14.2 Stridor

Stridor

Physiological principles

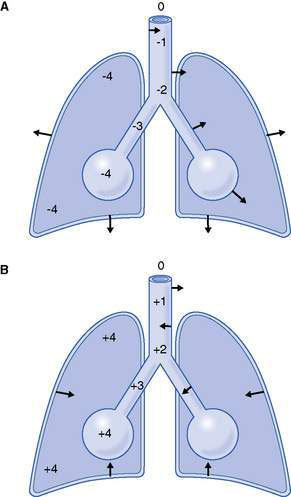

During breathing, there are pressure gradients between the airway opening and the alveoli. Inspiration occurs when alveolar pressure is lowered below atmospheric pressure and air flows in to equalize the pressures. At the onset of expiration, alveolar pressure exceeds atmospheric pressure and air flows out. There are also pressure gradients across the airway wall and these tend to alter airway calibre. The pressure around the extrathoracic airways, that is, those above the thoracic inlet, is atmospheric, whereas the pressure around the intrathoracic airways essentially is equal to the pleural pressure. As illustrated in Figure 14.2.1, the pressure gradients across the airway wall during inspiration means that there is a net force tending to narrow the extrathoracic airways and to dilate the intrathoracic airways (Fig. 14.2.1A). During expiration, the direction of the forces is opposite, resulting in a tendency to narrow intrathoracic airways and dilate extrathoracic airways (Fig. 14.2.1B).

Differential diagnosis

• Age of onset. A stridor present from the first few days of life suggests a congenital or structural cause.

• Speed of onset of symptoms. Infective causes such as croup tend to come on quickly; however, most cases of congenital or structural stridor commonly first present following a viral upper respiratory illness.

• Progression of stridor. Stridor increasing in severity over weeks to months suggests a progressive lesion, such as subglottic haemangioma.

• Effect of body position. Stridor that is worse when lying supine is seen commonly with laryngomalacia.

• Presence of an expiratory component. This suggests a more severe obstruction that limits flow during expiration as well as during inspiration.

• Quality of voice. Although the voice is frequently normal, a hoarse voice would suggest a vocal cord lesion.

• Other medical conditions that could contribute to the pathogenesis or presentation: febrile illness, ex-premature infant, gastro-oesophageal reflux, cutaneous haemangiomas, Möbius syndrome (a very rare syndrome characterized by congenital palsy of the external rectus and facial muscles, usually bilateral, associated with paralysis of the sixth and seventh nerves).

Characteristics of the more important causes of stridor

Laryngomalacia

• a long, curled (sometimes called omega-shaped) epiglottis collapsing during inspiration so that the lateral walls touch, restricting the free passage of air (Fig. 14.2.2A)

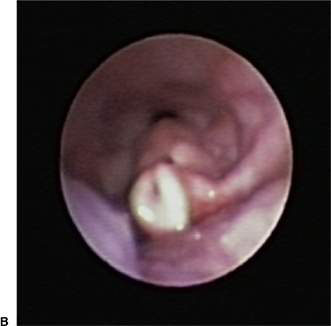

• floppy arytenoid processes prolapsing into the glottic aperture during inspiration (Fig. 14.2.2B)

• a long epiglottis collapsing against the posterior pharyngeal wall during inspiration.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree