Shoulder instability

Nonoperative treatment

Indications

Contraindications

First-time dislocator in skeletally immature child (under age 14)

Recurrent, painful, and/or disabling dislocations

MDI – initial management

For patients with posterior instability, immobilization in external rotation for a period of approximately 6 weeks, along with a lengthy course of physical therapy, is generally recommended before an arthroscopic stabilization is considered. External rotation may be accomplished by use of an external rotation orthosis, such as a gunslinger brace, or in a shoulder spica cast. Botulinum toxin injection to the internal rotators may also be considered.

Therapy Recommendations

Physical therapy aimed at rehabilitating weak structures around the shoulder is the preferred initial treatment for first-time dislocators and patients with MDI. A gradual strengthening program follows a period of immobilization. Children with instability can be very challenging to treat, and therefore it is recommended that the affected child work with a therapist experienced in pediatric shoulder instability. Children with demonstrable instability need to be retrained to avoid maneuvers which subluxate or dislocate their glenohumeral joint. Biofeedback is another critical skill for these children to be trained in to achieve successful nonoperative management, and therapists with experience in biofeedback are best equipped to serve these patients. An emphasis on scapulothoracic mechanics is also critical for pediatric and adolescent patients with glenohumeral instability. In addition, maximizing strength in general around the shoulder is beneficial to improve stability.

Outcomes of Nonoperative Treatment for Glenohumeral Instability

Nonsurgical treatment of skeletally mature adolescents sustaining anteroinferior, traumatic dislocation results in a 75–95 % rate of redislocation (Deitch et al. 2003; Hovelius et al. 1996; Marans et al. 1992; Postacchini et al. 2000). Highly variable redislocation rates have been reported following nonsurgical treatment of skeletally immature patients, but multiple series have demonstrated lower recurrence rates for skeletally immature patients compared to their skeletally mature counterparts. In general, instability may be self-limited in skeletally immature children. Coupled with appropriate nonoperative treatment it often resolves, and higher functional outcomes have been reported in patients treated nonoperatively than those undergoing stabilization (Cordischi et al. 2009).

Operative Treatment of Shoulder Instability

Indications

Recurrent, debilitating and/or painful subluxation or dislocation episodes are clear indications for operative stabilization. Inabilities to perform activities of daily living or to participate in athletics are also indications for surgical management. Recurrent instability despite a course of nonoperative management is another scenario when operative treatment should be considered. A first-time traumatic dislocation in an adolescent, skeletally mature individual is a relative indication for surgical stabilization due to the high rate of recurrent instability with nonoperative treatment. If the athlete desires to complete the current season of competition, then nonoperative treatment may be selected until the athlete is ready to compete, and surgical stabilization may be performed at the conclusion of the season.

Open Bankart repair results in similar functional outcomes and redislocation rates compared with arthroscopic stabilization. Advantages of arthroscopy include improved visualization of the entire glenohumeral joint, smaller and more cosmetic incisions, and less surgical dissection. While redislocation rates for pediatric patients undergoing Bankart repair have been reported to be higher than their adult counterparts (Bottoni et al. 2002; Jones et al. 2007), the redislocation rates are substantially lower than those observed with nonoperative treatment (Bottoni et al. 2002).

Contraindications

A diagnosis of Ehlers-Danlos, or a similar connective tissue disorder, is a relative contraindication to surgical treatment. The possibility of this diagnosis should be considered when children with instability are encountered. Children with demonstrable or voluntary dislocation as well as patients with psychological disorders or secondary gain issues are contraindicated for surgery. Poor compliance with physical therapy and nonoperative treatment of instability may correlate with an inability to comply with postoperative restrictions and rehabilitation. The postoperative plan should be discussed with the patient and family preoperatively, and perceived willingness to follow postoperative instructions should be assessed. If the child does not appear to be capable of postoperative restrictions and therapy instructions, then it may be necessary to delay surgery until the child is more mature and able to comply with the physicians’ instructions. Postoperative shoulder spica casting is occasionally utilized when the surgery cannot be delayed and the patient cannot be relied upon.

Anesthesia: General anesthesia is recommended for most pediatric and adolescent shoulder arthroscopy. In older adolescents, the use of an interscalene block may also be considered.

Setup and Positioning

The beach chair position and lateral decubitus position are standard options for arthroscopic shoulder surgery. For smaller children, the lateral decubitus is clearly preferable, because positioning and securing the cervical spine and legs can be difficult with a small child on a standard bed (Fig. 1). In addition, some arthroscopists find it easier to perform intra-articular procedures such as labral repair with patients in the lateral decubitus position. The lateral position also reduces the risk of hypotension and cerebral hypoperfusion that has been reported in the beach chair position (Liguori et al. 1998; Pohl and Cullen 2005). A beanbag, axillary roll, and pillows are used to position and pad the child when the lateral decubitus position is selected.

Fig. 1

The lateral decubitus position is preferred for most pediatric and adolescent shoulder arthroscopy. Traction is applied to place the arm in 30–40° of abduction with slight forward flexion, and a traction boom is utilized to create 10–15 lb of longitudinal traction (Image courtesy of Joseph Abboud, MD)

Traction: Traction is used sparingly in pediatric and adolescent shoulder arthroscopy. It can increase strain across the physis and can also lead to brachial plexus neuropraxia. When the lateral decubitus position is employed, gentle traction is generally set at 10–15 lb in 30° of abduction and slight flexion. Greater abduction can improve visualization of the glenohumeral joint, but it may also increase strain on the brachial plexus.

Equipment: A standard 4.0 mm 30° arthroscope is used for most pediatric shoulder arthroscopic procedures. Cannulas are placed in the shoulder to pass instruments and suture, and these range in diameter from 3 to 8 mm. Other standard arthroscopic instruments such as shavers, burrs, graspers, retrievers, suture passers, Cobb elevators, rasps, knot pushers, and suture cutters should be available. Small suture anchors, typically ranging between 2 and 3 mm, are used for labral repair, rotator cuff repair, and capsulorrhaphy in the pediatric shoulder.

Portal placement: As children and adolescents vary significantly in size, it is important to tailor portal placement to each individual patient. Placing portals at predefined distances from known landmarks may work in adults, but is less reliable in pediatric patients. Insufflating the joint with normal saline prior to portal placement is helpful to distend the joint and allows for safer and easier insertion of the initial trochar. Particular care must be taken to avoid injury to the humeral physis with camera and instrument placement, since damage to the physis can lead to growth disturbance. Generally speaking, work in the pediatric shoulder is facilitated by creating larger distances between portal sites as compared to adults. This increased spacing avoids overcrowding in the pediatric shoulder. Common options for portal sites to be used in pediatric and adolescent shoulder arthroscopy are as follows:

1.

Posterior portal: this is typically the first portal established and is used, at least initially, as a viewing portal. In general, it is recommended to place this portal in the palpable “soft spot” of the posterior shoulder in the interval between the infraspinatus and teres minor. This is located medial and inferior to the posterolateral border of the acromion. Some surgeons begin by injecting normal saline into the glenohumeral joint with a spinal needle. A #11 scalpel is used to create a 5 mm skin incision. The trochar and blunt obturator are directed toward the coracoid. The surgeon’s opposite hand can be used to palpate the coracoid during trochar placement. The obturator is placed between the humeral head and the glenoid, and a “pop” is felt when the obturator penetrates the capsule. If the joint was previously insufflated, removal of the obturator should be accompanied by an egress of fluid from the shoulder.

2.

Anterior central portal: an outside-in technique is performed by placing a spinal needle from the anterior shoulder just lateral to the tip of the coracoid into the glenohumeral joint under direct visualization to localize this portal. The spinal needle, and subsequently the cannula, is placed in the center of the triangle formed by the upper border of the subscapularis, the long head of the biceps, and the anterior labrum. This is an important working portal for many arthroscopic procedures.

3.

Anteroinferior portal: a spinal needle is similarly used to localize this portal, which comes into the shoulder just above the subscapularis. This portal is typically used as a working portal in conjunction with an anterosuperior portal for Bankart repairs and capsulorrhaphy.

4.

Anterosuperior portal: an outside-in technique is also used to create this portal. The cannula is placed just anterior to the long head of the biceps tendon. This portal serves as a viewing portal and accessory portal during Bankart repairs.

5.

Superolateral portal: This portal is used in lieu of an anterosuperior portal for Bankart repair in smaller adolescents. The spinal needle used to localize this portal comes in just lateral to anterolateral corner of the acromion, and it comes into the joint just posterior to the long head of the biceps tendon at the anterior edge of the supraspinatus.

Other considerations: It is recommended to strictly minimize the use of electrocautery devices and any instruments that heat up the fluid in the shoulder during shoulder arthroscopy, particularly in skeletally immature patients. Heated fluid can produce physeal (Moon et al. 2012) and articular chondrocyte damage (Mead et al. 2012). In addition, avoid placing local anesthetic and/or corticosteroids into the pediatric shoulder to prevent damage to the physis and cartilage (Chu et al. 2010; Baron et al. 1992). A fluid pump system is used with pressure set to 30 mmHg.

Techniques

Examination under anesthesia: All patients undergoing shoulder arthroscopy should be examined under anesthesia. Load and shift test is performed to assess shoulder translation and instability. The most common direction of instability is anteroinferior. The grading for this is 0–3+ as described above. The sulcus test is performed by stabilizing the scapula and applying an inferiorly directed traction on the humerus to evaluate the space between the humeral head and acromion. The humerus is then externally rotated with the arm at the side. If inferior laxity is noted on the sulcus test, and this does not improve with external rotations, then tightening the rotator interval may be considered to improve stability concomitant with the labral repair.

A jerk test is helpful to assess for posterior instability. The arm is abducted to 90° and internally rotated. The examiner axially loads the humerus in line with the axis of the scapula. As the arm is horizontally adducted, the examiner will feel the humeral head slide off the posterior glenoid if the shoulder is posteriorly unstable.

Range of motion is assessed in forward elevation, as well as internal and external rotation with the arm at the side and at 90° of abduction. These findings are compared to the contralateral side. A medially healed Bankart lesion is strongly suspected when a decrease in passive external rotation with the arm at 90° of abduction exists as compared to the contralateral shoulder (Deutsch et al. 2006).

Diagnostic arthroscopy. All patients undergoing an arthroscopic shoulder surgery should receive a standard diagnostic evaluation. In a methodical fashion, the long head of the biceps, including the biceps-labral complex and superior labrum, the undersurface of the supra- and infraspinatus, the axillary recess, posterior labrum, glenoid, humeral head, anterior and inferior labrum, inferior glenohumeral ligament complex, anterior capsule, middle glenohumeral ligament, and subscapularis, is examined. In the setting of anteroinferior instability, particular attention is paid to the anteroinferior labrum, and the space between the labrum and glenoid is palpated with a probe. In addition, the axillary recess is inspected for a HAGL lesion, which occurs with relatively greater frequency in skeletally immature patients. The subacromial space usually does not need to be entered in pediatric patients, although in adolescent throwers it is warranted to inspect the bursal surface of the rotator cuff.

Procedure 1: Arthroscopic Bankart Repair

Preoperative considerations for equipment and setup are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

Preoperative planning checklist for arthroscopic Bankart repair

Arthroscopic Bankart repair for anteroinferior glenohumeral instability |

|---|

Preoperative planning and case checklist |

OR table: Standard OR table |

Positioning: Lateral with beanbag |

Traction boom positioned at the bottom of the bed. 10–15 lb of traction with the arm in 30° of abduction and slight flexion |

Equipment |

Arthroscopic irrigation and pump system |

4.0 mm 30° arthroscope |

Three cannulas (camera, 8 mm cannula for anteroinferior portal, 6 mm cannula for anterosuperior portal) |

Arthroscopic rasp/elevator, tissue grasper, suture passing/shuttling device, suture retriever, knot pusher |

2–3 mm suture anchors (typically 2–3 anchors) |

Portals: In larger adolescents, a posterior viewing portal is used along with an anteroinferior working portal and anterosuperior accessory portal. For smaller patients, however, overcrowding can occur with two anterior portals, thereby increasing the difficulty of the procedure. For these patients, a superolateral portal is used as the viewing portal, while the posterior portal is used as an accessory portal, and the anterior portal is the working portal.

Special considerations: Arthroscope and instrument size are based on the child’s size. Even if the surgeon is able to gain access to the joint of a smaller patient, there may not be adequate working space to accomplish the goals at hand.

Arthroscopic Anterior Stabilization Overview

There are many different specific techniques to perform an arthroscopic Bankart repair, and while there is some variation in the specific instruments used, the principles and steps for all techniques are similar. Posterior, anteroinferior, and anterosuperior portals are typically used in performing arthroscopic Bankart repair. The surgical steps in this text (Table 3) describe the use of these three portals. In smaller children, however, simultaneous anteroinferior and anterosuperior portals can create crowding, and therefore a superolateral viewing portal is created in lieu of the anterosuperior portal. When performing an arthroscopic Bankart repair in smaller children where the combination of posterior, lateral, and anterior portals are used, the superolateral portal is the viewing portal, the posterior portal is the accessory portal, and the anterior portal is the working portal. Labral repair is accomplished with suture anchor fixation in the glenoid rim. The labrum may be secured to the glenoid with simple sutures, mattress sutures, or a luggage tag technique (Fig. 2). Traditional or knotless anchors may be used. When arthroscopic knots are tied, the post limb and knots are placed on the capsule and are kept away from the glenoid rim to avoid suture abrading the humeral head. The technique below describes the use of simple sutures with traditional suture anchors.

Table 3

Surgical steps for arthroscopic Bankart repair

Arthroscopic Bankart repair for anteroinferior glenohumeral instability |

|---|

Surgical steps |

Establish posterior portal followed by the anteroinferior portal/cannula just superior to the rolled upper border of the subscapularis |

Establish a third portal. For smaller children, a superolateral viewing portal is established, and the camera is moved into this position. For larger adolescents, an anterosuperior cannula is placed anterosuperior to the long head of the biceps |

Drill followed by anchor placed through anteroinferior portal. The anchor is placed up on the margin of the glenoid face (Fig. 5). Start with the most inferiorly planned anchor |

Suture retriever through anterosuperior accessory portal to bring both limbs of the suture from the anchor out through this portal |

Suture shuttling instrument is passed through the anteroinferior working portal in the glenoid-labral junction at or just inferior to the level of the anchor. Nitinol wire is deployed |

Retriever is placed through the anterosuperior accessory portal to retrieve the nitinol wire loop and bring it out of the shoulder |

The more anterior suture limb coming out of the anchor is passed through the nitinol loop and secured with a knot |

The shuttling instrument and nitinol wire are backed out of the shoulder through the working portal and the knot is released |

Retriever through the working portal to pull both limbs (now one on either side of the labrum) out through this cannula |

Knot pusher to tie the knot. The anterior limb should be used as the post, and the knot should be secured on the anterior aspect of the labrum |

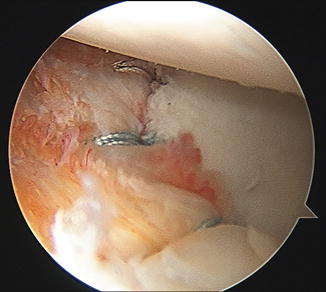

Repeat for additional anchors as needed spaced approximately “one hour” (on a clock face) apart. Typically two to three anchors are used. As the repair proceeds from inferior to superior, the working portal may be changed from anteroinferior to anterosuperior to facilitate placement of the anchor and passage of the suture around the labrum. The completed repair is viewed from the posterior portal (Fig. 6) as well as the anterosuperior portal (Fig. 7) |

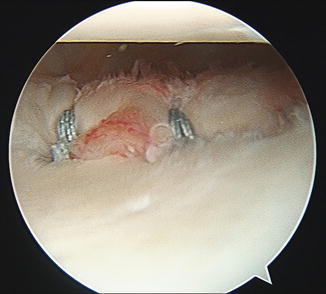

Fig. 2

A loop of high tensile nonabsorbable suture is passed around the labrum to create a “luggage tag.” This suture is incorporated into a knotless suture anchor to secure the labrum to the glenoid with no potential for knot abrasion against the humeral head (Image courtesy of Joseph Abboud, MD)

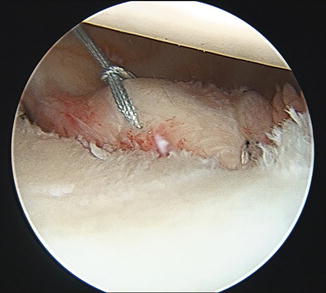

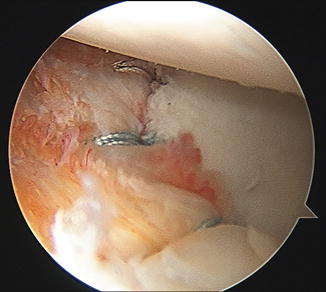

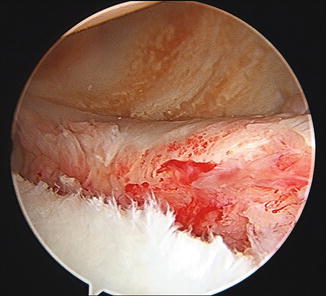

Fig. 3

The Bankart lesion has often migrated medially after the labrum is torn, so a rasp is placed between the labrum and glenoid to mobilize the labrum. The glenoid rim is also prepared to create bleeding bone to increase the potential for labral healing (Image courtesy of Joseph Abboud, MD)

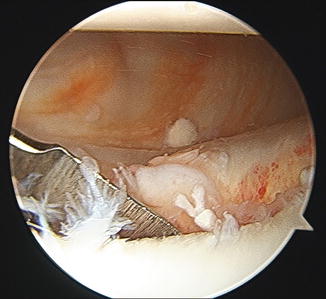

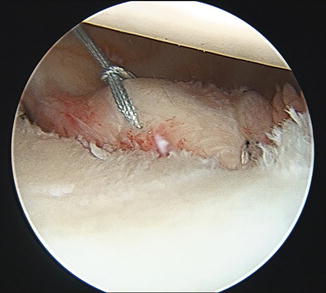

Fig. 4

The labrum has been completely mobilized, and the glenoid rim has been prepared. The surgeon may then proceed with placement of suture anchor and suture around the labrum (Image courtesy of Joseph Abboud, MD)

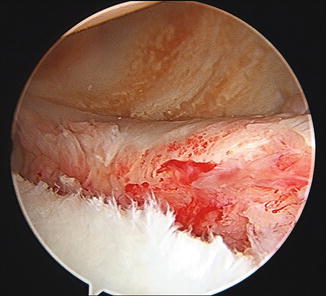

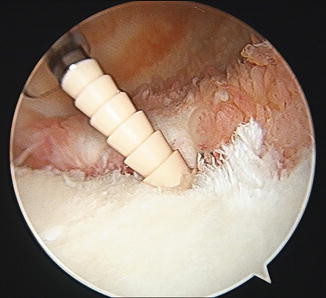

Fig. 5

The suture anchor is placed at the margin of the glenoid rim. In this case, an “anchor first” approach was used. The suture is then passed around the labrum (Image courtesy of Joseph Abboud, MD)

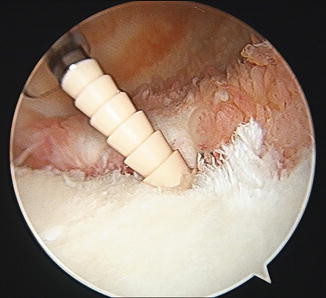

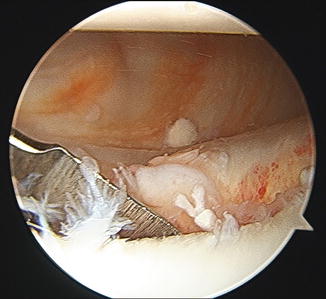

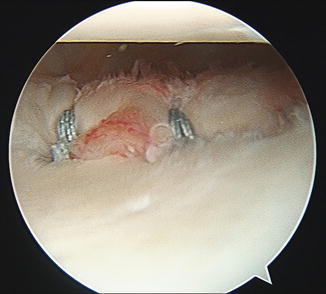

Fig. 6

The completed anteroinferior labral repair is visualized from the posterior portal. In this case, a third suture anchor was also present inferiorly and is not visualized in this image (Image courtesy of Joseph Abboud, MD)

Fig. 7

View from the anterosuperior portal demonstrating three-suture anchor repair in the anteroinferior glenoid rim (Image courtesy of Joseph Abboud, MD)

In cases of concomitant pathologic laxity, or when the labrum is deficient and needs to be reconstructed by using capsular tissue and ligament, an anterior capsulorrhaphy is desired as well. The suture passing device is placed through a small amount of capsule inferior to the anchor before passing it through the glenoid-labral junction to shift the capsule superiorly.

Postoperative Protocol

Therapy and restrictions following Bankart repair begin with a period of no shoulder activity, followed by gradual increases in passive motion. The next phase of rehabilitation is active range of motion and gradual strengthening. Biologic healing occurs at 4 months, and at this time light throwing is permitted. Unrestricted return to all activities and sports is allowed at 6 months postoperatively (Table 4).

Table 4

Postoperative protocol for arthroscopic Bankart repair

Arthroscopic Bankart repair for anteroinferior glenohumeral instability |

|---|

Postoperative protocol |

Week 0–2: Sling with no exercises; no active use of shoulder |

Weeks 2–6: Discontinue sling around the house; add pendulum exercises, passive external rotation to 30°; scapular strengthening. No formal therapy |

Weeks 6–12: Discontinue sling; start formal therapy. Passive stretching, overhead pulley, light strengthening, scapular stabilization and strengthening; may use shoulder actively. Goal for full ROM and full weight bearing by week 10 |

Weeks 12–16: Increase strengthening |

4 months: Further strengthening, activities as tolerated except contact or throwing sports. Light throwing initiated |

5 months: Hard throwing allowed |

6 months: Release to all activities as tolerated including return to contact sports |

Outcomes

At 2–3 years post-stabilization, recurrent dislocation rates for adolescents who underwent an arthroscopic Bankart repair are approximately 0–10 % (Kraus et al. 2010; Bottoni et al. 2002; Jones et al. 2007). High functional outcomes are reported at short- to midterm follow-up (Kraus et al. 2010). While open and arthroscopic Bankart repairs result in similar functional outcomes and redislocation rates, arthroscopic stabilization possesses the advantages of improved intra-articular visualization, smaller and more cosmetic incisions, and less surgical dissection. Although the rates of redislocation in pediatric patients undergoing Bankart repair are higher than their adult counterparts (Bottoni et al. 2002; Jones et al. 2007), these rates are significantly lower than those reported with nonoperative treatment (Bottoni et al. 2002). Table 5 summarizes key surgical tips to optimize surgical outcomes, while Table 6 addresses management of complications.

Table 5

Surgical pitfalls and prevention

Arthroscopic labral repair | |

|---|---|

Potential pitfalls and prevention | |

Potential pitfall | Pearls for prevention |

Recurrent instability | Carefully assess for excess capsular laxity and evaluate for any bone loss. When either is present, they must be appropriately addressed |

Chondrolysis from drill and/or anchor placed on glenoid face central to the glenoid rim | Place drill and anchor on the margin of the glenoid face and ensure that the drill and/or anchor does not migrate during drilling or anchor placement |

Chondrolysis and/or mechanical symptoms from suture knot in the joint and abrading the humeral head chondral surface | Use the suture limb away from the chondral surface as the post |

Take care to secure the knot away from the joint | |

Knotless suture anchors may also be used to prevent this complication | |

Table 6

Management of complications

Arthroscopic labral repair | |

|---|---|

Complication | Management |

Recurrent instability | Assess for bone loss with MRI and/or CT. Consider revision arthroscopic or open repair |

Persistent pain | Evaluate for chondrolysis produced by intra-articular anchor and/or suture placement |

Loss of external rotation | Avoid overtightening the anterior soft tissues. Avoid closing down a physiologic structure such as a sublabral foramen |

Failed repair | Prevent aggressive early motion and activities |

Assessment of Pediatric and Adolescent Rotator Cuff Injuries

Pathoanatomy and Applied Anatomy

Rotator cuff pathology is uncommon in pediatric and adolescent athletes, but in the last few decades, an increase in sports participation and intensity among children and adolescents has led to an increase in the incidence of overuse injuries in overhead throwing athletes (Nordqvist and Petersson 1995). Rotator cuff injuries more often occur in throwing athletes due to repetitive supraspinatus abrasion, but may also be seen following acute traumatic injuries. Multiple theories abound to explain the constellation of shoulder pathology which can be seen in the throwing shoulder . One theory is that during the late cocking and early acceleration phases of throwing, when the arm is maximally abducted and externally rotated, a great deal of stress is placed on the anterior ligaments and capsule of the shoulder. Over time these can attenuate and stretch out, resulting in laxity and instability. This laxity may then lead to impingement of the supraspinatus on the posterosuperior labrum resulting in partial-thickness articular-sided supraspinatus tears (Halbrecht et al. 1999). Posterosuperior labral pathology may also develop from this internal impingement. In addition, compensatory scarring and hypertrophy of the posterior capsule and posterior band of the IGHL can develop, leading to a glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD). A Bennett lesion, which is an ossific lesion in the posteroinferior glenoid, may also develop, and it is associated with posterior labral pathology and articular-sided rotator cuff tears. Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears are generally managed nonoperatively in the pediatric and adolescent patient populations. However, if the tear progresses to a full-thickness tear or if symptoms persist despite conservative treatments, arthroscopic rotator cuff repair may be indicated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree