Surgical Treatment of Lower-Genital-Tract Infections

The management of most bacterial and viral lower-genital infections in pregnancy is generally accomplished by medical treatment. Many of these infections are caused by sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Their management is beyond the scope of this chapter; management is reviewed in the treatment guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1998). There is little role for the surgical management of acute bacterial or viral infections, except the surgical drainage of vulvovaginal abscesses. The role of surgery in chronic bacterial or viral infections is also limited and is best deferred until completion of pregnancy unless significant symptoms dictate earlier intervention.

The clinical presentation of vulvovaginal surgical infections is probably affected minimally by pregnancy. However, it may be altered by host factors that should be evaluated prior to decisions regarding medical or surgical treatment. These include, but are not limited to, diabetes mellitus, cancer, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and treatment with immunosuppressive drugs. Immunosuppression from human immunodeficiency viral infection and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) may mask clinical and laboratory signs of local infection and bacteremia due to granulocytopenia and impaired inflammatory response (Berger and associates, 1994). It may also affect the clinical response of chosen therapy, although little is known about this relationship (Harris, 1997; Lord, 1997).

VULVAR ABSCESS

Vulvar or vestibular abscesses occasionally complicate pregnancy. Acute infections may follow pyogenic bacterial folliculitis. Chronic or recurrent vulvar abscesses may occur in women with furunculosis, carbuncles, or hidradenitis suppurativa. Often, small abscesses may be quite debilitating and painful. Most superficial infections become fluctuant and will spontaneously drain. Hot baths or packs may accelerate the temporal course of deeper abscesses to pointing.

It is sometimes difficult to differentiate cellulitis from an abscess; however, needle aspiration of the infected area will generally elucidate the correct diagnosis. Pathogenic bacteria are usually normal skin flora, but mixed aerobic and anaerobic infections are common. In immunocompetent patients, Gram stain and bacterial culture add little to the clinical management; however, in complicated infections laboratory identification of the dermatopathogen may be helpful.

Small, superficial vulvar abscesses are best treated by simple incision and drainage. Such minor abscesses may be incised with a No. 11 scalpel blade with a vertical incision following the natural Langer cleavage lines. Most cases can be performed under local anesthesia and managed as outpatients. Small cavities do not require gauze packing, but local hydrotherapy may assist healing. Many clinicians add broad-spectrum oral antimicrobial treatment after drainage, but this is of uncertain benefit.

Hospitalization for surgical drainage should be considered if there is immunocompromise, or if significant surrounding cellulitis is present. Overwhelming septicemia and necrotizing fasciitis have been described, complicating surgical treatment in these settings (Cruikshank and McLauchlan, 1987). If the abscess is suspected to be multilocular or deep, surgical exploration may be easier under general anesthesia or spinal analgesia. Broad-spectrum antimicrobials, such as cefoxitin or ampicillin with sulbactam, are often administered prior to surgery to cover transient bacteremia and treat cellulitis.

There are very few indications during pregnancy for definitive surgical therapy for chronic hidradenitis suppurativa (Fig. 14-1). This chronic multifocal vulvar apocrine gland infection during pregnancy may cause recurrent abscesses or a malodorous vulvar exudate. Antepartum isotretinoin and antiandrogen therapy is contraindicated, but prolonged broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy may improve symptoms. More extensive surgical therapy, such as “unroofing” infected pockets and tunnels, or wide local excision of involved areas, is best postponed until after pregnancy.

FIGURE 14-1. Hidradenitis suppurativa showing multiple chronically infected, communicating draining sinus tracts.

BARTHOLIN GLAND ABSCESS

Little is known about the epidemiology of Bartholin gland infection and its complications in adult or pregnant women. In nonpregnant women, it is most commonly associated with age 20–29 years, nulliparity, and lower socioeconomic status. It is not related to ethnicity or marital status (Aghajanian and colleagues, 1994). These women often have prior or concomitant STDs, particularly gonorrhea and chlamydial infection. The demographic characteristics have led to the conclusion that acute Bartholin gland infection is probably an STD. However, recurrent infections or abscesses may be the consequence of scarring of the gland duct damaged by a prior infection.

MICROBIOLOGY

The microbiology of Bartholin gland infection is similar to that of pelvic inflammatory disease (Brook, 1989; Lee and associates, 1977). Most abscesses have mixed aerobic and anaerobic pathogens, some will be single-pathogen infections, and in up to one-third no pathogen is isolated by culture. The predominant organisms are those of the normal vaginal flora, including gram-negative anaerobic rods, gram-positive anaerobic rods, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus. Many investigators have isolated Neisseria gonorrhoeae and, to some extent, Chlamydia trachomatis from abscesses (Brook, 1989; Saul and Grossman, 1988). Interestingly, Sing and colleagues (1998) presented a case of bartholinitis secondary to Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum do not appear to be important pathogens in most Bartholin gland abscesses (Lee and colleagues, 1977). While most Bartholin gland cysts are sterile, and most abscesses contain bacteria, there is a spectrum of their clinical presentation and microbiology.

Clinical presentation of a Bartholin gland infection is usually at the abscess stage. Ductal infection alone is unusual. Abscesses are generally unilocular and several centimeters in diameter. Surrounding erythema, induration, and tenderness may obscure actual abscess size. A careful examination for signs of necrotizing fasciitis should precede decisions on the optimal treatment, especially in immunocom-promised women, including those with diabetes. Indeed, acute bartholinitis can cause diabetic ketoacidosis. Septic shock and a toxic shock-like syndrome can also complicate Bartholin gland infections (Carson, 1980; Lopez-Zeno, 1990; Shearin, 1989; and their colleagues).

Decisions concerning appropriate therapy depend on underlying immune status and severity of infection. In general, immunocompetent women with early, mild infection or a small abscess can be treated with a broad-spectrum oral antimicrobial agent, analgesics, and local heat by packs or Sitz baths. Spontaneous drainage often occurs within 2–3 days during such local therapy. Alternatively, if the abscess is larger and fluctuant, then surgical drainage may be technically easier.

SURGICAL THERAPY

Several surgical techniques have been proposed for management of Bartholin gland abscesses. These include incision and drainage, marsupialization, and catheter drainage. None of these has undergone randomized, prospective evaluation in sufficiently large trials to exclude differences in outcome.

There are four main goals of surgical treatment for Bartholin gland abscesses. First, there must be adequate surgical drainage of the infected gland and abscess. Second, the gland should be preserved, so that it may continue its secretory function. Third, recurrences should be prevented by creation of a new gland ostium or fistula to replace the function of the presumed damaged or occluded duct. Fourth, complications of the infection such as necrotizing fasciitis and sepsis should be prevented.

There is little indication in abscess management for primary excision of the Bartholin gland. Excision may be associated with intraoperative hemorrhage, postoperative hematoma, and subsequent dyspareunia from vulvar scarring and lack of Bartholin gland lubrication (Zuspan and Quilligan, 1988). The purpose of other surgical techniques is to establish immediate drainage and subsequent development of a new gland ostium. The new opening is actually a cutaneous fistula that may take several weeks to fully epithelialize. Patency of this tract allows continued gland secretion without cyst or recurrent abscess formation.

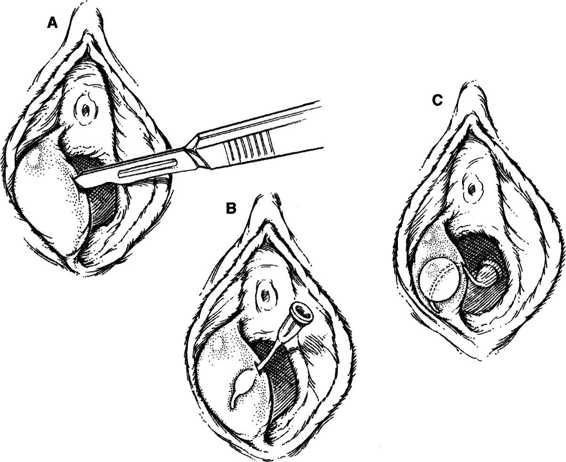

TECHNIQUES. The simplest technique is incision and drainage that involves creating a 1-cm vertical stab wound with a No. 11 or 15 scalpel blade into the abscess cavity (Fig. 14-2). If the abscess has drained spontaneously, then the opening may be extended further. The cavity is explored with a tissue forceps, evacuated, and irrigated. A self-retaining Word catheter (10-French, 5-cm length, 5-mL balloon tip) is inserted into the cavity, and the proximal bulb is inflated with 2–5 mL of water (Word, 1964). The bulb should be inflated sufficiently to prevent spontaneous catheter expulsion through the gland opening, as well as to avoid painful dilatation of the gland. Local hydrotherapy or Sitz baths may aid healing, but discomfort from the catheter is common unless the distal end is cephalad from the introitus. The Word catheter may be removed after there has been sufficient epithelialization of the new fistula, usually 1–4 weeks. The recurrence rate with this technique is approximately 10 percent (Heath, 1988).

FIGURE 14-2. Management of a Bartholin gland abscess using the Word catheter. A. A stab wound is made into the abscess using a No. 15 scalpel blade. B. Insertion of catheter in cavity. C. Properly inflated balloon tip with external catheter tip directed into vagina.

Marsupialization of the Bartholin gland abscess also can be safely accomplished after drainage (Fig. 14-3). The procedure may require general or regional anesthesia, but usually can be accomplished with local infiltration or pudendal block. The technique has been variously described using fine absorbable suture to exteriorize and reapproximate the

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree