Figure 6-3

Tinea corporis In some cases, tinea corporis presents with concentric rings (Fig. 6-3). Definitive diagnosis depends on mycologic culture of the scale from a lesion. In cases of candidiasis, tinea imbricata and favus, the causative organism can frequently and confidently be guessed correctly. In general, one may say that Microsporum canis, Microsporum audouinii, T tonsurans, and T schoenleinii can infect scalp and hairless skin, and Trichophyton rubrum and Candida albicans can infect hairless skin and nails.

Figure 6-4

Tinea corporis-vesicular On rare occasions, a marked inflammatory response to the presence of a dermatophyte leads to a vesicular or bullous eruption. The clinical presentation seen in Fig. 6-4 must be differentiated from acute contact dermatitis, bullous impetigo, or an autoimmune blistering disease such as linear IgA dermatosis.

Figure 6-7

Tinea corporis (faciei) Infection at the sites shown in Fig. 6-7 may also be termed tinea faciei. Note the ring shape of the active periphery of the lesions in this patient.

Figure 6-8

Facial lesions may be due to T tonsurans, T rubrum, or T mentagrophytes. Cutaneous infection with zoophilic species, such as M canis, may also occur on the face. As noted in Fig. 6-8, this usually results from close contact with a household pet.

Figure 6-10

In some patients, the occurrence of fungal infection in locations such as the ear may make it difficult to appreciate the ring morphology of the lesion, and thus lead to misdiagnosis as atopic or contact dermatitis. In that situation, the application of topical steroid creams will make the infection worse.

Figure 6-14

In this case of tinea incognito, the patient applied a topical corticosteroid, previously prescribed for atopic dermatitis, to an undiagnosed ringworm infection on the face. The papules and nodules develop when fungal elements penetrate the hair follicle and cause a deeper infection. This form of infection, termed Majocchi granuloma, may also occur on the legs of adolescent girls, where it is spread by shaving.

Figure 6-15

Tinea capitis Fungal infections of the scalp are extremely common in children. The diagnosis of tinea capitis should be entertained in any child in whom patches of incomplete alopecia, crusting, or scaling are found in the scalp. In previous decades, M canis and M audouinii were the most common pathogenic fungi infecting the scalp. The latter frequently causes a discrete grayish patch of hair loss, as shown in Fig. 6-16.

Figure 6-16

In most parts of the United States and in many other parts of the world, T tonsurans is now the predominant organism causing tinea capitis. In the United States, this form of tinea capitis is seen almost exclusively in African-American children. In some children, this dermatophyte causes discrete and dramatic areas of hair loss studded by the stubs of broken hair, so-called black-dot ringworm (Fig. 6-18).

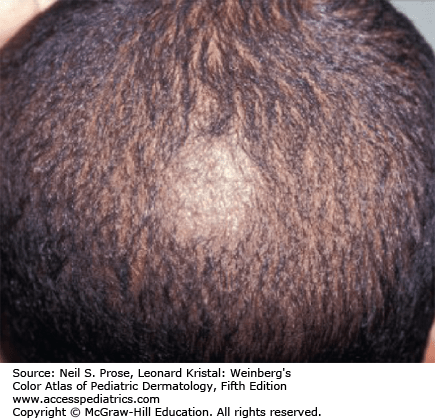

Figure 6-17

Tinea capitis Because T tonsurans does not fluoresce, the Wood’s light is no longer of use in most cases. However, diagnosis can be confirmed by the use of either potassium hydroxide preparation or fungal culture. Pictured here is a child with significant scaling and hair loss due to infection with T tonsurans. There is also a small circular lesion on the facial skin. Similar lesions may develop on the back and chest and provide a clue to diagnosis.

Figure 6-18

In some cases, there are only small and unimpressive patches of “seborrheic” scale with minimal hair loss or groups of small pustules. Attempts to treat tinea capitis with topical antifungal agents alone are doomed to failure. Oral griseofulvin is the most effective form of therapy. The use of selenium sulfide shampoo may be effective in preventing spread to classmates and siblings.

Figure 6-19

Tinea capitis Figure 6-19 shows an exuberant inflammatory response to T tonsurans. The lesions have spread onto the neck, but the primary source of infection is in the hair follicles in the scalp, and systemic therapy is required.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree