that of respiratory depression. Way et al.14 observed that intramuscular morphine given to newborns caused greater respiratory depression than an equipotent dose of meperidine when response to carbon dioxide was measured. This finding was attributed to an increased permeability of the neonatal brain to morphine.

Pregnancy alters the pharmacokinetics of morphine. Greater plasma clearance, shorter elimination half-life, and earlier peak metabolite levels occur in pregnant women than in nonpregnant women. In theory, these characteristics should reduce fetal exposure. One study observed no cases of neonatal depression after morphine administration during labor, prompting the researchers to suggest that morphine use in labor should be reevaluated.15 Subsequently, Oloffson et. al.16 assessed the analgesic efficacy of intravenous morphine during labor (0.05 mg/kg every third contraction, to a maximum dose of 0.2 mg/kg) and observed clinically insignificant reductions in pain intensity. These investigators also compared intravenous morphine (up to 0.15 mg/kg) with intravenous meperidine (up to 1.5 mg/kg) and found that high pain scores were maintained in both groups despite high levels of maternal sedation.17

Diamorphine

Diamorphine (3,6-diacetylmorphine, heroin) is a synthetic morphine derivative in common use in the United Kingdom, with 34% of obstetric units reporting its use for labor analgesia.6 Diamorphine is twice as potent as morphine. As a prodrug, diamorphine has no direct affinity for opioid receptors, but it is rapidly hydrolyzed by plasma esterases to active metabolites, which are responsible for its clinical effect.10 The metabolite 6-monoacetylmorphine is responsible for a significant proportion of analgesic activity, and it is further metabolized to morphine.13

Typical parenteral doses (intravenous or intramuscular) are 5 to 10 mg. The most common route of administration is intramuscular and results in labor analgesia with a duration of approximately 90 minutes. Both diamorphine and its active metabolite 6-monoacetylmorphine are more lipid soluble than morphine, resulting in a faster onset of analgesia with more euphoria but less nausea and vomiting. These pharmacokinetic properties may also predispose to maternal respiratory depression. Neonatal respiratory depression may also occur due to rapid placental transfer, although this has mainly been reported with high doses.18

Rawal et al.18 investigated the relationship between the dose-delivery interval (following intramuscular administration of a single dose of diamorphine 7.5 mg) and the concentration of free morphine in umbilical cord blood and neonatal outcome. The negative correlation between the dose-delivery interval and umbilical cord blood morphine levels was significant. The correlation between higher free morphine concentrations and lower 1-minute Apgar scores (and the need for neonatal resuscitation) was nonsignificant. Their findings suggest that infants born shortly after interval diamorphine administration are at greater risk for respiratory depression.

Fairlie et al.19 randomized 133 pregnant women to receive intramuscular meperidine 150 mg or diamorphine 7.5 mg and found that significantly more women in the meperidine group reported poor or no pain relief at 60 minutes. However, approximately 40% of women in the two groups requested second-line analgesia, suggesting that both drugs had poor analgesic efficacy. The incidence of maternal sedation was comparable, but vomiting occurred much less frequently and neonatal Apgar scores were higher at 1 minute in the diamorphine group. The trial was small, but the results suggested that at the administered doses, diamorphine conferred some benefit over meperidine with regard to maternal side effects and initial neonatal condition. Currently, a much larger trial of the two drugs, at the same dose and with the same route of administration, is underway in the United Kingdom.

Fentanyl

Fentanyl is a highly lipid-soluble, highly protein-bound synthetic opioid that is highly selective for the µ-opioid receptor, resulting in an analgesic potency 100 times that of morphine and 800 times that of meperidine. Its rapid onset (peak effect, 2 to 4 minutes), short duration of action (30 to 60 minutes), and lack of active metabolites make it attractive for labor analgesia. Although it can be administered intramuscularly, fentanyl is most commonly given intravenously and is titrated to effect; frequently it is administered with a patient-controlled device.

Although small doses of fentanyl undergo rapid redistribution, large or repeated doses may accumulate.10 Importantly, clearance of fentanyl by elimination represents only 20% of that occurring by redistribution, resulting in a rapid increase in context sensitive half-life with an increased duration of infusion.10 Fentanyl has a longer elimination half-life than morphine, but it is metabolized to inactive metabolites in the liver that are excreted in the urine.

Fentanyl readily crosses the placenta; however, the average umbilical vein/maternal vein ratio remains low, most likely owing to a significant degree of maternal protein binding and drug redistribution. In a chronically instrumented sheep model, Craft et al.20 detected fentanyl in fetal plasma as early as 1 minute after maternal administration; however, maternal plasma levels were approximately 2.5 times greater than fetal plasma levels.

Rayburn et al.21 compared responses in women who received intravenous fentanyl (50 to 100 µg as often as once per hour at maternal request) with the experience of women who did not receive analgesia. The mean dose of fentanyl administered was 140 µg (range, 50 to 600 µg). All patients who received fentanyl experienced brief analgesia (mean duration, 45 minutes), sedation, and a transient reduction in FHR variability (30 minutes). There was no difference between groups in neonatal Apgar scores, respiratory status, or Neurologic and Adaptive Capacity Scores (NACS). Rayburn et al.22 also compared intravenous fentanyl (50 to 100 µg every hour) with an equi-analgesic dose of meperidine (25 to 50 mg every 2 to 3 hours). The researchers observed less sedation, vomiting, and neonatal naloxone administration with fentanyl, but they observed no difference between groups in NACS. The two groups had similarly high pain scores, suggesting that both drugs have poor analgesic efficacy.

Nalbuphine

Nalbuphine is a mixed agonist-antagonist opioid analgesic with agonist activity at κ-opioid receptors, thereby producing analgesia, and partial agonist activity at µ-opioid receptors, thus resulting in less respiratory depression.13 A partial agonist is a drug that has receptor affinity but produces a submaximal effect compared with a full agonist, even when given at very high doses.10

Nalbuphine can be administered by intramuscular, intravenous, or subcutaneous injection, with a usual dose of 10 to 20 mg every 4 to 6 hours. The onset of analgesia occurs within 2 to 3 minutes of intravenous administration and within 15 minutes of intramuscular or subcutaneous administration. The drug is metabolized in the liver to inactive compounds that are then secreted into bile and excreted in feces.13

Nalbuphine and morphine are of equal analgesic potency and result in sedation and respiratory depression at similar doses. However, because of its mixed receptor affinity, nalbuphine demonstrates a ceiling effect for respiratory depression at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg.13 Nalbuphine causes less nausea, vomiting, and dysphoria than morphine. Concerns that it may have an antianalgesic effect, particularly in men, led to the withdrawal of nalbuphine in the United Kingdom in 2003.13

Wilson et al.23 performed a randomized, double-blind comparison of intramuscular nalbuphine 20 mg and meperidine 100 mg for labor analgesia. Nalbuphine was associated with less nausea and vomiting but more maternal sedation. Analgesia was comparable between the groups. Neonatal neurobehavioral scores were lower in the nalbuphine group at 2 to 4 hours, but there was no difference between groups at 24 hours. The umbilical vein-to-maternal vein concentration ratio was higher with nalbuphine (mean ± SEM, 0.78 ± 0.03) than with meperidine (0.61 ± 0.02). A subsequent study failed to demonstrate an analgesic advantage with either drug but again reported transient neonatal neurologic depression with nalbuphine.24

Amin et al.25 compared the neonatal outcome for women who received either nalbuphine or saline-control before elective cesarean delivery. They found lower 1-minute Apgar scores and a significantly longer time to sustained respiration in the nalbuphine group. However, 5-minute Apgar scores and umbilical cord blood gas measurements were similar between groups.

Nicolle et al.26 evaluated the transplacental transfer and neonatal pharmacokinetics of nalbuphine in 28 women who received the drug either intramuscularly or intravenously during labor. The investigators found a high umbilical vein-to-maternal vein concentration ratio of 0.74, which did not correlate with the administered dose. The estimated neonatal half-life was 4.1 hours, which is greater than the adult half-life and, more importantly, longer than the half-life of naloxone. There was a transient reduction in FHR variability in 54% of the fetuses, which was not associated with the plasma concentration of nalbuphine. Analgesia was rated as effective by 54% of parturients.

Giannina et al.27 compared the effects of intravenous nalbuphine and meperidine on intrapartum FHR tracings. Nalbuphine significantly reduced both the number of FHR accelerations and FHR variability, whereas meperidine had little effect.

A recent prospective pilot study of 302 nulliparous parturients (57 women who received nalbuphine, and a control group of 245 women who received neither nalbuphine nor epidural analgesia) reported a marked reduction in duration of the active phase of the first stage of labor in the nalbuphine group (75 minutes versus 160 minutes in the control group); this effect appeared to be independent of oxytocin use.28 Additional investigations are needed to verify this finding.

Butorphanol

Butorphanol is an opioid with agonist-antagonist properties that resemble those of nalbuphine. It is 5 times as potent as morphine and 40 times more potent than meperidine.29 The typical dose during labor is 1 to 2 mg intravenously or intramuscularly. Butorphanol is 95% metabolized in the liver to inactive metabolites. Excretion is primarily renal. A plateau effect for respiratory depression is noted, where butorphanol 2 mg produces respiratory depression similar to that of morphine 10 mg or meperidine 70 mg. However, butorphanol 4 mg results in less respiratory depression than morphine 20 mg or meperidine 140 mg.29

Maduska and Hajghassemali30 compared intramuscular butorphanol (1 to 2 mg) with meperidine (40 to 80 mg) and found similar efficacy of labor analgesia. Butorphanol and meperidine exhibited rapid placental transfer with similar umbilical vein-to-maternal vein concentration ratios (0.84 and 0.89, respectively) and no differences in FHR tracings, Apgar scores, time to sustained respiration, or umbilical cord blood gas measurements at delivery.

Hodgkinson et al.31 performed a similar study comparing the intravenous administration of butorphanol (1 or 2 mg) and meperidine (40 or 80 mg) for labor analgesia. Maternal pain relief was found to be adequate and comparable, but there were fewer maternal side effects (e.g., nausea, vomiting, dizziness) in the women who received butorphanol. There was no difference between groups in neonatal Apgar or neurobehavioral scores.

Conversely, in a double-blind comparison of intravenous butorphanol (1 or 2 mg) and meperidine (40 or 80 mg) during labor, Quilligan et al.32 noted lower pain scores at 30 minutes and 1 hour after the administration of butorphanol. There was no significant difference in Apgar scores between the two groups of infants; however, the mean FHR was noted to be higher among those fetuses whose mothers received butorphanol.

Nelson and Eisenach33 investigated the possible synergistic effect of giving both intravenous butorphanol and meperidine; they compared the administration of both drugs with the administration of either drug alone. Women received intravenous butorphanol 1 mg, meperidine 50 mg, or butorphanol 0.5 mg with meperidine 25 mg. All three groups reported a similar reduction in pain intensity; however, only 29% of the women achieved clinically significant pain relief. There was no difference among groups in maternal side effects or neonatal Apgar scores. The investigators concluded that there was no therapeutic benefit to combining the two drugs.

Atkinson et al.34 performed a double-blind trial of intravenous butorphanol (1 to 2 mg) and fentanyl (50 to 100 µg) administered hourly on maternal request. The investigators found that butorphanol provided better analgesia initially, with fewer requests for additional drug doses or progression to epidural analgesia. There was no difference in adverse maternal or neonatal effects between the two groups.

Meptazinol

Meptazinol is a partial opioid agonist specific to µ-opioid receptors with a rapid onset of action (i.e., 15 minutes after intramuscular administration). The intramuscular dose (50 to 100 mg) and duration of action for labor analgesia are similar to those for meperidine. Its partial agonist activity is thought to result in less sedation, respiratory depression, and risk for dependence than occurs with other opioid agonists.

Meptazinol is metabolized by glucuronidation in the liver and then excreted in the urine. This process is more mature in the neonate than is the metabolic pathway of meperidine. The adult half-life is 2.2 hours, and the neonatal half-life is 3.4 hours.35

Theoretically, this rapid elimination should confer a lower incidence of adverse neonatal effects than occurs with meperidine. In a single-blind study, Jackson and Robson36 compared intramuscular meptazinol with meperidine at the same doses (100 mg if maternal weight was ≤ 60 kg, 125 mg if 61 to 70 kg, and 150 mg if ≥ 70 kg). Meptazinol provided significantly better analgesia than meperidine but resulted in a similar frequency of maternal side effects.

Nicholas and Robson37 subsequently compared intramuscular meptazinol 100 mg with meperidine 100 mg in a randomized, double-blind trial in 358 parturients. Meptazinol provided significantly better pain relief at 45 and 60 minutes, but the two drugs provided a similar duration of analgesia, and there was no significant difference between groups in maternal side effects. Neonatal outcomes were similar between groups, except significantly more infants whose mothers had received meptazinol had an Apgar score of 8 or higher at 1 minute.

Other investigators have reported little difference in analgesic efficacy, maternal side effects, or neonatal outcomes between meptazinol and meperidine. In a study of 1100 patients, Morrison et al.38 found that neither drug given at equal doses (150 mg in patients weighing > 70 kg, 100 mg in those weighing ≤ 70 kg) was effective at relieving pain. Maternal drowsiness was significantly less pronounced with meptazinol, but the incidence of vomiting was higher. FHR changes and neonatal outcomes, including Apgar scores, need for resuscitation, and suckling ability, were comparable. The overall use of naloxone was similar in the two groups, but if the dose-delivery interval exceeded 180 minutes, significantly more neonates in the meperidine group required naloxone.

De Boer et al.39 assessed neonatal blood gas and acid-base measurements after maternal intramuscular administration of meptazinol (1.5 mg/kg) or meperidine (1.5 mg/kg) during labor. Capillary blood gas measurements at 10 minutes of life showed a significantly lower pH and a higher PaCO2 in the meperidine group, although this difference resolved by 60 minutes. These findings suggest that meptazinol causes less neonatal respiratory depression.

Meptazinol may confer some benefits over meperidine in early neonatal outcome, but it is not widely used. A recent survey indicated that it is the intramuscular labor analgesic of choice in only 14% of obstetric units in the United Kingdom.6 The cost of meptazinol is considerably higher than that of meperidine. Meptazinol is not available in the United States.

Pentazocine

Pentazocine is a selective κ-opioid receptor agonist with some weak antagonist activity at µ-opioid receptors.13 It may be given orally or systemically by intramuscular or intravenous injection. The typical parenteral adult dose is 30 to 60 mg, which is equivalent to morphine 10 mg. Onset of action occurs within 2 minutes when given intravenously and within 20 minutes if given by the intramuscular route. Metabolism occurs in the liver by oxidation and glucuronidation; metabolites are then excreted in the urine.

Pentazocine causes similar respiratory depression to that seen with equipotent doses of morphine and meperidine, but it exhibits a ceiling effect with doses in excess of 60 mg. Psychomimetic effects (e.g., dysphoria, hallucinations) may complicate its use, particularly with increasing doses.

In a double-blind study of 94 laboring women who received intramuscular administration of pentazocine (up to 60 mg) and meperidine (up to 150 mg), Mowat and Garrey40 observed equivalent and adequate analgesia for approximately 40% of women in each group. The incidence of sedation was comparable between groups, and fewer women in the pentazocine group complained of nausea and vomiting.

In a randomized study comparing intramuscular administration of pentazocine 30 mg with tramadol 100 mg in 100 laboring women, Kuti et al.41 observed greater analgesia in the pentazocine group at 1 hour, with a longer time to subsequent request for additional analgesia (181 minutes versus 113 minutes, P < .05). The overall analgesic effect of both drugs was modest, with only 30% to 50% of women reporting satisfactory pain relief. More women in the pentazocine group were drowsy, but the result did not achieve statistical significance. There were no cases of maternal respiratory depression, and there was no difference between groups in neonatal outcomes. The investigators concluded that pentazocine provides better labor analgesia than tramadol.

Tramadol

Tramadol is an atypical, weak, synthetic opioid that has affinity for all opioid receptors, but particularly the µ-opioid subtype. Tramadol also inhibits neuronal reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin, and it directly stimulates presynaptic serotonin release, which may account for some of its analgesic effects.13 Tramadol can be administered orally or by intramuscular or intravenous injection at a dose of 50 to 100 mg every 4 to 6 hours in adults. Although the initial bioavailability after oral administration is only 70% owing to a significant first-pass effect, this increases to almost 100% with repeated doses.10,13

The analgesic potency of tramadol is equal to that of meperidine and one fifth to one tenth that of morphine. In equi-analgesic doses, tramadol causes less respiratory depression than morphine; at usual doses, no clinically significant respiratory depression occurs. The onset of analgesia is within 10 minutes of intramuscular administration, with an effective duration of 2 to 4 hours. Tramadol is metabolized by demethylation and glucuronidation in the liver to several metabolites, one of which has independent analgesic activity (M1). The metabolites are almost entirely excreted in the urine. The elimination half-life is 5 to 6 hours, whereas that of the active metabolite is 9 hours.

Tramadol readily crosses the placenta, and an umbilical vein-to-maternal vein ratio of 0.94 has been observed at delivery.42 Neonates possess complete hepatic capacity for metabolism of tramadol to its active metabolite M1. The elimination profile of M1 suggests a terminal half-life of 85 hours because of its requirement for renal elimination, which is an immature process in neonates. Claahsen-van der Grinten et al.42 reported that intrapartum tramadol (initial dose of 100 mg, then subsequent doses of 50 to 100 mg, up to a maximum dose of 250 mg) resulted in normal Apgar scores and NACS, with no correlation to tramadol or M1 concentrations. However, the single neonate who required naloxone had the highest plasma concentration of tramadol.

The analgesic efficacy of tramadol in labor has been questioned. Keskin et al.43 compared intramuscular tramadol 100 mg and meperidine 100 mg for labor analgesia; they observed greater pain relief and a lower incidence of nausea and fatigue with meperidine. There was no significant difference between groups in neonatal outcome, but more infants in the tramadol group required supplemental oxygen for respiratory distress and hypoxemia. The investigators concluded that meperidine provided superior analgesia and was associated with a better side-effect profile.

By contrast, Viegas et al.44 conducted a randomized, double-blind trial to compare intramuscular administration of tramadol 50 mg, tramadol 100 mg, and meperidine 75 mg during labor. Tramadol 100 mg and meperidine 75 mg provided similar labor analgesia; however, a higher incidence of maternal and neonatal adverse effects was observed with meperidine.

Kooshideh and Shahriari45 evaluated the intramuscular administration of tramadol 100 mg or meperidine 50 mg on labor duration and analgesic efficacy in 160 parturients. The investigators observed that tramadol was associated with a reduced duration of both the first stage (140 versus 190 minutes, P < .001) and the second stage of labor (25 versus 33 minutes, P = .001). There was no difference in median and maximum pain scores between groups 1 hour after drug administration; however, lower pain scores were observed during the second stage of labor in the meperidine group. Nausea, vomiting, and drowsiness occurred less frequently in the tramadol group.

Patient-Controlled Analgesia

Patient-controlled analgesia has been used to control postoperative pain for several decades and for the provision of labor analgesia in more recent years. First described in women with thrombocytopenia who were unable to undergo a neuraxial analgesia procedure, its use has grown in availability and popularity. A 2007 survey demonstrated that 49% of obstetric units in the United Kingdom offered PCA for labor analgesia.46 Purported advantages of PCA include (1) superior pain relief with lower doses of drug, (2) less risk for maternal respiratory depression compared with bolus intravenous administration, (3) less placental transfer of drug, (4) less need for antiemetic agents, and (5) greater patient satisfaction.47 The smaller, more frequent dosing used with this mode of analgesia may result in a more stable plasma drug concentration and a more consistent analgesic effect when compared with that of intermittent bolus administration regimens.47

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree