Surgical Instruments and Drains

Surgical instruments are expensive, and, unfortunately, their quality and design varies significantly among the various suppliers. Instrument manufacturing is still somewhat of a “cottage industry.” A commercial surgical instrument company may dictate the design of an instrument and the materials to be used in manufacturing the instrument; and when these criteria are met, and the cost is competitive, an order will be placed for a quantity of instruments which will then be stamped with the retailer’s name and catalogue number. The retailer may get different instruments from different manufacturers, and the retailer’s sources may change from time to time. This allows subtle but definite differences to occur, even in the same instrument series ordered from the same retailer. It is tempting for the hospital’s procurement personnel to purchase a similar but cheaper instrument when there is a “budget crunch.” In the case of surgical instruments, this should not be done without the knowledge and approval of the physicians and the operating room personnel who will use the instruments.

Also, it is essential that the quality of surgical instruments be the same in the hospital’s labor and delivery suite as it is in the hospital’s main operating rooms. In many hospitals, all of the surgical instruments are returned to a central service for cleaning, sterilization, and repackaging. It is frustrating to a surgeon to have to work with instruments that might not vary in appearance, but which definitely vary in quality. The good example is that of hysterectomy clamps (eg, Heaney-Ballentine clamps). They should be bought and kept as sets. If this is not done, clamps bought at different times or from different retailers may have jaws of slightly different lengths or slightly different curves. When this is the case, they do not fit as well side-by-side when excising the uterus from adnexal structures. The worst case scenario occurs when a single-use instrument, such as a disposable scissors or hemostat, is returned to central service where it may be sterilized and ultimately be placed in a surgical case tray. These instruments should be discarded, and those who sterilize the instrument sets must be notified that the set is at that point incomplete.

It is best to have a knowledgeable and interested surgeon work with labor and delivery and operating room personnel to select the instruments that are to be purchased and to establish the contents of a basic instrument set for vaginal deliveries, abdominal deliveries, dilatation and curettage, cervical cerclage, peripartum hysterectomy, and so on. There will always be a need for a few extra instruments (eg, scissors, needle holders, thumb forceps, etc) to be sterilized and wrapped separately to replace an instrument that may be contaminated or found to be defective. It is usually best to discard a defective surgical instrument rather than to repair it. It is possible to sharpen surgical scissors, but, in time, sharpening affects the alignment of the blades and prevents the scissors from making a clean cut of tissue and suture material.

LIGHTING DEVICES

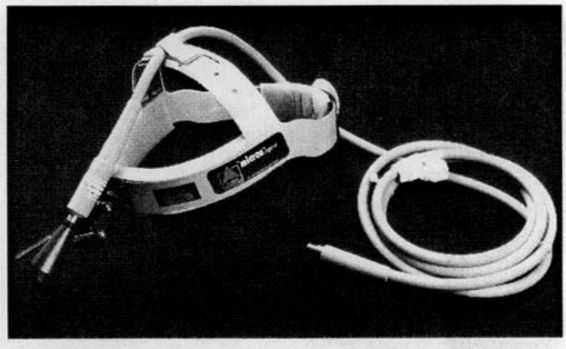

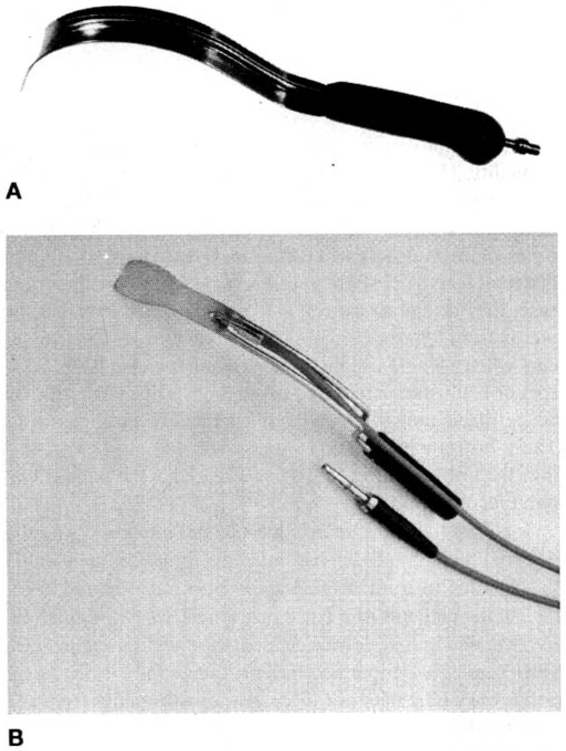

Although operating room lighting is usually adequate for routine surgical procedures, this is not always the case in delivery rooms. If additional lighting is required for deep spaces, a fiberoptic head light can be invaluable, in both the delivery room and the operating room (Fig. 2-1). In addition for abdominal and vaginal work, one might consider using a lighted retractor (Fig. 2-2) or a suction-illumination-irrigation system (Fig. 2-3).

FIGURE 2-1. Surgical headlamp.

FIGURE 2-2. Illuminated retractors. A. Lighted Deaver retractor. B. Miyazaki All-Purpose retractor (Photo courtesy of Marina Medical).

FIGURE 2-3. Disposable irrigation, suction, illumination system. VITAL VUE Suction w/Bulb Tip. (Modified and reprinted with the permission of United States Surgical, 1999.)

INSTRUMENTS FOR SUTURING

Commonly used needle holders have either serrated or longitudinal teeth and are manufactured in both straight and curved (Heaney) configurations (Figs. 2-4 and 2-5). The Heaney needle holder is especially useful in placing needles in deep abdominal recesses and in performing vaginal surgery. The rings in the handles of needle holders assist the novice surgeon in manipulating the instrument. With time and experience, the surgeon acquires the ability to “palm” the instrument, that is, place and manipulate needles as well as lock and unlock the needle holder without placing the fingers of the dominant hand through the rings (Figs. 2-6 and 2-7). Using this technique, the surgeon can quickly run suture lines in tissues such as myometrium or fascia without the need to remove the fingers from the needle holder or reposition the needle manually after each stitch. The surgeon should strive to perfect this technique for use of needle holders, and extend it when possible to all instruments with ringed handles.

FIGURE 2-4. Straight-needle holders.

FIGURE 2-5. Curved (Heaney) needle holder. (Photo courtesy of Aesculap, Inc.)

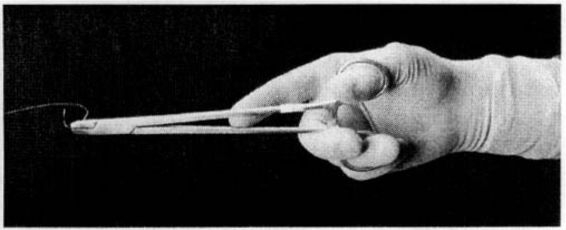

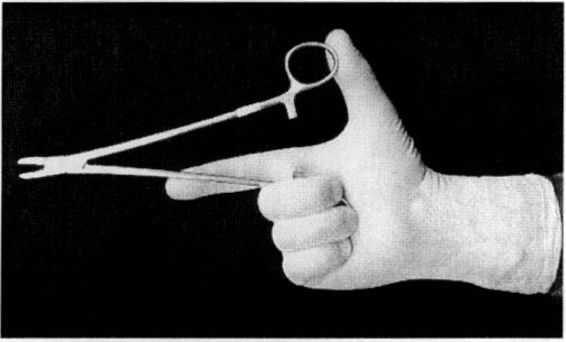

FIGURE 2-6. Technique of grasping the needle holder with the fingers through the rings. Manipulation of the instrument and resetting the needle is awkward using this grip.

FIGURE 2-7. Technique of grasping the needle holder while avoiding fingers through the rings. Manipulation is facilitated by using the instrument without placing the fingers through the rings.

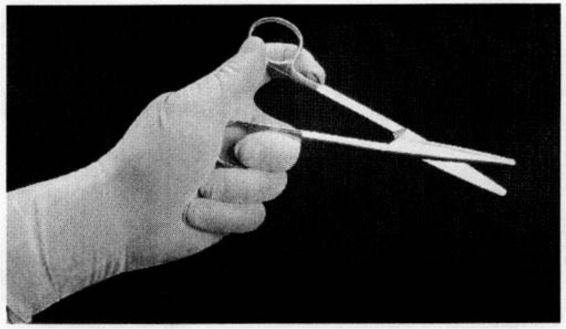

Clamps and scissors are not designed for ambidextrous use. The easy release of a clamp or use of standard right-handed scissors with the left hand therefore requires a different handgrip and technique than when these instruments are used with the right hand. The surgeon should strive to be facile in the use of these instruments with either hand, using the appropriate grip and technique as demonstrated in Figure 2-8.

FIGURE 2-8. Left-handed use of scissors. The same technique is used for left-handed release of clamps.

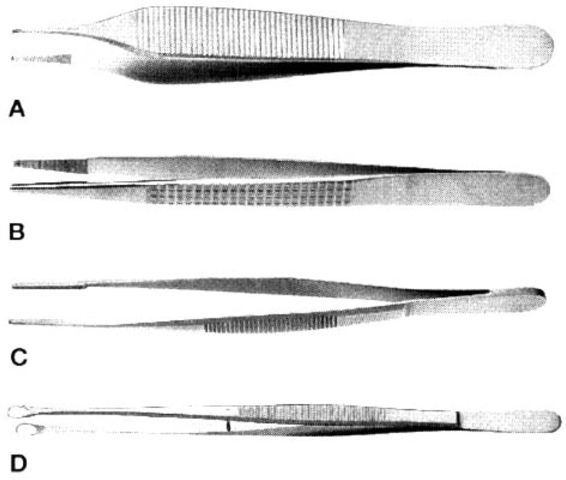

TISSUE-HOLDING FORCEPS

Several types of forceps are commonly used for suture placement (Fig. 2-9). These instruments are available in various lengths. Forceps are designed to grasp tissue, not needles or suture. When needles are grasped with forceps there is a risk of damaging the teeth and the tips of the forceps; when suture is grasped with forceps it decreases its tensile strength.

FIGURE 2-9. Tissue forceps. A. Adson; B. Bonney; C. DeBakey; D. Singley. (Photo courtesy of V. Mueller.)

Dressing forceps are used to handle delicate tissue such as skin, peritoneum, mesosalpinx, or ovary. Tissue forceps have an interlocking tooth-and-socket configuration and are useful in obtaining a firm hold of tougher, relatively avascular tissue such as fascia. DeBakey forceps have a narrow, serrated tip that is ideal for holding delicate tissues such as peritoneum. Singley or Russian forceps have a broad, serrated tip and are most useful in grasping thicker vascular tissues such as myometrium, when the use of a toothed instrument may cause penetration and bleeding.

INSTRUMENTS FOR EVACUATING THE UTERUS

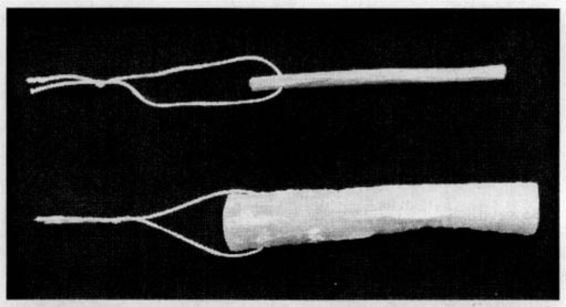

If the cervix requires dilation and urgent evacuation is not necessary, cervical dilation may be initiated by the placement of laminaria. These expand slowly, and the maximum dilation occurs within 6-8 hours (Fig. 2-10). Laminaria japonica is available in diameters from 2 to 6 mm. The largest diameter that passes easily into the cervical canal should be used. If additional dilation is required, multiple laminaria may be inserted simultaneously.

FIGURE 2-10. Laminaria cervical dilator. Top. Prior to insertion. Bottom. Following insertion and fluid absorption.

If manual dilation is required, it should be performed gradually using either Hegar, Pratt, or Hank dilators (Fig. 2-11). These instruments come in graduated diameters and are sized either according to their circumference (eg, French gauge) or their diameter. The formula for determining circumference is C = πD; therefore, the circumference may be divided by π to determine diameter. There is no one cervical dilator that offers a clear-cut advantage; the choice of instrument is based on availability and operator preference.

FIGURE 2-11. Uterine dilators. A. Hegar; B. Pratt; C. Hank. (Photo courtesy of V. Mueller.)

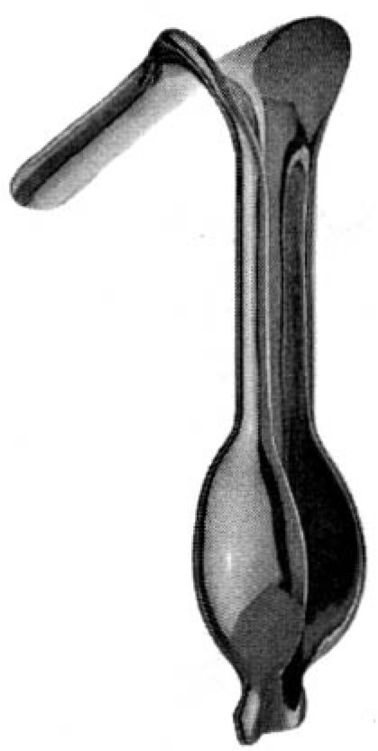

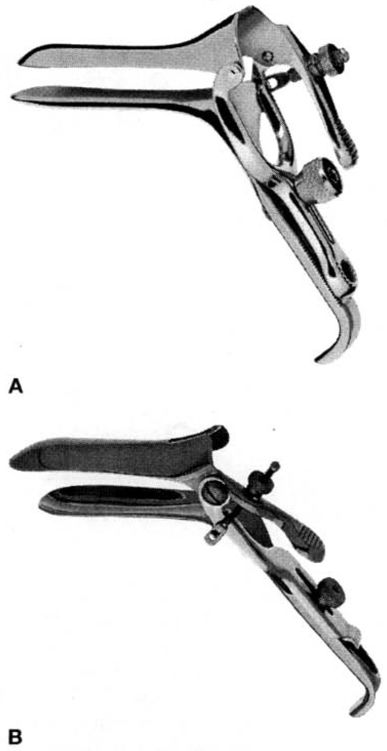

For exposure of the cervix, an Auvard vaginal weighted speculum (Fig. 2-12) is ideal. In some cases, a bivalved Graves speculum (Fig. 2-13) is adequate, but in difficult cases, multiple Breisky-Navratil vaginal retractors (Fig. 2-14) may be helpful. If the cervix is firm and closed, it should be grasped on the anterior lip with a single-toothed tenaculum such as the Barrett or Pozzi forceps (Fig. 2-15). In the postpartum patient, it is preferable to grasp the anterior lip of the cervix with a less-traumatic instrument. A Noto or DeLee cervical grasping forceps, or the more commonly available Foerster sponge forceps (“ring forceps”), is suitable (Figs. 2-16 and 2-17). The Breisky-Navratil vaginal retractors and the sponge forceps are excellent instruments for exposing and repairing cervical tears following delivery and for vaginal placement of cervical cerclage sutures.

FIGURE 2-12. Auvard weighted vaginal speculum. (Photo courtesy of V. Mueller.)

FIGURE 2-13. Vaginal specula. A. Graves; B. Graves, open side. (Photo courtesy of V. Mueller)

FIGURE 2-14. Breisky-Navratil vaginal retractors, assorted sizes. (Photo courtesy of Marina Medical.)

FIGURE 2-15. Pozzi uterine tenaculum forceps. (Photo courtesy of Aesculap. Inc.)

FIGURE 2-16. Noto or DeLee type cervical grasping forceps. (Photo courtesy of Aesculap. Inc.)

FIGURE 2-17. Foerster sponge forceps.

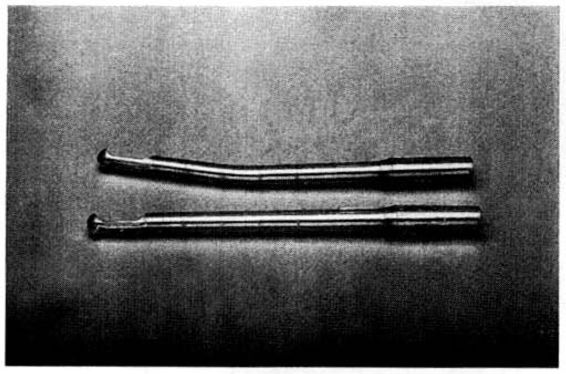

The uterus can be evacuated with suction curettage, sharp curettage, or forceps. Generally, the largest curette that passes easily though the cervix should be selected. Suction is usually supplied by an electric suction pump connected via plastic tubing with an attached swivel handle to the rigid plastic suction curette. Disposable uterine aspiration curettes are available in up to 14-mm diameters (Fig. 2-18). Curettage is usually performed using 60 mm Hg of suction.

FIGURE 2-18. Disposable uterine aspiration curettes, 12 mm (one of assorted sizes). Top. Curved. Bottom. Straight.

DeLee-type ovum forceps facilitate removal of loose tissue from within the uterine cavity (Fig. 2-19). If sharp curettage is required, it may be performed with a sharp uterine curette; larger curettes may be more suitable for managing postpartum hemorrhage caused by retained placental tissue (Fig. 2-20).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree