Controversies Surrounding Pediatric Psychopharmacology

The past several decades have witnessed an increased awareness of mental health disorders and neurobehavioral problems in children [1]. These behavioral issues now represent a growing portion of pediatric visits. Addressing and appropriately managing early-onset disorders may improve quality of life while providing hope that adult morbidity may be attenuated [2]. Given the shortage of mental health providers and the concept of the pediatric practice as “medical home,” many pediatricians are poised to receive this population. Caring for this population of children is riddled with systemic obstacles. Lack of time, training, support, and compensation, together with poor integration of collaboration with mental health resources, all contribute to this challenge. Children’s mental health has become a priority issue for the American Academy of Pediatrics [3].

A better understanding of the magnitude of mental health issues facing children was highlighted by the recently completed National Comorbidity Study, which examined the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a sample of more than 10,000 children between the ages of 13 and 18 years. The investigators found that almost 50% of adolescents would have had enough symptoms at some point in their life to meet criteria for a psychiatric disorder by 18 years of age [1]. Twenty-two percent were found to have significant impairment as a result of their symptomatology. These numbers are alarming. The fact that there are fewer than 8000 child psychiatrists and fewer than 600 developmental behavioral pediatricians in the United States to care for these children highlights the tremendous shortage of subspecialty providers, and compounds the problem of providing adequate care.

In response to the imbalance between the number of patients and providers, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee of Psychosocial Aspect of Child and Family Health and Task Force on Mental Health has set a goal for pediatricians to be competent in the use of medications to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), major depressive disorder, and anxiety [4]. The AAP has created several valuable tools in the area of mental health (Addressing Mental Health Concerns in Primary Care: A Clinician’s Toolkit, Autism Toolkit, ADHD Toolkit) to support pediatricians in assessment, decision-making, management, coding, and so forth, and these are now available for purchase. These tools are helpful, but it will be important for clinicians to familiarize themselves with current research and the medications used to treat these common problems.

The National Comorbidity Study found that the top 3 pediatric mental health disorders in decreasing frequency are anxiety (specific phobia at 19.3%, social phobia at 9.1%), depression (11.7%), and ADHD (8.7%). This finding is consistent with previous studies [5,6]. Although autism is not considered among the most common disorders (frequency of 1:110) [7], it is considered to be the fastest-growing developmental disability [8]. Therefore, autism and its pharmacotherapy are also described in this article.

Empirically driven treatment models

Management of many common disorders in medicine often relies on treatment models that are based on a comprehensive base of research and observed clinical outcomes in adult patients. Until recently, most medication interventions in pediatric mental health were extrapolated from adult treatment patterns and used in an off-label fashion [9,10]. However, research over the past two decades has led to the emergence of pediatric-specific practice parameters for several common conditions, including some neurobehavioral disorders. Psychopharmacologic agents are now being used with greater frequency than ever before. The use of second-generation antipsychotics has more than doubled in the past decade [11,13]. Almost one-third of psychotropic medications are prescribed by non–mental health providers [14].

Anxiety

The Surgeon General estimates that more than 13% of children have an anxiety disorder, which includes specific phobia, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and generalized anxiety disorder [15]. A recent large multisite study, the Child/Adolescent Multimodal Study (CAMS), reported the effects of anxiety treatments on a randomly assigned group of 488 children. Children aged 7 to 17 years were given 1 of 4 treatments for 12 weeks: sertraline alone, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) alone, combination sertraline and CBT, or control. The results showed that 81% in the combination group showed significant improvement, 60% of those in the CBT-only group, 55% in the antidepressant group (sertraline), and 24% in the placebo group. This study suggests that first-line treatment for anxiety disorders should include CBT. In addition, this study found that the sertraline group had no more side effects than the placebo group, suggesting safety and tolerability [16].

Obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors are important presentations of childhood anxiety. The large multisite Pediatric Obsessive Compulsive Treatment Study II (POTS) focused specifically on OCD. One hundred and twelve children with OCD, aged 7 to 17 years, entered 1 of 4 study arms: CBT alone, sertraline alone, combination sertraline and CBT, or placebo, over 12 weeks. In this study combination therapy proved to be the superior treatment, followed by CBT or sertraline (neither of which showed superiority to one another). All active treatments were superior to placebo. These results support the use of combination treatment for children with OCD, and identify the lesser impact of CBT or sertraline used alone [17].

It should be noted that these studies looked at CBT and not play therapy, talk therapy, or other therapies. However, many therapists are not trained in this therapeutic method, which highlights 3 common challenges for the pediatrician: identification of patients who might benefit from nonpharmacologic mental health treatment, locating community resources that can apply best-practice mental health treatments (in this case CBT) with children, and circumventing financial barriers that limit access [18].

Depression

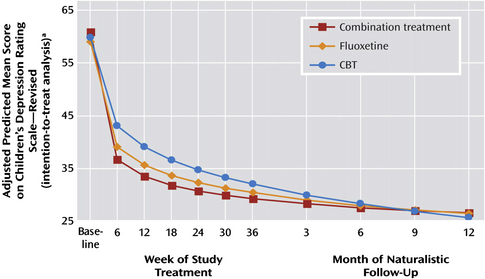

Depression is another common pediatric mental health disorder. Childhood depression can have very serious consequences. In 2005, 16.9% of United States high school students reported seriously considering suicide during the 12 months preceding the survey. More than 8% of students reported that they had actually attempted suicide one or more times during the same period [19]. Many adult physicians treat depression with antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). However, until recently limited pediatric data were available to support an evidence-based approach for the management of depression in children. The Treatment for Adolescent Depression Study (TADS) study examined 327 adolescents with depression in 1 of 4 treatment groups: fluoxetine, CBT, combination of fluoxetine and CBT, or placebo. The results of this important study showed that all 3 treatment groups showed improvement over placebo (Fig. 1). In the first few weeks all 4 groups improved. By 6 weeks post intervention the 3 active treatments were superior to placebo, with the combination treatment group and fluoxetine group showing the greatest changes. Surprisingly, this difference dissipates over time and all 3 treatment groups show significant and equivalent benefits over placebo by 3 to 6 months (see Fig. 1). Therefore, if symptoms require rapid amelioration, such as when depression is severe or associated with significant suicidality, medication should be used in conjunction with CBT [20]. However, in patients with mild to moderate symptoms of depression and taking into account the potential side effects of a medication, CBT is an appropriate first option for families who can access this treatment with an appropriate pediatric CBT provider. Follow-up of the cohort revealed that those children who continued to receive intervention, regardless of the treatment, fared better. This finding would support the idea that ongoing support is helpful in maintaining a positive outcome. The length of this ongoing support is not clear. Interpretation of studies examining antidepressant response in children must be interpreted carefully and replicated, as there is a known high placebo response rate.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Epidemiologic studies revealed prevalence rates for ADHD generally ranging from 4% to 12% in the general population of 6- to 12-year-olds [5,6]. ADHD is characterized by inattention and/or hyperactivity and impulsivity. Many Americans question the very existence of ADHD, and feel that ADHD treatment is unjustified. However, decades of detailed analysis validate the presence, prevalence, morbidity, progression, and scientific validity of this mental health disorder. Until the 1990s there was considerable debate over the management ADHD. In 1995 the Multimodal Treatment Study of children with ADHD (MTA) explored a variety of treatment options. The MTA is the largest study to systematically examine the role of behavioral interventions and/or medication in the treatment of disruptive behavior in children. This study examined 579 children with combined-type ADHD, aged 7.9 to 9.9 years, over a 14-month period. There were 4 treatment arms: treatment with stimulant medication, behavioral intervention, combination of medication and behavioral treatment, and control. The results showed the medicine and medicine plus behavior groups experienced the largest reductions in ADHD symptoms, and the responses were considered superior to those seen by children receiving behavioral treatment alone or in the control group. Furthermore, the behavior plus medication did not show superiority to medication alone in ADHD symptoms [21]. There are limitations to the study, but the overall message is clear. Medication can be an important component of a successful short- to medium-duration intervention for children with ADHD. Behavioral interventions are important tools for the treatment of ADHD symptoms and for children with ADHD and common comorbid conditions. This seminal study led to practice parameters from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) and AAP recommending that medication, specifically stimulants, are an option for the first-line treatment of ADHD in school-aged children [22,23].

Autism

The behaviors associated with autism such as anxiety, hyperkinetic behavior, agitation, and aggression are often severe and debilitating. More than two-thirds of children with autism ultimately try medication to manage these behavior problems [24]. Medication is NOT a treatment for the core symptoms of autism but rather is used to control secondary behaviors that create barriers to progress or danger for patients or others. There are no large or multimodal studies guiding comprehensive medication management for autism. The primary treatment is a multimodal treatment program that incorporates intensive therapy such as applied behavioral analysis, language therapy, occupational therapy, social cognition interventions, and cognitive support [25]. Only when a child fails to respond to interventions or when behaviors are extremely disruptive should medications be considered.

Psychopharmacology

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

SSRIs are a class of compounds typically used in the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders. SSRIs are among the most commonly prescribed antidepressant drugs on the market today. The use of SSRIs in the treatment of behavioral disorders in children is based on the assumption that abnormalities exist in the serotonergic activity of the brain. The primary action of SSRIs is to block the action of the presynaptic serotonin reuptake pump, thereby increasing the level of serotonin in the synaptic gap. Thus the postsynaptic neuron is exposed to more serotonin to treat what is suspected as the cause of many emotional and behavioral disorders [26].

There are 6 SSRIs currently being regularly prescribed in the United States: fluoxetine, sertraline, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, citalopram, and escitalopram. Of the 6, fluoxetine (Prozac) is one of only two SSRIs approved for use by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of children and adolescents aged 8 to 17 years who suffer from depression. It is also approved for the treatment of OCD in children 7 to 17 years of age. Fluoxetine has the longest half-life (between 4 and 7 days) of all the SSRIs. It also takes the longest time to achieve steady state, between 2 and 4 weeks. Its long half-life decreases the symptoms associated with the abrupt discontinuation of therapy, which is a major advantage in regulating treatment and limiting side effects from accidental noncompliance [27]. Fluoxetine tends to be the most activating of the SSRIs. Sertaline (Zoloft) is licensed by the FDA for treatment of children from 12 to 17 years of age who are diagnosed with OCD. Paroxetine (Paxil) is not licensed by the FDA for treatment of children with depression or anxiety. Fluvoxamine (Luvox) is the least activating of all the SSRIs, but interacts with many common medications. It is approved for use in children older than 8 years who are diagnosed with OCD, but has not been approved for treatment of depression in children in the United States. Fluvoxamine has the shortest half-life of all SSRIs, at 15 hours [27]. Because of its pharmokinetics, citalopram (Celexa) is thought to be the SSRI with the fewest drug-to-drug interactions. Escitalopram (Lexapro) is the S-stereoisomer of citalopram. It is typically twice as potent as the racemic version citalopram. Escitalopram is FDA-approved for the treatment of depression in adolescents aged 12 to 17 years [28].

Suicidal ideation

There is ongoing debate about the risk of SSRIs and other antidepressants increasing the chance of suicidal behavior in children and adolescents. Evidence for and against the association of suicidal risk with antidepressant therapy emerged from several randomized trials on adolescents and children [20,29]. In addition, observational studies and population-based studies were reviewed, and the rates of suicide during treatment with antidepressants compared. No clear-cut causal relationship was identified between the use of antidepressants and suicide. This uncertainty led to the creation of an FDA advisory panel to study the issue in more depth. The panel’s meta-analysis determined that there was a small but real increased risk of suicidal thought or behaviors in children and adolescents on SSRIs when compared with placebo. There were no completed suicides in the subjects participating in the studies. The review also found that the time for highest risk of suicidal ideation was in the period of initiation of treatment with antidepressants [30,32]. This finding mirrors the adult treatment experience with SSRIs. It is generally accepted that in the adult population the greatest risk for suicide attempt occurs directly after starting antidepressant therapy. One theory is that the first symptom to improve after initiation of an antidepressant is the patient’s low energy level. This activation may enable a still depressed adult to act on their thoughts. Alternatively, the medication may depress mood or raise anxiety or distress in a minority of treated individuals. The findings of the FDA meta-analysis led the FDA in 2004 to ask the manufacturers of all antidepressant medication to change their labeling to inform patients and families about the issue. The “Black Box” warning states that the use of antidepressants may increase the risk of suicidal ideation and behavior in adolescents and children. In addition, all pharmacies were instructed to provide a patient medication guide along with each prescription. This guide highlights important safety issues and warnings, and is required when families receive any antidepressant [33,34].

Subsequent studies seemed to support that the Black Box warning was necessary [20]. On the other hand, other studies have not supported the need for these warnings. In 2004 the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ACNP) Task Force on SSRI and Suicidal Behavior in Youth included published and unpublished evidence for 15 trials regarding the safety and effectiveness of 5 different SSRI medications (citlopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine). There were no completed suicides and the rate of suicidal behavior was no different between treatment and placebo groups in the studies examined. In addition, the investigators found that only fluoxetine had strong statistical evidence of efficacy [32].

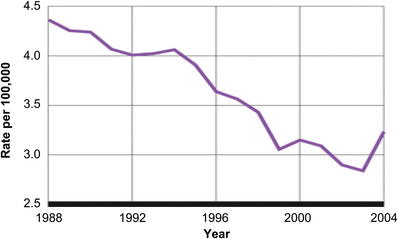

By 2003 there was genuine concern that the Black Box warning may have scared providers, and prescribing rates of these very important medications declined. Olfson and colleagues [34] found that in the decade before the Black Box warning, adolescent suicide rates were declining at rates comparable to the increase in prescribing rates of antidepressant medications. This trend stopped after the Black Box warning was introduced. An increase in suicides and behavior was noted (Fig. 2). New evidence for studies that assessed the effect of the resulting Black Box warning began to emerge. Gibbons and colleagues [35] found that the suicide rates were lower in counties with higher SSRI prescribing rates. These studies have resulted in a shift in opinion about the use of SSRI to treat major depression in adolescents and children. Many clinicians now have accepted a view that the potential benefits of antidepressants outweigh the suicide risk.

Many of the pivotal pediatric studies (TADS, CAMS, POTS) support a consideration of medication in the treatment algorithms for childhood mental health disorders [16,17,20]. These studies all support the combined use of medications along with other modalities. The risk of suicide most often seems to emerge primarily from the depression itself. A decision to not treat a major depressive episode with medication may at times be a bigger risk than the risk of using SSRIs. Clinicians must consider the severity of illness, the availability of nonmedication therapies, and the literature on antidepressants and suicide risk when choosing a path for treatment of their individual patients.

Monitoring

The FDA Black Box warning led to an additional recommendation for a follow-up schedule to monitor children started on SSRI medications. This procedure was extremely restrictive, suggesting weekly visits for 4 weeks, then every other week for 4 weeks, and so forth. These recommendations were found to be unrealistic and were not followed by practicing providers for obvious reasons. The new recommendations for monitoring children and adolescents started on SSRI state that they “…should be monitored and observed carefully by mental health providers and family members” [36,37]. Monitoring should include the watching for a worsening of depression or the onset of suicidal ideation. Also important in the initiation phase of intervention is the need to pay attention to potential side effects of SSRIs. This change in monitoring recommendation allows practitioners to develop an individualized approach that includes in-person visits combined with telephone follow-up monitor a patient’s response to medication. There is no recommendation to check laboratory tests or electrocardiogram (ECG) when using SSRIs.

Other adverse effects

SSRIs are generally well tolerated. The recognized side effects of SSRI include headache, abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, sleep changes, jitteriness or agitation, diaphoresis, and change in sexual function. As with all antidepressants there is the possibility of an induced manic or hypomanic episode, particularly in individuals with a predisposition to bipolar disorder. Anecdotally, some children and adolescents are very sensitive to even low doses of SSRIs. Common behavioral side effects of even low-dose SSRIs include agitation, an escalation in anxiety, and an increase in impulsiveness or disinhibition [38]. The possibility of these negative side effects makes it imperative to monitor carefully, especially in vulnerable populations such as those with autism, traumatic brain injury, or cognitive deficiency.

Serotonin syndrome

The use of SSRIs is also associated with a small risk of serotonin syndrome. Sometimes the cause is idiopathic or metabolic in nature, but also may be the result of drug-to-drug interaction or overdose [39]. Serotonin syndrome is the consequence of flooding the central nervous system with serotonin. The symptoms emerge suddenly and may include a change in mental status: anxiety, agitated delirium, restlessness, or disorientation. Physical manifestations can include autonomic effects such as diaphoresis, tachycardia, hyperthermia, hypertension, vomiting, and diarrhea, and neuromuscular hyperactivity such as tremor, muscle rigidity, myoclonus, and hyperreflexia [40]. Serotonin syndrome can be life threatening.

Dosage

The recommended dosage ranges that are currently published in the literature are controversial, and may reflect more the historical ranges that are recommended for adults. Primary care pediatric providers are best served by a much more conservative approach. Adjusting the adult dosage in the table downward to between one-half to one-third of the adult dosage is a common approach [38]. For example, fluoxetine might start at 4 mg in a preadolescent. Although it may sound like an oversimplification, many practitioners ascribe to the “common lore” of “start low and go slow.”

“SSRI addiction”

The abrupt termination of SSRI usage by patients has been recognized as a major issue. This withdrawal syndrome has lent credence to the idea that SSRIs are addictive. There is no evidence to support this idea, but abrupt cessation of these medications can trigger a cascade of uncomfortable symptoms, which can be avoided if the medications are tapered over a period of weeks. The symptoms of serotonin withdrawal syndrome are disequilibrium, nausea and vomiting, fatigue and lethargy, myalgia, tremor, insomnia, migraine-like auras, agitation, anxiety, crying spells, irritability, low mood, and vivid dreams. Some medications have a much higher likelihood of causing this problem. The medications with shorter half-lives have a significantly higher chance of causing withdrawal symptoms. Fluoxetine is the least likely to cause severe symptoms of withdrawal, and paroxetine or fluvoxamine the most likely to cause discontinuation symptoms [41]. Some consideration could be given to switching from a short-acting SSRI to fluoxetine as a tool for tapering, with a reduced chance of causing distress.