Chapter 108 Substance Abuse

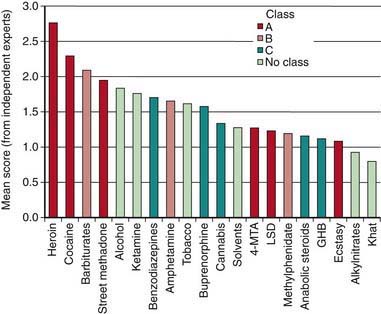

Individuals who initiate drug use at an early age are at a greater risk for becoming addicted than those who try drugs in early adulthood. Drug use in younger, less experienced adolescents can act as a substitute for developing age-appropriate coping strategies and enhance vulnerability to poor decision-making. The first use of the most commonly used drugs occurs before age 18 yr, with 88% of people reporting first alcohol use <21 yr old, the legal drinking age in the USA. Inhalants have been identified as a popular first drug for youth in grade 8. When drug use begins to negatively alter functioning in adolescents at school and at home, and risk-taking behavior is seen, intervention is warranted. Serious drug use is not an isolated phenomenon. It occurs across every segment of the population and is one of the most challenging public health problems facing society. The challenge to the clinician is to identify youths at risk for substance abuse and offer early intervention. The challenge to the community and society is to create norms that decrease the likelihood of adverse health outcomes for adolescents and promote and facilitate opportunities for adolescents to choose healthier and safer options. Recognizing those drugs with the greatest harm, and at times focusing on harm reduction with or without abstinence, is an important modern approach to adolescent substance abuse (Figs. 108-1, 108-2).

Figure 108-2 Protection and risk model for distal and proximal determinants of risky substance use and related harms.

(From Toumbourou JW, Stockwell T, Neighbors C, et al: Interventions to reduce harm associated with adolescent substance use, Lancet 369:1391–1401, 2007.)

Etiology

Substance abuse is biopsychosocially determined (see Fig. 108-2). Biologic factors, including genetic predisposition, are established contributors. Behaviors such as rebelliousness, poor school performance, delinquency, and criminal activity and personality traits such as low self-esteem, anxiety, and lack of self-control are frequently associated with or predate the onset of drug use. Psychiatric disorders are often co-morbidly associated with adolescent substance use. Conduct disorders and antisocial personality disorders are the most common diagnoses coexisting with substance abuse, particularly in males. Teens with depression (Chapter 24), attention deficit disorder (Chapter 30), and eating disorders (Chapter 26) have high rates of substance use. The determinants of adolescent substance use and abuse are explained using a number of theoretical models, with factors at the individual level, the level of significant relationships with others, and the level of the setting or environment. Models include a balance of risk and protective or coping factors that tend to account for individual differences among adolescents with similar risk factors who escape adverse outcomes.

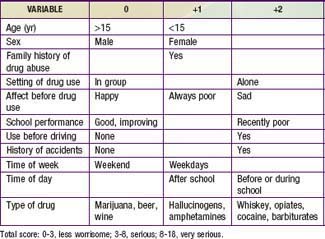

Specific historical questions can assist in determining the severity of the drug problem through a rating system (Table 108-1). The type of drug used (marijuana versus heroin), the circumstances of use (alone or in a group setting), the frequency and timing of use (daily before school versus rarely on a weekend), the premorbid mental health status (depressed versus happy), as well as the teenager’s general functional status should all be considered in evaluating any youngster found to be abusing a drug. The stage of drug use/abuse should also be considered (Table 108-2). A teen may spend months or years in the experimentation phase trying a variety of illicit substances including the most common drugs, cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana. It is not until regular use of drugs resulting in negative consequences (problem use) that the teen typically become identified as having a problem, either by parents, teachers, or a physician. Certain protective factors play a part in buffering the risk factors as well as assisting in anticipating the long-term outcome of experimentation. Having emotionally supportive parents with open communication styles, involvement in organized school activities, having mentors or role models outside of the home, and recognition of the importance of academic achievement are examples of the important protective factors.

Table 108-2 STAGES OF ADOLESCENT SUBSTANCE ABUSE

| STAGE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 |

Epidemiology

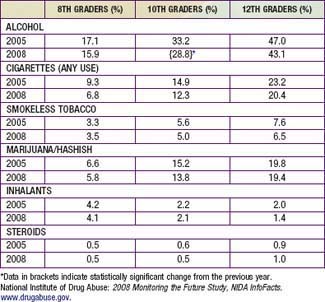

In the USA, alcohol and cigarettes and marijuana are the most commonly reported substances used among teens (Table 108-3). The prevalence of substance use and associated risky behaviors vary by age, gender, race/ethnicity, and other sociodemographic factors. Younger teenagers tend to report less use of drugs than do older teenagers, with the exception of inhalants (in 2008, 15.7% in 8th grade, 12.8% in 10th grade, 9.9% in 12th grade). Males have higher rates of both licit and illicit drug use than females, with greatest differences seen in their higher rates of frequent use of smokeless tobacco, cigars, and anabolic steroids. In school surveys, drug use patterns of Hispanics tend to fall in between whites and African-Americans, with the exception of 12th grade Hispanics reporting highest rates of crack cocaine, heroin (injected), and crystal methamphetamine use. African-Americans report less use of drugs across all drug categories with dramatically lower levels of cigarette use in comparison to whites.

Table 108-3 THIRTY DAY PREVALENCE USE OF ALCOHOL, CIGARETTES, MARIJUANA, AND INHALANTS IN 8TH GRADERS, 10TH GRADERS, AND 12TH GRADERS, 2005 AND 2008

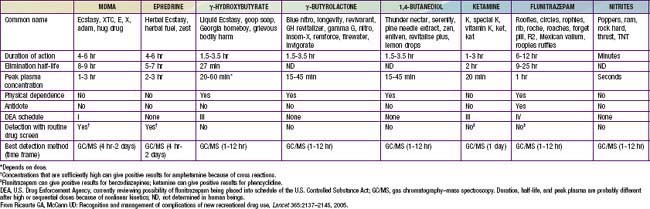

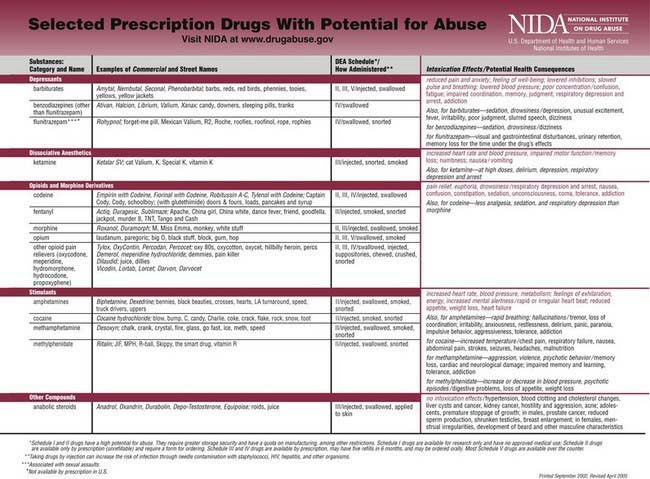

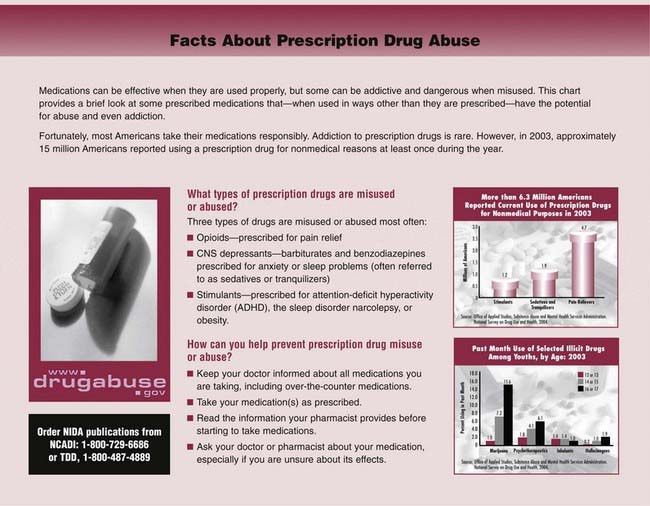

In examining trends in drug use, positive findings are that fewer students reported cigarette, alcohol, or stimulant use than in the previous 5 yr. Marijuana use has leveled off after a general decline. (Past year use of marijuana in 2008: 10.9% in 8th graders, 23.9% in 10th graders, 32.4% in 12th graders.) Prescription drug abuse is increasing in prevalence with 15.4% of high school seniors reported taking a prescription drug nonmedically in the last yr (Table 108-4). For many adolescents and young adults, prescription drug use is the most common abused category of drugs and includes opioids, drugs that treat ADHD, antianxiety agents, dextromethorphan, antihistamines, sedatives, and tranquilizers. Many of these agents can be found in the parents’ home, some are over-the-counter, while others are purchased from drug dealers at schools and colleges. Many users believe that these drugs are benign because they are obtained by prescription or purchased at a pharmacy. Club drugs, commonly used at all-night dance parties, are increasingly popular among older adolescents and young adults (Table 108-5). These drugs have significant side effects especially if taken in combination with alcohol or other drugs. Anterograde amnesia, impaired learning ability, disassociation, and breathing difficulties may occur. Repeated use may lead to tolerance, cravings for the drug, and withdrawal effects including anxiety, tremors, and sweating.

Table 108-4 SELECTED PRESCRIPTION DRUGS WITH POTENTIAL FOR ABUSE

Clinical Manifestations

Although manifestations vary by the specific substance of use, adolescents who use drugs often present in an office setting with no obvious physical findings. Drug use is more frequently detected in adolescents who experience trauma such as motor vehicle crashes, bicycle injuries, or violence. Eliciting appropriate historical information regarding substance use, followed by blood alcohol and urine drug screens is recommended in emergency settings. An adolescent presenting to an emergency setting with an impaired sensorium should be evaluated for substance use as a part of the differential diagnosis (Table 108-6). Screening for substance use is recommended for patients with psychiatric and behavioral diagnoses. Other clinical manifestations of substance use are associated with the route of use; intravenous drug use is associated with venous “tracks” and needle marks, while nasal mucosal injuries are associated with nasal insufflation of drugs. Seizures can be a direct effect of drugs such as cocaine and amphetamines or an effect of drug withdrawal in the case of barbiturates or tranquilizers.

Table 108-6 THE MOST COMMON TOXIC SYNDROMES

| ANTICHOLINERGIC SYNDROMES | |

| Common signs | Delirium with mumbling speech, tachycardia, dry, flushed skin, dilated pupils, myoclonus, slightly elevated temperature, urinary retention, and decreased bowel sounds. Seizures and dysrhythmias may occur in severe cases. |

| Common causes | Antihistamines, antiparkinsonian medication, atropine, scopolamine, amantadine, antipsychotic agents, antidepressant agents, antispasmodic agents, mydriatic agents, skeletal muscle relaxants, and many plants (notably jimson weed and Amanita muscaria). |

| SYMPATHOMIMETIC SYNDROMES | |

| Common signs | Delusions, paranoia, tachycardia (or bradycardia if the drug is a pure α-adrenergic agonist), hypertension, hyperpyrexia, diaphoresis, piloerection, mydriasis, and hyperreflexia. Seizures, hypotension, and dysrhythmias may occur in severe cases. |

| Common causes | Cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine (and its derivatives 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxyethamphetamine, and 2,5-dimethoxy-4-bromoamphetamine), and over-the-counter decongestants (phenylpropanolamine, ephedrine, and pseudoephedrine). In caffeine and theophylline overdoses, similar findings, except for the organic psychiatric signs, result from catecholamine release. |

| OPIATE, SEDATIVE, OR ETHANOL INTOXICATION | |

| Common signs | Coma, respiratory depression, miosis, hypotension, bradycardia, hypothermia, pulmonary edema, decreased bowel sounds, hyporeflexia, and needle marks. Seizures may occur after overdoses of some narcotics, notably propoxyphene. |

| Common causes | Narcotics, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, ethchlorvynol, glutethimide, methyprylon, methaqualone, meprobamate, ethanol, clonidine, and guanabenz. |

| CHOLINERGIC SYNDROMES | |

| Common signs | Confusion, central nervous system depression, weakness, salivation, lacrimation, urinary and fecal incontinence, gastrointestinal cramping, emesis, diaphoresis, muscle fasciculations, pulmonary edema, miosis, bradycardia or tachycardia, and seizures. |

| Common causes | Organophosphate and carbamate insecticides, physostigmine, edrophonium, and some mushrooms. |

From Kulig K: Initial management of ingestions of toxic substances, N Engl J Med 326:1678, 1992.

Screening for Substance Abuse Disorders

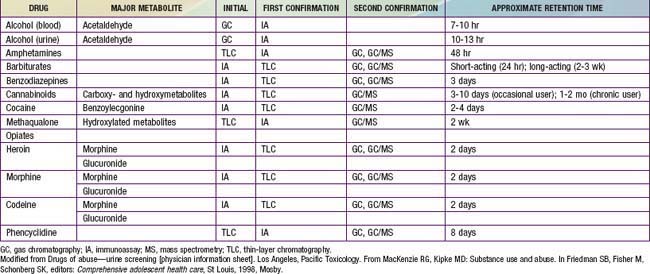

In a primary care setting the annual health maintenance examination provides an opportunity for identifying adolescents with substance use or abuse issues. The direct questions as well as the assessment of school performance, family relationships, and peer activities may necessitate a more in-depth interview if there are suggestions of difficulties in those areas. Additionally there are several self-report screening questionnaires available with varying degrees of standardization, length, and reliability. The CRAFFT mnemonic is specifically designed to screen for adolescents’ substance use in the primary setting (Table 108-7). Privacy and confidentiality need to be considered when asking the teen about specifics of their substance experimentation or use. Interviewing the parents can provide additional perspective on early warning signs that go unnoticed or disregarded by the teen. Examples of early warning signs of teen substance use are change in mood, appetite, or sleep pattern; decreased interest in school or school performance; loss of weight; secretive behavior about social plans; or valuables such as money or jewelry missing from the home. The use of urine drug screening is recommended when select circumstances are present: (1) psychiatric symptoms to rule out co-morbidity or dual diagnoses, (2) significant changes in school performance or other daily behaviors, (3) frequently occurring accidents, (4) frequently occurring episodes of respiratory problems, (5) evaluation of serious motor vehicular or other injuries, and (6) as a monitoring procedure for a recovery program. Table 108-8 demonstrates the types of tests commonly used for detection by substance, along with the approximate retention time between the use and the identification of the substance in the urine. Most initial screening uses an immunoassay method such as the enzyme-multiplied immunoassay technique followed by a confirmatory test using highly sensitive, highly specific gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. The substances that can cause false-positive results should be considered, especially when there is a discrepancy between the physical findings and the urine drug screen result. In 2007 the American of Academy of Pediatrics released guidelines that strongly discourage home-based or school-based testing.

Table 108-7 CRAFFT MNEMONIC TOOL

Adapted from Anglin TM: Evaluation by interview and questionnaire. In Schydlower M, editor: Substance abuse: a guide for health professionals, ed 2, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2002, American Academy of Pediatrics, p 69.

Diagnosis

Substance abuse is characterized by a maladaptive pattern of use indicated by continued use despite serious consequences or physical harm. Chemical dependence can be defined as a chronic and progressive disease process characterized by loss of control over use, compulsion, and the establishment of an altered state where one requires continued administration of a psychoactive substance in order to feel good or to avoid feeling bad. Diagnosing substance abuse rests on the realization that all children and adolescents are at risk but that some are at substantially more risk than others. Specific diagnostic codes are assigned to substance abuse and substance dependence (Table 108-9). These criteria are used in adults and have limitations in use with adolescents due to differing patterns of use, developmental implications, and other age-related consequences; an additional adolescent-sensitive set of criteria specifically for diagnostic use has not been developed. Adolescents who meet diagnostic criteria should be referred to a program for substance abuse treatment unless the primary care physician has additional training in addiction medicine.

Table 108-9 DSM-IV-TR DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR SUBSTANCE ABUSE AND SUBSTANCE DEPENDENCE

SUBSTANCE ABUSE: A maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinical significant impairment of distress as manifested by one or more of the following criteria:

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

Prevention

Preventing drug use among children and teens requires prevention efforts aimed at the individual, family, school, and community levels. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) has identified essential principles of successful prevention programs. Programs should enhance protective factors (parent support) and reduce risk factors (poor self-control); should address all forms of drug abuse (legal and illegal); should address the specific type(s) of drug abuse within an identified community; and should be culturally competent to improve effectiveness. See Table 108-10 for examples of risk factors and protective factors within those domains. The highest risk periods for substance use in children and adolescents are during life transitions such as the move from elementary school to middle school, or from middle school to high school. Prevention programs need to target these emotionally and socially intense times for teens in order to adequately anticipate potential substance use or abuse. Examples of effective research-based drug abuse prevention programs featuring a variety of strategies are listed on the NIDA website (www.drugabuse.gov), and on the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention website (www.prevention.samhsa.gov).

Table 108-10 DOMAINS OF RISK AND PROTECTIVE FACTORS FOR SUBSTANCE ABUSE PREVENTION

| RISK FACTORS | DOMAIN | PROTECTIVE FACTORS |

|---|---|---|

| Early aggressive behavior | Individual | Self-control |

| Lack of parental supervision | Family | Parental monitoring |

| Substance abuse | Peer | Academic competence |

| Drug availability | School | Anti–drug use policies |

| Poverty | Community | Strong neighborhood attachment |

From National Institute on Drug Abuse: Preventing drug use among children and adolescents. A research based guide for parents, educators, and community leaders. NIH publication No. 04-4212(B), ed 2, Bethesda, MD, 2003, National Institute on Drug Abuse.

108.1 Alcohol

Alcohol is the most popular drug among teens. By 12th grade, close to 75% of adolescents in U.S. high schools report ever having an alcoholic drink, with 24% having their first drink before age 13 yr; rates are even higher among European youth. Multiple factors can affect a young teen’s risk of developing a drinking problem at an early age (Table 108-11). Moreover, 30% of high school seniors admit to combining drinking behaviors with other risky behaviors such as driving or taking additional substances. Binge drinking remains especially problematic among the older teens and young adults. Thirty-six percent of high school seniors report having 5 or more drinks in a row in the last 30 days. Teens with binge drinking patterns are more likely to be assaulted, engage in high risk sexual behaviors, have academic problems, and acquire injuries than those teens without binge drinking patterns.

Table 108-11 RISK FACTORS FOR A TEEN DEVELOPING A DRINKING PROBLEM

FAMILY RISK FACTORS

INDIVIDUAL RISK FACTORS