15.1 Suspected heart disease

assessment

Assessment

Pulses

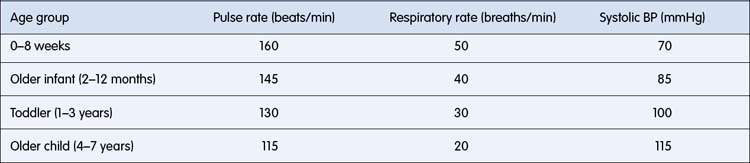

Examination of pulses should include both left and right arms and femoral pulses. The upper and lower limb pulses are best compared when palpated simultaneously. Relatively reduced lower-limb pulses suggest coarctation, but femoral pulses may be difficult to feel in the first few days of life. Bounding pulses due to a wide pulse pressure may be associated with patent ductus arteriosus, significant aortic regurgitation, and high cardiac output states. The physiological increase in heart rate in children varies markedly with activity and so it is the resting rate that should be noted (Table 15.1.1).

Auscultatory findings

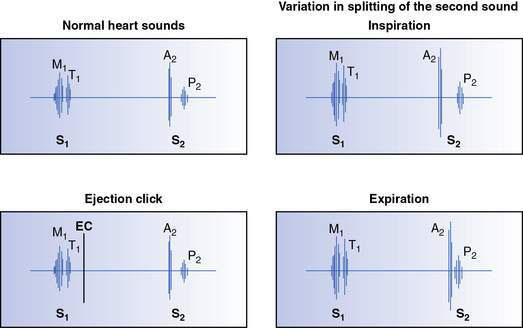

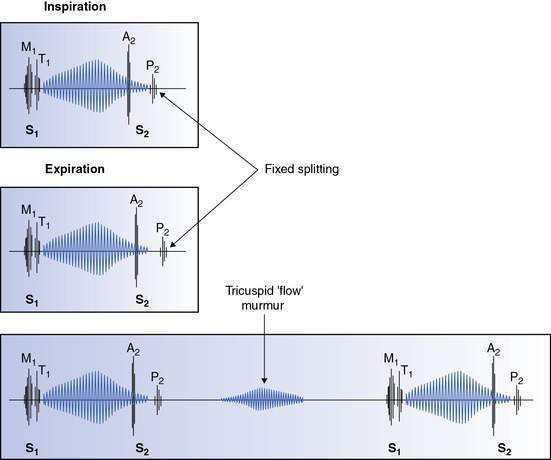

Splitting of the second heart sound should be noted (Fig. 15.1.1). Splitting is widened during inspiration. Fixed splitting, a feature of atrial septal defect, implies absence of variation between inspiration and expiration (Fig. 15.1.2) and is also typically widely split.

Fig. 15.1.1 Illustration of normal heart sounds, normal splitting of the second sound and ejection click (EC).

Fig. 15.1.2 Auscultatory signs associated with an atrial septal defect showing ejection systolic murmur, fixed splitting of S2 and tricuspid flow murmur (see Chapter 15.2).

Accentuation of the pulmonary component of the second sound tends to be associated with a loud second sound, which may be palpable, often with no definite splitting, and implies the presence of pulmonary hypertension. However, it should be noted that the normal aortic closure sound may be loud in children with a thin chest wall and is sometimes palpable at the upper left sternal border. The presence of an ejection click (see Fig. 15.1.1) is a useful ancillary auscultatory finding. Such sounds are heard shortly after the first heart sound and tend to be high-frequency and discrete in character. If heard at the apex, it usually implies a bicuspid aortic valve or aortic valve stenosis. When originating from the pulmonary valve, it is heard at the left sternal edge and varies with respiration, being louder on expiration. This finding is characteristic of pulmonary valve stenosis.

Murmurs

The following features of the murmur should be determined:

Amplitude

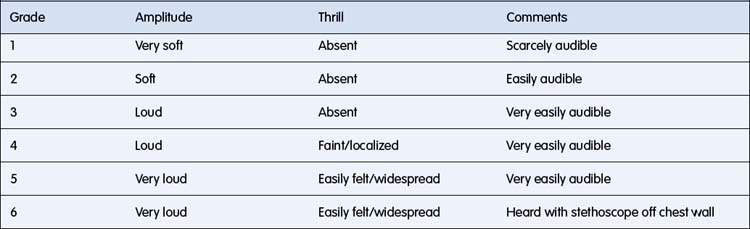

Murmurs may be graded according to the scale in Table 15.1.2. The amplitude of the murmur is affected by the thickness of the chest wall, and the direction, volume and velocity of blood flow relative to the stethoscope position.

Characterization

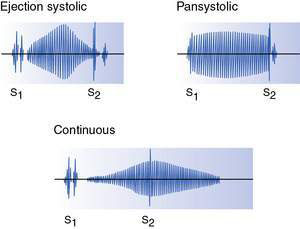

Ejection murmurs (Fig. 15.1.3) are systolic and crescendo–decrescendo in character, starting shortly after the first sound. Good examples are the murmurs of pulmonary or aortic valve stenosis.

Pansystolic murmurs (Fig. 15.1.3) are murmurs that commence at the first sound and continue to the second sound. They may be due to atrioventricular valve incompetence (e.g. mitral incompetence) or a ventricular septal defect (VSD).

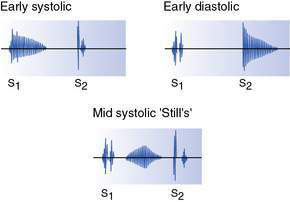

Diastolic murmurs may be early diastolic (see Fig. 15.1.4) (commencing at the second sound) or mid-diastolic (see Fig. 15.1.2). The former reflect either aortic or pulmonary incompetence, whereas mid-diastolic murmurs occur during ventricular filling and reflect either stenosis of or increased blood flow through an atrioventricular valve (e.g. mitral stenosis or secondary to a large left–right shunt due to a VSD).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree