Fig. 16.1

Anatomy of pudendal nerve

This test employs a disposable electrode that is placed around the gloved fingertip and inserted into the rectum (Fig. 16.2). Transrectal stimulation of the pudendal nerve is performed while measuring the time from electrical stimulus of the pudendal nerve to the onset of the electrical response in the muscles of the pelvic floor (Fig. 16.3). Prolonged PNTML indicates pudendal neuropathy. Unfortunately normal latencies do not exclude nerve injury as only the fastest remaining conducting fibers are recorded [34]. In addition, there can be anatomic overlap of the pudendal innervation on both sides of the external anal sphincter [35].

Fig. 16.2

Probe used for pudendal nerve terminal motor latency test (Source: http://www.glowm.com/section_view/heading/Neurophysiologic%20Testing%20of%20the%20Pelvic%20Floor/item/57. Used with permission)

Fig. 16.3

Schematic representation of the system for measuring the pudendal nerve terminal motor latency (PNTML). Latency of the evoked muscle action responses in external anal sphincter (EAS) muscles is recorded after stimulation of both right-sided and left-sided pudendal nerve at the point of ischial spines. A. Stimulating anode. B. Stimulating cathode. C. Ground electrode. D. Recording electrodes (Used with permission from Tomita R, Igarashi S, Ikeda T, Koshinaga T, Fujisaki S, Tanjoh K. Pudendal Nerve Terminal Motor Latency in Patients with or without Soiling 5 years or more after Low Anterior Resection for Lower Rectal Cancer. World Journal of Surgery. 2007; 31(2): 403–408)

Endorectal Ultrasound

In women with suspected obstetrical injury or patients who have a history of anorectal procedures, endorectal ultrasound is a simple test for defining defects in the internal and external anal sphincter muscles. The most frequently used instruments have a 360° rotating transducer and work with 7 or 10 MHz. More recently three dimensional probes have become popular. Both sphincters can be visualized and length and width can be determined. Atrophy, scar tissue, and defects in the sphincters can also be seen [18] (Fig. 16.4). This technique, similar to ultrasound in other areas of the body, is operator dependent and requires training and experience. However, when performed by an experienced clinician, this test approaches 100 % sensitivity and specificity in identifying sphincter defects [36–38].

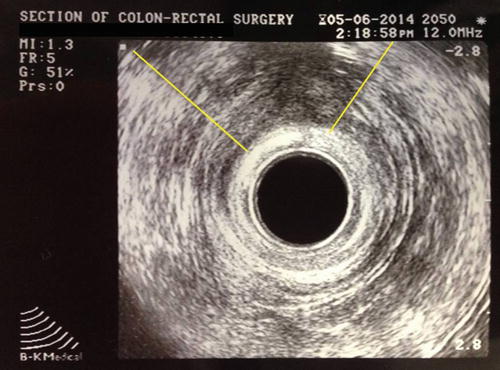

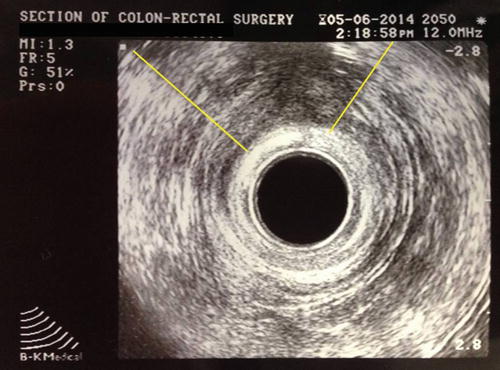

Fig. 16.4

Endorectal ultrasound demonstrating an external sphincter defect

Defecography

Defecography can be performed under fluoroscopy or using Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). Both techniques involve filling the rectum with either a barium paste in the case of fluoroscopic imaging or ultrasound gel in the case of MRI. Static images at rest and during squeezing and pushing allow measurement of the anorectal angle (Fig. 16.5a, b), perineal descent, and anal canal length. It has been demonstrated that the anorectal angle is increased in pelvic floor denervation as a sign of pelvic floor weakness. However there is wide interobserver variation in the measurement of the anorectal angle which perhaps makes quantification of limited clinical value [18]. Rectal intussusception, full thickness prolapse, rectoceles, and enteroceles can also be observed. Fluoroscopic defecography tends to be a better test in some cases since the patients are sitting up in the actual position in which one normally defecates, whereas during MR defecography the patient is laying supine and it is often difficult to evacuate the gel in this non-physiologic position. In addition, although both tests can detect a number of abnormalities, these abnormalities can also be seen in otherwise asymptomatic individuals and their presence often correlates poorly with impaired evacuation [39, 40].

Fig. 16.5

(a, b) Normal anorectal angle at rest (a) and with straining (b)

Treatment

Medical

After a complete history and physical examination with the addition of necessary physiologic tests, supportive measures are frequently the first approach. It is recommended for patients to keep a bowel and food diary to try and identify offending agents. For patients with diarrheal stool, one would have patients cut lactose and dairy out of the diet to evaluate for possible triggers. Trying to promote a regular ritualized bowel habit is also important. Often times, patients will not empty their rectum completely and residual stool in the rectum may seep or leak out. In these cases, bowel management programs and a regular enema may be useful to promote more complete evacuation. This type of regimen is especially helpful in patients with spinal cord injuries. In patients with loose or segmented stools, a fiber supplement is often recommended. Fiber helps to bulk the stool and promote complete emptying all at once as opposed to having to go back and forth to the bathroom several times. Unfortunately, fiber supplements can potentially worsen diarrhea by increasing colonic fermentation.

For patients with liquid or even mushy stools, Loperamide (Imodium®—McNeil Consumer & Specialty Pharmaceuticals, Fort Washington, PA) and diphenoxylate/atropine (Lomotil®—Pfizer, New York, NY) can produce modest improvement in symptoms related to fecal incontinence. A placebo controlled study of loperamide 4 mg TID has been shown to reduce the frequency of incontinence, improve stool urgency, increase colonic transit time, reduce stool weight, and interestingly, increase anal resting sphincter pressure [41–43]. Other medications that can be used are Codeine sulfate, which can cause drowsiness and addiction, or Cholestyramine (Questran®—Par Pharmaceuticals Inc., Spring Valley, NJ), which is a bile acid binding agent (Table 16.1).

Table 16.1

Classification of antidiarrheal medications

Category | Mechanism of action | Medication |

|---|---|---|

Adsorbents | ||

Fiber supplements | Adsorb water Reduce fecal water content Increase consistency of stool | Psyllium husk (Metamucil®) Methylcellulose (Citrucel®) Guar gum Calcium polycarbophil (FiberCon®) Wheat dextrin (Benefiber®) |

Bile acid sequestrant | Forms insoluble complexes with bile acid Makes bile acids osmotically inactive | Cholestyramine (Questran®) |

Antispasmodics | Decreases motility Slows passage of stool Allows more time for salt and water to be absorbed | Opiods (Codeine sulfate) Diphenoxylate/atropine (Lomotil®) Diphenoxin/atropine (Motofen®) Loperamide (Imodium®) |

Inhibits hormonal secretion Decreases motility Decreases secretion | Octreotide acetate (Sandostatin®) | |

Anti-inflammatory | Stops expulsion of fluid into the bowel lumen by coating the mucosa Reduces inflammation/irritation of the intestinal mucosa Antibacterial | Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol® and Kaopectate®) |

Biofeedback

Behavioral therapy using “operant conditioning” techniques has been shown to improve bowel function and incontinence [44]. The main principle is that patients acquire new and better behaviors through a process of trial and error. The goals of biofeedback are to improve the strength of the anal sphincter muscles, improve the coordination between the abdominal, gluteal, and anal sphincter muscles, and enhance the anorectal sensory perception [1]. The benefit is variable, but improvement in as much as 64–89 % of patients has been reported [45, 46]. Careful selection of patients is crucial and includes factors such as motivation, ability to understand instruction, some rectal sensation preservation, and ability to contract the external anal sphincter voluntarily [47].

Anal Plugs

The anal plug enables controlled evacuation and helps reduce skin complications by temporarily occluding the anal canal. The plug is attached to the perineum using tape and can easily be retrieved. It is effective in controlling incontinence in a minority of patients who can tolerate its use [14] (Fig. 16.6).

Fig. 16.6

Anal plug (Courtesy of Coloplast, Minneapolis, MN)

Surgical Modalities

Surgery should be considered in selected highly symptomatic patients who have failed conservative measures.

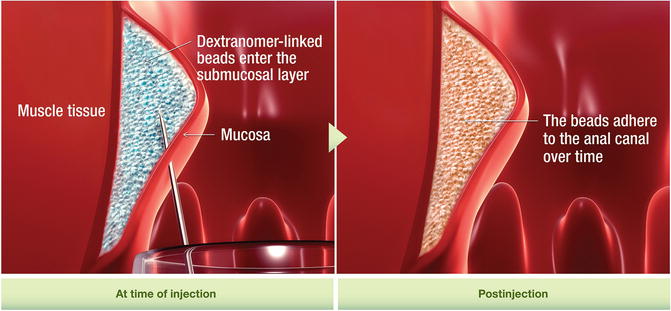

Anal Encirclement Procedures

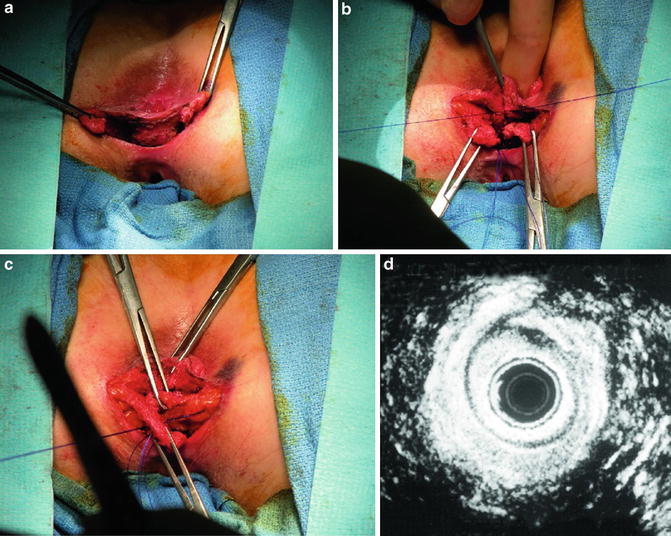

Anal encirclement was originally described by Thiersch in 1891 for the treatment of complete rectal prolapse. This was later adopted for the treatment of fecal incontinence. A variety of materials have been used for this procedure including nylon, silk, strips of fascia, silver wire, silastic bands, and bioabsorbable materials [18, 48] (Fig. 16.7a–d). The goal of the procedure is to create a rigid barrier to the passage of stool. In general, the perioperative morbidity rate is high with a variety of complications described including fecal impaction, infection, breakage of the encircled material, or erosion through the skin [14, 49]. This procedure has largely been abandoned because of poor results and high postoperative complication rate.

Fig. 16.7

(a–d) Anal encirclement (Thiersch) procedure

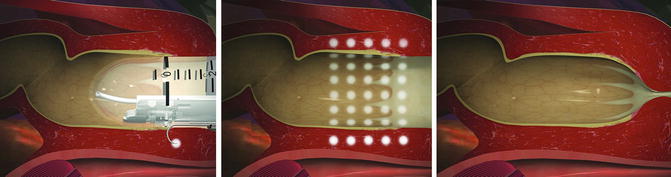

Radiofrequency

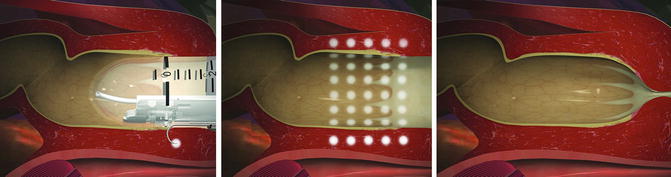

Radiofrequency energy or the Secca® procedure (Curon Medical Inc., Sunnyvale, CA) uses heat generated by a high-frequency alternating current that flows from four electrodes causing frictional movements of ions and tissue heating. This procedure is done under sedation and local anesthetic. The device is placed under direct vision into the anal canal and needles are deployed into the tissue and into the sphincter muscles (Figs. 16.8a, b and 16.9). The generator then delivers energy (465 kHz, 2–5 W) at each needle electrode for 90 s or until the temperature reaches 85 °C. The mucosa is constantly cooled by chilled water at the base of each needle. There is constant temperature monitoring and feedback to control the amount of energy delivered to tissue. The therapeutic goal is to create thermal lesions or a controlled scar in the muscle while preserving mucosal integrity. There are variable results in the literature. In a study by Ruiz et al., of 24 patients who underwent the procedure, 16 were available for follow-up. The mean treatment time was 46 min and the number of radiofrequency lesions in the anal canal varied from 31 to 80. Four patients (25 %) experienced minor complications including bleeding, diarrhea, and constipation. Four patients (25 %) had worsening of their incontinence and 2 patients (12.5 %) had no improvement. Overall, 10 of 16 patients (62.5 %) had improvement but still had moderate incontinence at 1 year follow-up [50]. The exact mechanism of this procedure is not known. No consistent changes in anal manometry or anorectal ultrasound have been reported [51–53]. More studies are needed to determine which patients would benefit from this minimally invasive treatment.

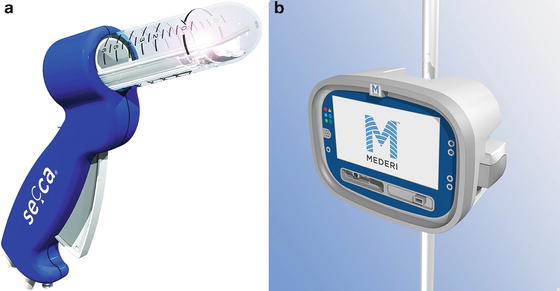

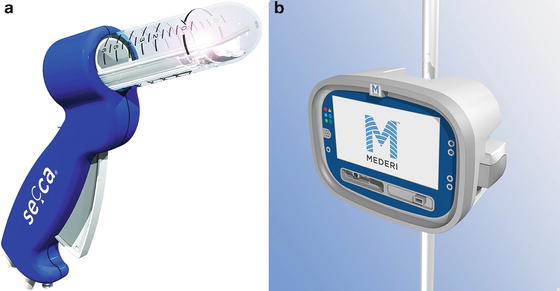

Fig. 16.8

(a, b) Secca® Radiofrequency device (Courtesy of Mederi Therapeutics, Norwalk, CT; ©2014 Mederi Therapeutics, Inc.)

Fig. 16.9

Secca® procedure (Courtesy of Mederi Therapeutics, Norwalk, CT; ©2014 Mederi Therapeutics, Inc.)

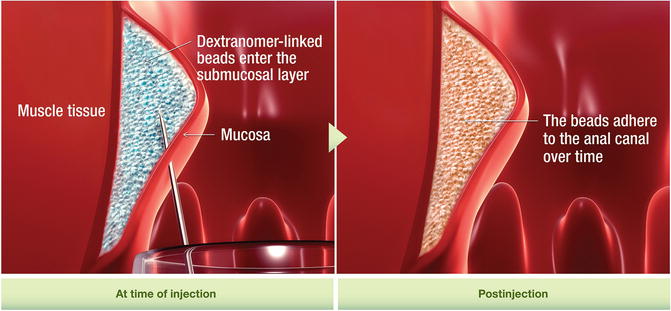

Bulking Agents

Injection of bulking agents has emerged as a new treatment for fecal incontinence following success that has been reported in treating urinary incontinence. Many different injectable materials have been used including autologous fat, Teflon, bovine glutaraldehyde cross-linked collagen, carbon-coated zirconium beads (Durasphere®), polydimethylsiloxane elastomer, dextronamer in nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA™ Dx), hydrogel cross-linked with polyacrylamide (Bulkamid), porcine dermal collagen (Permacol), silicone biomateraial (PTQ™), synthetic calcium hydroxylapatite ceramic microspheres, and polyacrylonitrile in cylinder form. These materials can be injected in different ways including through the perianal skin into the intersphincteric space or through the anal mucosa into the submucosa. Injection can be guided digitally or can be done under ultrasound guidance [54].

The goal of injection is to bulk up the tissue inside the anal canal in order to approximate the anal mucosa. In doing so, this should close the anal canal or raise the pressure inside the anal canal to prevent leakage of stool. Studies looking at the results of this treatment are limited. There is lack of information regarding the volume of injection, ideal site of injection, and the route it should be injected. One large randomized trial comparing NASHA™ Dx to sham injections demonstrated that NASHA™ Dx is efficacious in the treatment of fecal incontinence with a follow-up of 12 months [55]. There are no studies looking at long-term benefit. In a review of all the studies published to date, the injection of bulking agents appears relatively safe; however, minor adverse events are relatively common (discomfort, pain, bleeding, abscess, and leakage of injected material) [54, 55] (Fig. 16.10).

Fig. 16.10

Solesta® injection (Courtesy of Salix Pharmaceuticals, Raleigh, NC)

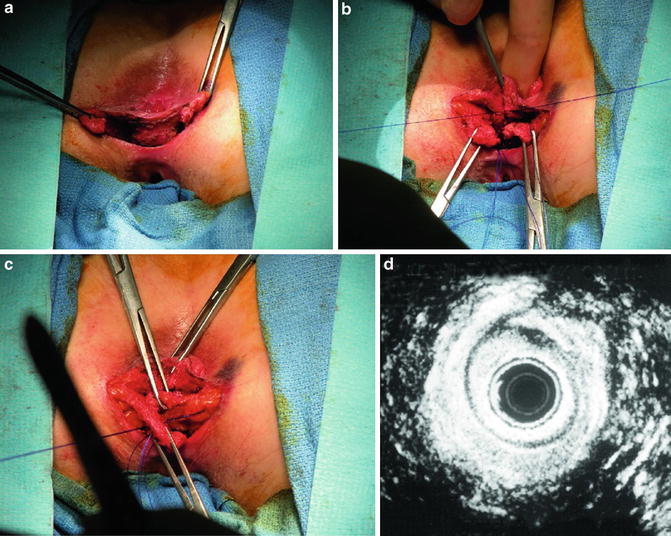

Overlapping Sphincteroplasty

Overlapping sphincteroplasty is offered to highly symptomatic patients with an anterior external anal sphincter defect secondary to an obstetric or iatrogenic trauma. The procedure typically involves a full mechanical bowel preparation and pre-procedure intravenous antibiotics. A transverse incision is made over the perineum. Dissection is carried up to the level of anorectal ring and the anal mucosa is separated from the sphincter complex. Care is taken not to carry the dissection too far laterally as the nerve supply to the external anal sphincter enters posterolaterally. The fibrous remnant of the external anal sphincter is then divided. End-to-end repair has been described but retraction of the ends of the muscle and lack of a bulking effect because of excision of the scar tissue has been implicated in the suboptimal results [56].

For overlapping repair, the scar at the ends of the sphincter is preserved to aid in anchoring the sutures. The ends of the mobilized external sphincter are overlapped and sutured together with absorbable mattress sutures. Plication of the internal anal sphincter may be concurrently performed. Anterior levatoroplasty and closure of the perineal incision in a V–Y manner can help to bulk up the perineal body and increase the anovaginal distance. Typically, the wound is left partially open to promote drainage [18] (Fig. 16.11a–d). Satisfactory results, which are defined as continence for solid and liquid stools, have been reported in 70–100 % of patients [7]. However, the majority of patients will not have perfect continence, and many patients will have residual symptoms. Some patients may even develop new evacuation problems [57]. The most important factor in the return of normal sphincter function seems to be an increase in squeeze pressures [58]. Poor outcome is usually associated with pelvic floor denervation or a residual sphincter defect [59, 60].

Fig. 16.11

(a–d) Overlapping sphincteroplasty (Used with permission from Seo CJ, Wexner SD, Davila GW. Reoperative Surgery for Anal Incontinence. In Billingham RP, Kobashi KC, Peters WA. Reoperative Pelvic Surgery. New York: Springer Science + Business Media: 2009)

In a study looking at functional results of sphincter repair after a median of 10 years, zero patients were fully continent to flatus or stool [61]. Reasons for failure or decline of continence can be explained by weakening of the muscle because of normal aging, repair breakdown, or a combination of these factors [62]. Repeat sphincter repair can be performed in patients with recurrent symptoms, especially if breakdown of the repair is verified on endoanal ultrasound. It has been demonstrated that the long-term results of a repeat sphincter repair are approximately equivalent to those for primary overlapping sphincter repair [63].

Postanal Repair

Postanal repair was first described by Sir Alan G. Parks in 1975 [64]. This technique was described specifically for idiopathic or neurogenic incontinence and for incontinence following surgery for the repair of rectal prolapse. These conditions are associated with lengthening of the anorectal angle and shortening of the anal canal as a consequence of sphincter denervation [7]. The procedure is also advocated for patients with “weak” sphincters but no anatomic sphincter defect [14].

The procedure is performed through a curved incision posterior to the anus with dissection through the intersphincteric space, through Waldeyer’s fascia and into the pelvis. The ileococcygeus, pubococcygeus, and puborectalis muscles are plicated using a series of polypropylene sutures. Further plicating sutures can be placed in the deep and superficial parts of the external anal sphincter muscle using polyglactin suture [18]. The goals of the procedure are to restore the anorectal angle and to tighten the anal sphincter muscle. Although, Parks reports successful outcome in approximately 80 % of patients, these results have not been reproduced [7]. The mechanism of restoration of continence is unclear as the anorectal angle does not change significantly following this procedure and the manometric evaluation of sphincter function is variable [65, 66]. Improvement after this procedure may be caused by creation of a local stenosis or a placebo effect rather than improvement of muscle function [18].

Muscle Transposition

The most common skeletal muscle used in transposition techniques is the gracilis. Gracilis muscle transposition was first described by Pickrell in 1952 [67]. The muscle is freed from its insertion, completely mobilized, and subcutaneously tunneled to the perineum. It is then wrapped around the anus and anchored with sutures to the contralateral ischial tuberosity or the inferior ramus of the pubic bone. The gracilis muscle is mostly composed of type two muscle fibers that are short acting and fast twitch fibers. Therefore, the muscle is fatigable and only contracts by will. Dynamic graciloplasty combines gracilis muscle transposition with an implantable electrical stimulator. This applies chronic low-frequency stimulation which functions to change the composition of the muscle to long acting, slow twitch, non-fatigable, type one muscle fibers. The procedure has a variable success rate with reports as high as 72 %. Given the steep learning curve of this technique, there is a high complication rate. Most complications are minor, but infection and rectal perforation are described [68]. Unfortunately this has not been approved for use in the United States. Other muscles that have been transposed include the gluteus maximus muscle [69], pubococcygeus [70], transverse perineal muscle [71], and even the antropylorus [72]. Free muscle transplantation has also been described [73].

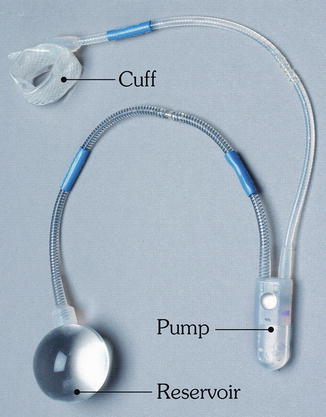

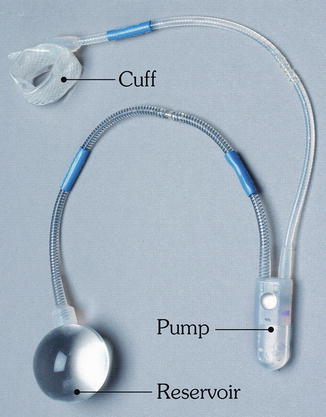

Artificial Bowel Sphincter

The artificial bowel sphincter (ABS) was adapted from the artificial urinary sphincter which was introduced in 1972 by American Medical Systems (AMS). In 1987, the first description of the use of the artificial urinary sphincter was reported for fecal incontinence. The patient had an excellent result with no complications at a follow-up of 3 months [74].

Since then, modifications have been made to the artificial urinary sphincter to make it more applicable for use around the anus which culminated in the development of the Acticon Neosphincter™ (AMS, Minnetonka, Minnesota). The procedure involves encirclement of the anus with an implantable fluid-filled, silicone, elastomer cuff that is connected by tubes to a control pump and a pressure-regulating balloon. Cuff lengths range from 7 to 14 cm with three cuff widths of 2, 2.9, and 2.4 cm. The control pump is implanted in the labia or the scrotum and the balloon is implanted in the space of Retzius. The inflated cuff compresses the anus all the time. When the patient has to defecate, the fluid is manually pumped from the cuff to the balloon by using the control pump. The empty cuff allows the passage of stool and then the pressure in the balloon sends the fluid back into the cuff (Figs. 16.12 and 16.13).

Fig. 16.12

The Acticon® artificial bowel sphincter device (American Medical Systems) (Used with permission from Goh M, Dioknow AC. Surgery for Stress Urinary Incontinence: Open Approaches. In Badlani GH, Davila GW, Michel MC, de la Rosette JJMCH, eds: Continence. London: Springer Science + Business Media, 2009)

Fig. 16.13

Illustration of the implantation of the artificial bowel sphincter

In a multicenter, prospective, nonrandomized clinical trial looking at 115 patients, 6 patients were aborted because of perforation. Device-related complications were reported in 86 % of enrolled patients. Forty six percent of patients required device revisions to treat major adverse events including infection or erosion and 36 % required explantation. At the end of the follow-up period of 1 year, 75 of 112 patients (67 %) had functioning devices [75].

The magnetic anal sphincter (MAS) (FENIX™; Torax Medical Inc., Shoreview, MN) is a novel artificial sphincter mechanism which was recently described. This was originally used in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. This device is composed of a series of titanium beads with magnetic cores inside. The beads are interlinked with titanium wires to form a flexible ring that is implanted around the external sphincter in a circular fashion (Fig. 16.14). The device is manufactured in different lengths based on the number of beads (14–20) [76].