On successfully completing this topic, you will be able to:

recognise circumstances in which spinal trauma is likely to occur

understand the importance and techniques of spinal immobilisation

identify and evaluate spinal trauma.

Introduction

In the context of this chapter, spinal injuries refer to injuries to the bony spinal column, the spinal cord or both. There can be an injury to the bony spine without injury to the spinal cord, but there is significant risk of cord injury in these circumstances.

Failure to immobilise a patient with a spinal injury can cause or exacerbate neurological damage. Failure to immobilise a patient with an injury to the bony spine (without cord injury at that stage) can cause avoidable injury to the spinal cord. Evaluation of the spine and exclusion of spinal injuries can be safely deferred, as long as the patient’s spine is protected.

A spinal injury should always be suspected:

in falls from a height (however it is possible to injure the spine in a fall from a standing position, e.g. fall due to a convulsion)

in vehicle collisions, even at low speed

when pedestrians have been hit by a vehicle

where persons have been thrown

in sports field injuries, e.g. rugby

in a person with multiple injuries

in a person with injury above the clavicle (including the unconscious patient – 15% of unconscious patients have some form of neck injury)

in the conscious patient complaining of neck pain and sensory and/or motor symptoms

in drowning victims.

Persons who are awake, sober, neurologically normal and have no neck pain are extremely unlikely to have a cervical spine fracture. However, neurosurgical or orthopaedic opinion should always be sought if an injury is suspected or detected.

The cervical spine is more vulnerable to injury than the thoracic or lumbar spine.

Approximately 10% of patients with a cervical spine fracture have a second associated noncontiguous fracture of the vertebral column. Hence, if a cervical spine fracture is diagnosed, other spinal fractures should be suspected.

Immobilisation techniques

If injury to the spine is suspected, the whole spine should be immobilised until examination, radiography and supplementary radiological investigations have excluded spinal injury. Injury can only be excluded by an orthopaedic, neurosurgical or a suitably skilled Emergency Medicine doctor. Immobilisation should be carried out by maintaining the spine in the neutral position.

Cervical spine

Immobilisation of the cervical spine is achieved by:

manual inline immobilisation of the head or

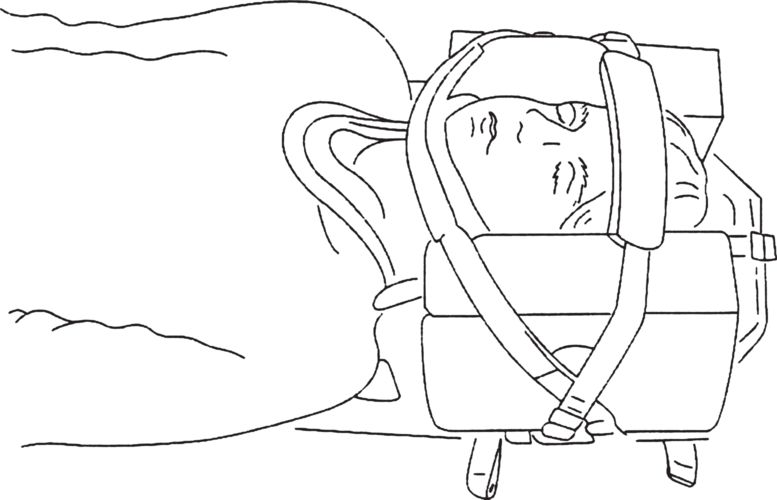

semi-rigid cervical collar plus blocks on a backboard (which may be a headboard or full spine board and straps, see Figure 18.1); collars are correctly sized by following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Thoracic and lumbar spine

The thoracic and lumbar spine should be immobilised by a long spine board. Inadequate, or even prolonged, immobilisation with a spine board has its own complications, with the possibility of worsening any injury and the risk of pressure sores if prolonged immobilisation is undertaken. Hence, the long backboard is usually a transportation device. Early assessment by neurosurgeon or orthopaedic surgeon is undertaken to allow removal from the device. If this is not feasible the injured patient should be log-rolled every 2 hours while maintaining spinal integrity.

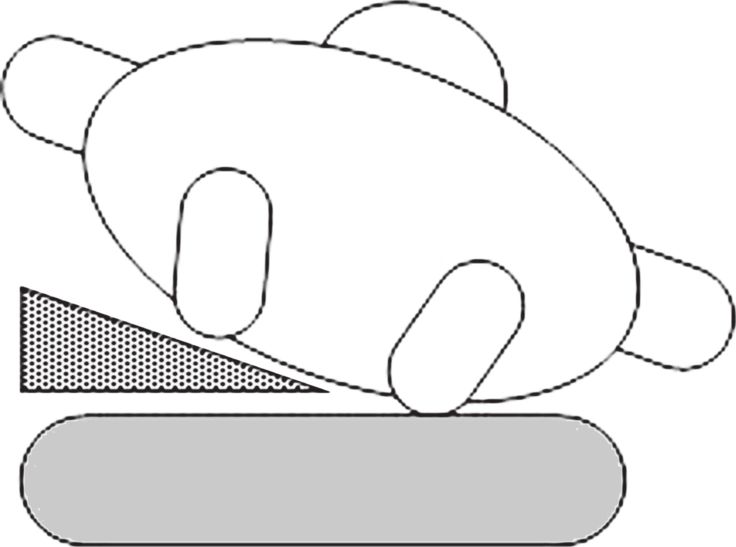

To avoid supine hypotension in the heavily pregnant patient, the right hip should be elevated to 10 to 15 cm with a wedge (Figure 18.2) and the uterus displaced manually. If a pelvic fracture is suspected, manual displacement of the uterus is recommended, rather than elevation of the hip. Alternatively, the whole patient can be tilted to the left, if on a long spine board, by putting a wedge under the board.

Evaluation of a patient with a suspected spinal injury

Spinal injuries may cause problems that are identified in the primary survey, affecting airway, breathing or circulation, or the injury may itself be identified during the secondary survey.

Spinal assessment

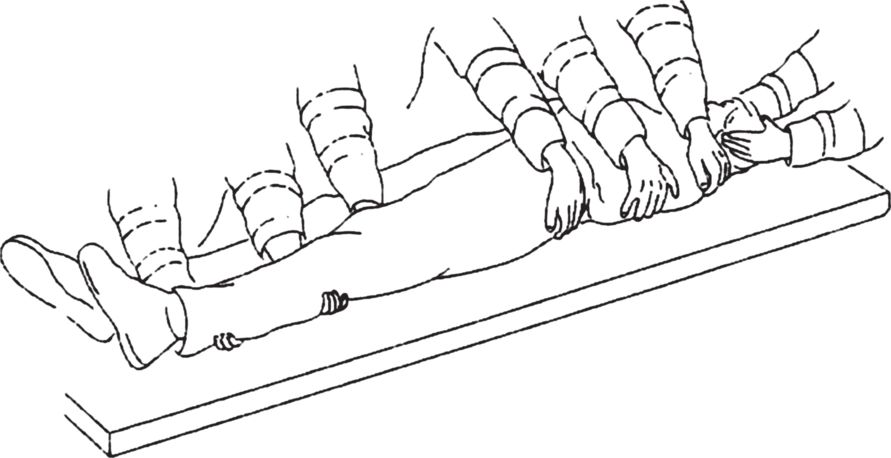

A log-roll must be performed and is illustrated in Figure 18.3. This is a coordinated, skilled manoeuvre by trained personnel. At least four persons are required to perform this: one to maintain manual inline mobilisation of the patient’s head and neck, one for the torso, with two for the hips and legs, with the leader at the head directing the procedure; in order to turn the patient from the supine to the lateral position without causing damage to the spinal cord.

Look for bruising, deformity and localised swelling of the vertebral column. Palpate for localised tenderness or gaps between spinous processes. At this point it may be appropriate to carry out a per rectum examination if clinically indicated.

Neurological assessment

Of the many tracts in the spinal cord, the three that can be assessed clinically are:

corticospinal tract: controls muscle power on the same side of the body and is tested by voluntary movement and involuntary response to painful stimuli

spinothalamic tract: transmits pain and temperature sensation from the opposite side of the body and is tested generally by pinprick

posterior columns: carry position sense from the same side.

Each can be injured on one or both sides.

If there is no demonstrable sensory or motor function below a certain level bilaterally, this is referred to as a complete spinal injury. If there is remaining motor or sensory function with some loss this is an incomplete injury (better prognosis). Sparing of sensation in the perianal region may be the only sign of residual function. Sacral sparing is demonstrated by the presence of sensation perianally and/or voluntary contraction of the anal sphincter.

An injury does not qualify as incomplete on the basis of preserved sacral reflexes, e.g. bulbocavernous or anal wink.

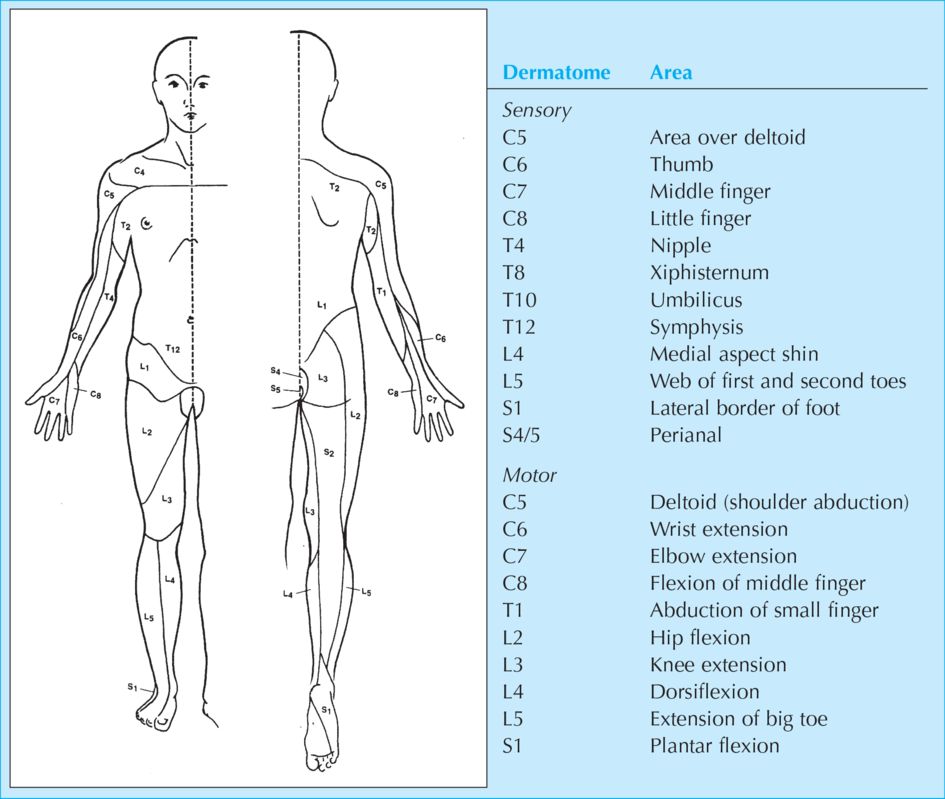

The neurological level is the most caudal segment with normal sensory and motor function on both sides. For completeness, the main dermatomes are given in Figure 18.4.