Streams of Development: The Key to Developmental Assessment

Frederick B. Palmer

Arnold J. Capute*

*Deceased.

The neurodevelopmental disabilities are diverse but related clinical syndromes of chronic neurologic dysfunction. They can be considered best under the broad and frequently overlapping categories of cerebral palsy, mental retardation, communicative disorders (including the autism spectrum disorders), and neurobehavioral disorders. The syndromes are grouped together because of similarities in presentation, natural history, and traditional treatments, not because of common etiologies. The common thread is the existence of nonprogressive central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction, which results in a functionally significant disruption of the otherwise expected typical sequences of infant and child development.

PEDIATRICIAN’S ROLE IN MANAGING NEURODEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

The pediatrician’s role in managing neurodevelopmental disabilities must include but transcend the provision of general

health care. This expanded role includes responsibilities for detection, developmental diagnosis, developmental monitoring, and coordination of developmental services. It requires familiarity with local health, educational, early intervention, social, and other resources. It requires a working knowledge of local intervention program eligibility standards, changing funding options, and other practical issues influencing access to services, especially in a managed-care setting in which the primary-care pediatrician is central in obtaining access to appropriate services. The pediatrician also must recognize family, cultural, and community factors that may influence development or affect efforts to diagnose and treat disability.

health care. This expanded role includes responsibilities for detection, developmental diagnosis, developmental monitoring, and coordination of developmental services. It requires familiarity with local health, educational, early intervention, social, and other resources. It requires a working knowledge of local intervention program eligibility standards, changing funding options, and other practical issues influencing access to services, especially in a managed-care setting in which the primary-care pediatrician is central in obtaining access to appropriate services. The pediatrician also must recognize family, cultural, and community factors that may influence development or affect efforts to diagnose and treat disability.

The detection or recognition that a child has delayed or atypical development has been a traditional pediatric role because of the almost universal contact with the infant and the family during the first few years of life. Attention to developmental progress should be part of every well-child encounter. Sick-child visits or hospitalizations also offer the opportunity to elicit developmental concerns from caregivers, and these concerns can be explored at later encounters.

The detection of developmental abnormalities can be achieved only partially by a recognition of the risk factors associated with concurrent or subsequent neurodevelopmental disability. Few risk factors have an extremely high likelihood of poor neurodevelopmental outcome. Most factors are unlikely to be associated with disability in an individual child. Moreover, many infants who develop disabilities have no clear history of risk. In most cases, therefore, detection relies on the recognition of neurodevelopmental abnormality—usually a delay in one or more developmental streams.

Developmental screening tests have been used widely in pediatric practice for years. They are not at the same time highly sensitive and specific for neurodevelopmental abnormality, and they do not yield an acceptably small number of false-positive results. That is, a high number of infants with disability, mostly those with milder disabilities, are not detected; some infants without disability are inaccurately designated as having a delay or disability. These are major difficulties, especially when negative screening test results lead to pediatrician complacency and no further efforts at detection, or when frustration with test validity leads to an abandonment of systematic developmental surveillance. The pediatrician should take a broader clinical approach to developmental detection, rather than solely relying on published screening measures.

Developmental diagnosis includes a delineation of the specific neurodevelopmental disability—cerebral palsy, mental retardation, communication disorder, or neurobehavioral disorder—and a quantitation of its severity. A complete developmental diagnosis must recognize the overlaps among these diagnoses. For example, mental retardation and cerebral palsy can coexist, or the child with mental retardation can have an additional expressive language disorder. Other associated disabilities, such as neurobehavioral problems (e.g., deficits in attention), seizures, orthopedic abnormalities, sensory dysfunctions, or growth abnormalities, must be identified. A complete developmental diagnosis usually requires information from other specialists in medical and nonmedical disciplines, which is usually best compiled by and interpreted for the parents by the pediatrician.

Developmental monitoring and coordination of services often can be accomplished by the pediatrician because of his or her orientation as a generalist and experience in dealing with families, schools, and other community agencies. Particularly for younger infants and children, in whom all the manifestations of a neurodevelopmental disability may not yet be clear, the pediatrician must not abdicate this responsibility to other professionals, such as teachers or therapists.

DEVELOPMENTAL STREAMS AND THEIR ASSESSMENT

For the pediatrician to fulfill these roles adequately, a general framework for developmental assessment is necessary. (The framework summarized in this chapter is expanded on in Chapters 98 and 396.) For decades, pediatricians have separated the complex developmental processes into separate developmental streams for easier evaluation. These developmental streams, including language, visuomotor skills, gross and fine motor skills, social development, and self-help, are best analyzed separately. An analysis of each should focus on detecting delay and deviancy.

Developmental delay is best quantitated by the developmental quotient: DQ = developmental age/chronologic age × 100. In children with nonprogressive CNS abnormalities (e.g., static encephalopathies), it represents the rate of development in the measured stream. It provides only a rough guideline for measuring progress. Because it implies a constant rate of development from birth, it should be used with caution after CNS injury acquired during infancy and childhood and when a progressive neurologic process may be present. A language or visuomotor quotient of less than 80 should be seen as frank delay, but a gross motor quotient of less than 50 is generally necessary before ultimate motor disability is likely.

Developmental deviancy, a subtle sign of CNS abnormality, refers to atypical development within a single stream, such as developmental milestones occurring out of normal sequence (e.g., infant who walks before crawling—often associated with mild central hypotonia). Deviancy is useful in detecting mild abnormalities within a given stream if overt delay is not apparent. A recognition of the dissociations between rates of development in different streams is essential for the early diagnosis of atypical development within a specific stream.

COGNITIVE ASSESSMENT

Language

The best single measure of cognitive development in infancy and childhood is language development. Traditional psychologic testing relies heavily on language in its determination of an intelligence quotient, beginning in the preschool years and extending through school age and into adulthood. This is true as early as the third year of life, for which the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Test remains the most commonly used instrument. The Wechsler Scales, the most frequently used intelligence tests in the school years and adulthood, also emphasize the use of language. Infant developmental scales, such as the Bayley Scales of Infant Development and the Cattell Infant Intelligence Test, make less use of language items as measures of developmental progress. However, infant language can be used as an objective tool for early assessment, if professionals are familiar with language markers, their occurrence in typical children, patterns of delay and deviance, and limitations in their use.

The pediatric assessment of early language relies almost entirely on milestones. These prelinguistic and linguistic milestones are related to later cognitive development, and a recognition of early language delay is the most sensitive indicator of subsequent mental retardation or communication disorder. Subtle manifestations of language delay or deviancy indicate the risk for school-aged learning disability and general academic underachievement.

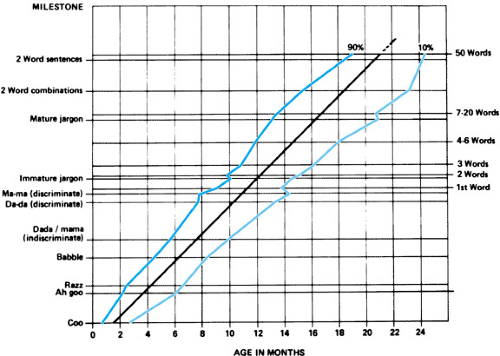

The assessment of infant expressive language development begins in the prelinguistic phase with the sequential occurrence of cooing, babbling, indiscriminate “dada” and “mama,” and

the discriminate “dada” and “mama,” followed by the child’s first true word at approximately 1 year of age. With the development of words used spontaneously and with clear meaning, the child enters the linguistic phase. Between 12 and 24 months, an accelerating increase in vocabulary size occurs, which continues through the school years; it is easily measured up to approximately 2 years of age. Similarly, the increase in phrase length occurs with the sole use of single words to approximately 20 months of age, followed by development of two-word phrases, short sentences, and eventually near-normal adult syntax by the late preschool years.

the discriminate “dada” and “mama,” followed by the child’s first true word at approximately 1 year of age. With the development of words used spontaneously and with clear meaning, the child enters the linguistic phase. Between 12 and 24 months, an accelerating increase in vocabulary size occurs, which continues through the school years; it is easily measured up to approximately 2 years of age. Similarly, the increase in phrase length occurs with the sole use of single words to approximately 20 months of age, followed by development of two-word phrases, short sentences, and eventually near-normal adult syntax by the late preschool years.

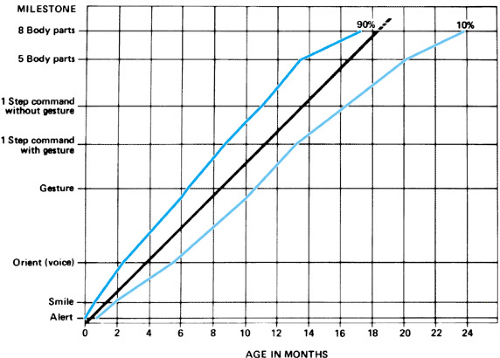

Receptive language development can be traced into the prelinguistic phase of the first several months of life. The earliest receptive language skills are neurosensory. They represent peripheral auditory functioning and the CNS response to sound. The normal newborn alerts to sound by crying, quieting, or otherwise changing state, and by startling, blinking, or by other recognizable responses. By 4 months of age, the child orients to voice by turning to the source of the sound.

Delay in achieving this 4-month skill of auditory orienting may indicate hearing loss, but it may also indicate CNS dysfunction, as seen in mental retardation or communication disorders. It may indicate that the child’s receptive language abilities are not yet at the 4-month level. By 9 months of age, the child should indicate his or her understanding of interactive gesture games by participating in them. He should follow a single-step command accompanied by gesture at 12 months and without gesture by 15 months. At 15 months, he should begin to point to body parts on request, and by 2 to 2.5 years of age, the child should be able to follow a series of two independent commands.

The development of the social use of language, or pragmatics, also should be followed. Abnormalities in pragmatic language are a core feature of autism spectrum disorders. Recognizing such abnormalities early is important in the detection of autism spectrum disorders. During the first 2 years of life, children with autism show poor eye contact, poor linking of eye gaze with gesture and vocalization, little or no pointing to objects, and difficulties in shifting their focus of attention based on others’ use of eye gaze or gesture. Infants with autism also may show less babbling and less interest in verbal or gestural mimicry.

The pediatrician should be able to detect language delay associated with mild mental retardation or moderate communication disorders (language DQ 50 to 80) by the age of 2 years. Many autism spectrum disorders can be detected by 24 to 30 months. To detect milder communication disorders and subtle delays in language, further assessment by a speech pathologist or psychologist is required, although atypical or deviant language development may have been noticed in the early months of life.

Language delay is best identified by determining the child’s level of consistent language performance by milestone criteria, expressing it as a language age, and dividing by the chronologic age to yield a language quotient. A language quotient of less than 80 is regarded as delayed. Previously attained milestones should be converted into language quotients to evaluate the consistency of the rate of development expressed as those quotients. Information can be recorded on graphs, as in Figures 97.1 and 97.2. A “line of best fit” drawn through individual points on this graph represents a developmental rate expressed as the language quotient. This graphic approach allows for the

easy recognition of changes in the developmental pattern, such as plateauing or loss of skills, which may indicate a progressive neurological disorder or process, and may require systematic evaluation by a subspecialist (e.g., child neurologist, pediatric geneticist).

easy recognition of changes in the developmental pattern, such as plateauing or loss of skills, which may indicate a progressive neurological disorder or process, and may require systematic evaluation by a subspecialist (e.g., child neurologist, pediatric geneticist).

FIGURE 97.2. Receptive language milestones; ninetieth and tenth percentiles for a normative population (see legend for Fig. 97.1). (Reproduced with permission from Capute AJ, Palmer AJ, Shapiro BK, et al. Clinical linguistic and auditory milestone scale: prediction of cognition in infancy. Dev Med Child Neurol 1986;28:762.) |

Infants with milder degrees of language impairment may not have overt delay. Their language abnormalities may be reflected as deviant or atypical attainment of milestones. For example, there may be a dissociation between receptive language development and expressive language development, with language understanding at a significantly higher level than language expression, a rather common finding in preschoolers with communication disorders. Another common but less easily recognized phenomenon is a better single-word vocabulary than connected language ability. The child may have an age-appropriate expressive vocabulary, but she is unable to put these words together into phrases and sentences at the similar developmental level suggested by vocabulary size. This can be manifested as an uncoupling of the milestones that normally occur together, such as two-word phrases and a 25-word vocabulary or two- to three-word sentences and a 50-word vocabulary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree