On successfully completing this topic, you will be able to:

appreciate the risks posed to the pregnant women by anaesthetic drugs and techniques

understand anaesthetic emergency problems affecting the pregnant woman.

Introduction and incidence

The proportion of women dying from complications of anaesthetics has declined markedly over the last 20 years. Deaths from airway-related problems have declined over the last ten years of Confidential Enquiry reports, but failure to ventilate the lungs is still a major concern. The risk of death from an obstetric general anaesthetic has been estimated at one in 20 000. In 2011, a large series of obstetric patients in Canada undergoing general anaesthesia confirmed that difficult intubation still occurs in 3.3% (range 1.3–16.3%) and failed intubation in one in 250 patients. The events occur almost exclusively in emergency cases and are associated with the most urgent of cases, inexperienced staff and failure to follow standard practice. Box 38.1 indicated the problems highlighted by the Confidential Enquiry reports. However improved assessment and anticipation of airway problems has led to series with fewer failed intubations.

Airway management especially in the obese:

the danger of unrecognised oesophageal intubation and the importance of always using a capnograph to confirm tracheal placement

inadequate use of intraoperative and postoperative monitoring

the need for the proper checking of anaesthetic machines

the need for staff to possess advanced life-support skills

the need for staff to able to manage bronchospasm and anaphylaxis

the contribution of isolated sites in delaying the provision of senior help and of blood products.

Other ways in which anaesthesia in some way contributed to maternal deaths include:

issues of timely and effective communication and consultation

failures to appreciate the severity of maternal illness

inadequate usage of invasive monitoring

substandard care in women who have sepsis, pre-eclampsia and haemorrhage.

Difficult intubations – prevention better than cure

Preparation for an intubation

1 Appropriately trained staff – anaesthetist and assistant.

2 Correct equipment checked and available to hand, including airway adjuncts for difficult airways.

3 Position of the woman optimised.

Using the 25° ’back up’/ramp position makes it easier to intubate obese pregnant women and should always be used. It may be useful to employ a specific pillow that allows the obese women to be placed in the best position.

Management of failed intubation or ventilation is a core skill that should be rehearsed and practised regularly. Obstetricians should be involved in this training and need to understand how they can help. There should be an appreciation of the implications for decision-making regarding delivery. The drill for managing this situation must be clear and simple and the one offered here is based on the Difficult Airway Society guidelines.1

In Algorithm 38.1 for failed intubation, points which particularly apply to the obstetrician are highlighted in bold print.

It is important that the anaesthetist does not get fixated with intubating the trachea, since in these circumstances the goal remains oxygenating the lungs by whatever technique available. Case reports show that the Proseal® laryngeal mask airway has been commonly used since 2003 to obtain enough successful airway control to allow ventilation. This is a type of laryngeal mask airway that has a drainage channel, which allows early identification and drainage of regurgitated gastric contents.

A major patient management matter at the time of failed intubation is a joint assessment between obstetrician and anaesthetist about the degree of urgency of the operation and the degree of need to continue with general anaesthesia for the operation.

Other complications

Premature extubation

This problem is associated with aspiration of gastric contents and hypoxia. The woman must be fully awake, able to breathe adequately and to protect her airway, before the endotracheal tube is removed. The anaesthetist will decide whether to extubate in the left lateral or sitting position. It is advisable to leave all monitoring attached until the extubation has been successfully achieved. Potential hazards include laryngospasm on extubation. There should be early recourse to rapid reintubation rather than struggling to break the spasm. Drugs, equipment and personnel should be instantly available should this occur while still in the operating theatre.

Outside the operating theatre, mortality reports have highlighted respiratory deaths related to incorrect administration and supervision of patients receiving opioids, and respiratory failure from the delayed effects of neuromuscular blockade.

Awareness

The situation where the patient is not completely unconscious during an operation, when they were expected to be, has been particularly associated with obstetric general anaesthesia. Incidence is 0.26%; approximately double that of the nonobstetric population. Delay in intubation after a minimal dose of anaesthetic induction agent but with a muscle relaxant may lead to patient recall of the intubation. Conscious awareness with pain at the time of incision and delivery is associated with the practice of not giving opiate until after the delivery, using less than 65% nitrous oxide in oxygen and not giving adequate inhaled anaesthetic, either because of concern about the relaxant effects on the uterus with subsequent increased blood loss or because of human error.

Patient reports of awareness must always be taken seriously and reported to the anaesthetist for investigation and management, with the aim of avoiding the patient developing a post-traumatic stress disorder.

Regional blocks (epidural and spinal anaesthesia and analgesia)

The spinal cord leaves the skull within the dural tube, bathed in CSF and terminates in adults at approximately the first or second lumbar interspace.

The dural tube and CSF continue down into the upper part of the sacrum.

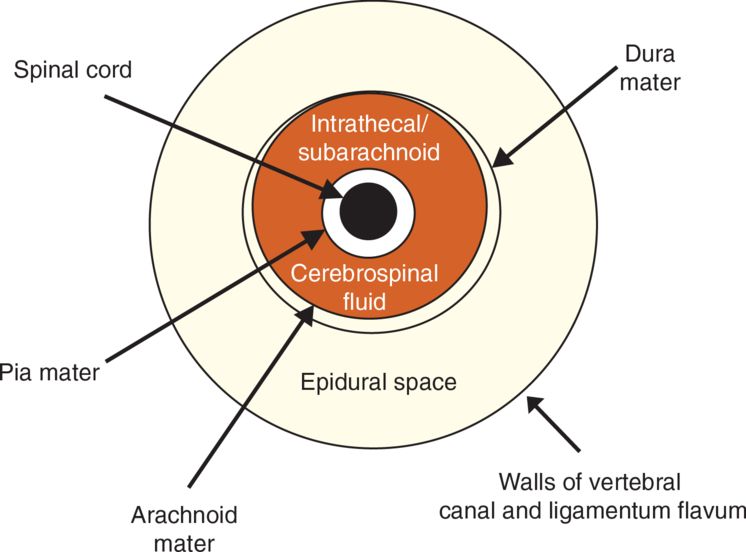

The epidural space is a ‘potential’ space that extends from the base of the skull to the sacral hiatus and contains nerve roots, fat and blood vessels. As the nerves cross the epidural space, they make connections with the sympathetic trunk before exiting laterally through the transverse foramina.

Inside the vertebral column, the dura mater is the anatomical boundary that divides the two kinds of blocks (Figure 38.1). Injection of drugs inside the dura mater is variously called a ‘spinal’, ‘subarachnoid’ or an ‘intrathecal’ block. Injection of drugs outside the dura is called an epidural or extradural block.

Pain relief for labour requires sensory blockade T10–L1 (first stage) and S2, S3, S4 (second stage). Anaesthesia for CS requires motor and sensory blockade from T4 to S5.

A ‘nerve’ block refers to block of a single nerve e.g. pudendal whereas a ‘regional’ block refers to groups of nerves, as happens with a spinal or epidural injection.

During a spinal block, a small volume of concentrated drug(s) spreads rapidly within the CSF. The effect of the local anaesthetic is to block transmission of impulses along the nerves. The onset of the block is rapid because the nerves have no covering.

When local anaesthetic drugs are injected into the epidural space, the volumes of drugs required are very much greater as the volume of the space is larger. In addition the onset of effect is slower because the nerves, as they cross the epidural space, have acquired a covering of dura.

Characteristics of spinal and epidural anaesthetics

Epidural anaesthesia is conventionally used for analgesia for labour and vaginal delivery or anaesthesia for operative delivery. Conventionally, an ‘epidural’ refers to the placement of an epidural catheter in the epidural space so that drug can be repeatedly added to the space, or continuously infused to give analgesia for the duration of labour, irrespective of how long that is.

Epidurals are not reliably influenced by gravity or positioning and always involve larger volumes of drugs.

Occasionally, a spinal injection may be used as a method of analgesia for labour, for speed and then an epidural catheter is used for the rest of the labour. This is called combined spinal/epidural analgesia (CSE).

Spinal anaesthesia is usually used for obstetric surgery. A ‘spinal’ refers to a one-off injection into the intrathecal space. The effect lasts for about 2 hours, which is long enough to carry out a CS. Intrathecal infusions are not conventionally used in obstetric practice.

Epidural incremental top-ups were used more routinely for anaesthesia for CS in the past, and may still be indicated in certain patients where a slow onset of anaesthesia is desirable e.g. severe cardiac disease. For emergency caesarean sections or other operative procedures, such as retained placenta, existing epidurals can be topped up or spinal anaesthesia given. A combined spinal/epidural anaesthetic may be used for operative obstetrics, especially when the operation is expected to be prolonged, or the intention is to use the epidural catheter to deliver postoperative analgesia.

A single-shot spinal injection is expected to result in a dense, complete (no ‘missed’ – unanaesthetised – dermatome segments) block of rapid onset. Its downside is that it causes marked vasodilatation (owing to the effect of local anaesthetic on the thoracic and lumbar sympathetic nerves) with consequent hypotension. This predictable problem is managed with vasopressors such as phenylephrine or ephedrine. The height of the block is somewhat unpredictable and uncontrollable, but is a function of dose and patient positioning.

The desired height of block for CS is to the T2–T4 level (sternal angle of Louis). If the block is not high enough, the patient will feel pain from traction of the peritoneum that is supplied by the lesser splanchnic nerve; but above this level a spinal is described as ‘high’ and can cause cardiovascular and respiratory problems (see below).

When using ‘heavy’, i.e. hyperbaric (heavier than CSF) local anaesthetic as is used for spinals, the position of the woman affects where the local anaesthetic lies and can be used to influence the height of the block. A block that has not reached the required height can be brought higher by placing the woman in the head-down position. Similarly, a high spinal can be stopped from going higher by placing the woman head up. Gravity can be made to influence the height of the block for up to 20 minutes after the injection. Pillows under the shoulders and head virtually eliminate the spread of a spinal dose beyond the thoracic level.

Dosage calculation

Bupivacaine 0.5% contains 5 mg/ml; 10 ml therefore contains 50 mg. The calculation is as follows: 0.5% means 0.5 g in 100 ml (equivalent to 500 mg in 100 ml; divide by 100 to get 5 mg in 1 ml).

Levobupivacaine is the L-isomer of bupivacaine. It has similar properties, but is thought to have lower cardiovascular toxicity when injected accidentally intravenously. There has been a move towards using this preparation but bupivacaine is also used. The dose is the same for both isomers.

Ropivacaine is a newer local anaesthetic and also has improved safety with regard to cardiovascular complications.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree