On successfully completing this topic, you will be able to:

discuss the indications for symphysiotomy

understand the technique

understand the role of destructive operations

understand the procedures involved in destructive operations.

Introduction

Symphysiotomy

Symphysiotomy is a relatively common procedure in the developing world, where it is used in situations of cephalopelvic disproportion when CS is not available. Symphysiotomy leaves no uterine scar and subsequent risk of ruptured uterus in future labours is not increased. Van Roosmalen illustrated the potential morbidity and mortality of caesarean sections carried out in developing country rural hospitals. Mortalities of up to 5% and an incidence of uterine scar rupture in subsequent pregnancies of up to 6.8% have been reported. Symphysiotomy has a low maternal mortality, with three deaths reported in a series of 1752 symphysiotomies. All three deaths were unrelated to the procedure.

Hartfield reviewed the cases of 138 women in whom symphysiotomy had been performed.1 Early and late complications were few and rarely serious, if recommended guidelines were followed. He also reviewed published series of women followed up, for two years or more, after symphysiotomy and concluded that permanent major orthopaedic disability only occurs in 1–2% of cases.2

Pape carried out a prospective review of 27 symphysiotomies performed between 1992 and 1994.3 Five women had paraurethral tears needing suturing, nine had oedema of the vulva or haematomas tracking from the symphysiotomy. All made a full recovery and severe pelvic pain was not a feature in any woman.

In 2001, the question of legal action against obstetricians in Ireland who carried out symphysiotomies was raised.4 Verkuyl made the point that many symphysiotomies were performed in Roman Catholic countries because contraception was illegal, even for medical reasons, and women were spared repeated operative deliveries.5

Symphysiotomy is a useful technique that is occasionally required in UK practice. One report highlighted four cases where it has been used successfully in the UK.

Björkland published a comprehensive retrospective review of the literature based on papers published between 1900 and 1999; 5000 symphysiotomies and 1200 CS operations were included and the results indicated that symphysiotomy is safe for the mother and life saving for the child.6 Severe complications are rare.

Destructive procedures

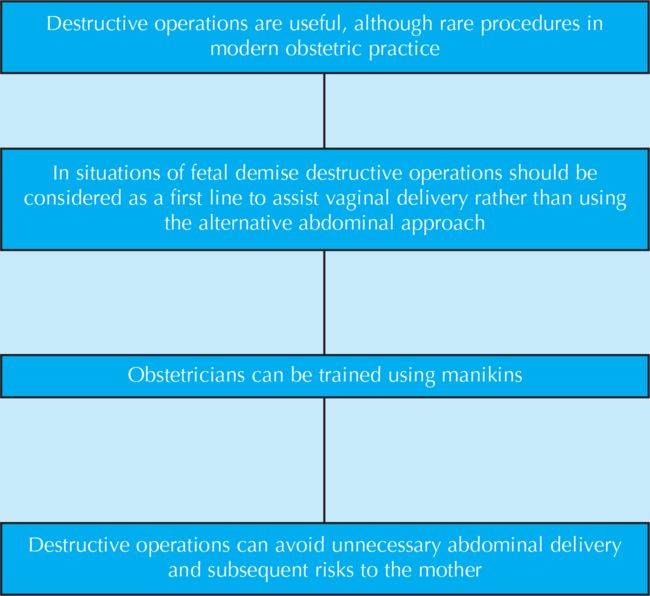

Destructive operations are also relatively common in the developing world in cases of obstructed labour, where absent prenatal care and poor intrapartum care at peripheral hospitals have resulted in fetal demise. Reported incidences range between 0.094% and 0.98% of all deliveries. A destructive procedure is an alternative to abdominal delivery that may carry considerable risk to the mother.

With the use of prophylactic antibiotics and thromboprophylaxis, CS has become safer and there is only a limited role in modern practice for destructive procedures in the developed world.

Symphysiotomy

Indications

Trapped aftercoming head of breech due to cephalopelvic disproportion.

Severe cases of shoulder dystocia that do not resolve with routine manoeuvres.

In cases of cephalopelvic disproportion with a vertex presentation and a living fetus (in the developing world), when at least two-thirds of the fetal head has entered the pelvic brim; note that the use of forceps is contraindicated.

In cases of cephalopelvic disproportion with a vertex presentation, when CS is declined by the mother.

Technique

1 Place the woman in the lithotomy position, with her legs supported by two assistants. The angle between the legs should never be more than 60–80° to avoid putting a strain on the sacroiliac joints and tearing the urethra and/or bladder.

2 Inject local anaesthetic into the skin and symphysis pubis. This step identifies the joint space and the needle can be left in place as a guide wire if the joint has been difficult to locate.

4 Push the catheter (and urethra) aside with the index and middle fingers of the left hand in the vagina. The index finger pushes the catheter and urethra to the woman’s right side and the middle finger remains on the posterior aspect of the pubic joint in the midline to monitor the action of the scalpel.

5 Incise the symphysis pubis in the midline, at the junction of the upper and middle thirds. Use the upper third of the uncut symphysis as a fulcrum against which to lever the scalpel to incise the lower two-thirds of the symphysis. Cut down through the cartilage until the pressure of the scalpel blade is felt near the middle finger in the vagina.

6 Remove the scalpel and rotate it through 180° and the remaining upper third of the symphysis is cut. If a solid-bladed scalpel is available, this is better. If not, take great care with the replaceable standard scalpel blade, which is much sharper. The symphysis is cut through very easily; beware of going deeper and injuring the vagina or bladder or the operator’s finger.

7 Once the incision is made, pinch it between finger and thumb and the symphysis should open as wide as the operator’s thumb.

8 After this separation of the cartilage, remove the catheter to decrease urethral trauma.

9 Use a large episiotomy to relieve tension on the anterior vaginal wall.

10 After delivery of the baby and placenta, compress the symphysis between the thumb above and index and middle fingers below for some minutes, to express blood clots and promote haemostasis.

11 Re-catheterise and leave a urinary catheter in place for 5 days.

Destructive procedures

Destructive operations may be required where the fetus is dead and where a vaginal delivery is being attempted. It may be the appropriate method for delivery to minimise maternal risk, or it may be the only route by which the mother wishes to be delivered. Whenever a destructive procedure is being considered, it must only be performed with the mother’s consent.

1 Initially, basic resuscitation must be carried out quickly, to avoid undue delay in delivering a dead fetus.

2 Catheterise.

3 Since urinary and genital tract infections are common, antibiotic prophylaxis should be used.

5 The cervix should be fully dilated, although destructive surgery may be performed, by an experienced operator, when the cervix is dilated by 7 cm or more.

6 The genital tract and rectum must be carefully examined after the procedure.

7 A catheter should be left in place for at least 48 hours.

The three most common destructive procedures are:

craniotomy

perforation of the aftercoming head

decapitation.

Craniotomy

Indications

Craniotomy is indicated for the delivery of a dead fetus in situations of cephalopelvic disproportion and hydrocephalus.

Method

1 The fetal head should be no more than three-fifths above the pelvic brim, except in cases of hydrocephalus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree