Short Stature and Growth Hormone Therapy

Douglas G. Rogers

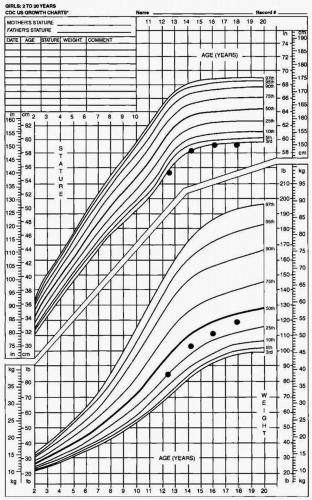

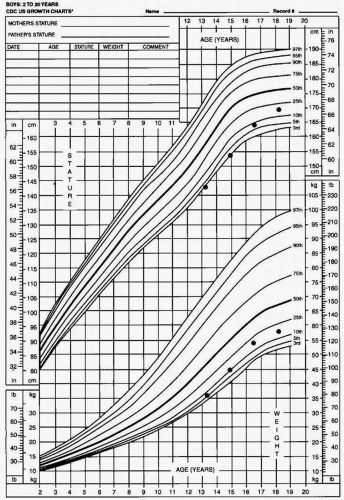

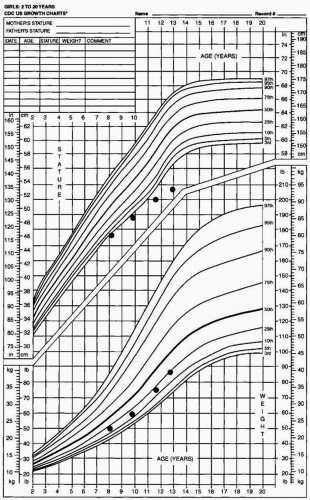

Short stature is a common complaint. Of every 20 children, the height of one will be below the fifth percentile channel on a standard growth curve. Differentiating between normal variations of growth and pathologic conditions that cause short stature can be difficult. The purpose of this chapter is to review the diagnostic evaluation that can differentiate between normal variations and pathologic conditions.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Analysis of the growth curve is critical in the evaluation of a child with short stature. Important information obtained from the growth curve includes:

Absolute height

Growth rate

Ratio of weight to height

Other tools helpful in the evaluation include:

Relative proportions of the lower and upper body segments

Bone age

Although the height of many children is below the fifth percentile channel on a growth curve, in only a few of them is the growth rate also below normal. Measuring a child’s height over a 6-month period of time to determine the growth rate, is the first and most important step in evaluating a child with short stature. Because linear growth normally occurs at a relatively constant rate of between 5 and 7 cm annually after the first 3 years of life, an annualized growth rate of <5 cm is considered abnormal. A normal growth rate, regardless of a child’s height (even if it is below the fifth percentile), is unlikely to be associated with an underlying pathologic condition.

The weight-to-height ratio can help distinguish between endocrine causes (i.e., growth hormone deficiency) of short stature and other chronic conditions that may interfere with growth (i.e., renal or gastrointestinal disease). In general, weight gain is relatively preserved in children with endocrine conditions, whereas it is impaired in those with chronic conditions not of endocrine origin.

An assessment of the relative proportions of the upper and lower body segments can help differentiate conditions that involve both the upper and lower body segments from those that involve one more than the other. Conditions that affect the trunk and lower extremities equally include:

Growth hormone deficiency

Hypothyroidism

Inadequate caloric intake

Gastrointestinal disorders

Chronic renal disorders

Conditions that affect the trunk more than the lower extremities (decreased upper body-to-lower body ratio) include the spondylodysplasias. In contrast, the skeletal dysplasias, such as achondroplasia, are associated with an increased upper body-to-lower body ratio.

The bone age is utilized to assess skeletal maturity. Most conditions associated with a poor growth rate result in delayed skeletal maturation and thus a delayed bone age. A notable exception to this is Cushing’s syndrome which may cause growth failure while the bones continue to mature. A delayed bone age does not indicate a specific diagnosis.

CLINICAL ENTITIES ASSOCIATED WITH NORMAL VARIATIONS IN GROWTH

Children who are short but have a normal growth rate generally exhibit either of two normal growth patterns:

Children with familial short stature characteristically have:

Short parents and a short final adult height

Normal bone age consistent with chronologic age

Normal onset of puberty

Children with constitutional delay of growth characteristically have a:

Delayed bone age

Delayed onset of puberty

Parent(s) in whom puberty may have been delayed

Normal final adult height

PATHOLOGIC CLINICAL ENTITIES CAUSING SHORT STATURE

Once it has been established that a child’s growth rate is subnormal (<5 cm per year), chronic conditions or illnesses that can cause growth failure must be eliminated from the differential diagnosis. Many chronic conditions are associated with growth failure (e.g., congenital heart disease, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anemia, achondroplasia). Most of them can easily be eliminated from the differential diagnosis by means of a careful history and physical examination. However, the manifestations of some chronic conditions or illnesses can be so subtle that they may not be revealed by a thorough history and physical examination. These include:

Turner syndrome (Fig. 19.3)

Growth hormone deficiency (Fig. 19.4)

Cushing syndrome (Fig. 19.5)

Crohn disease (Fig. 19.6)

Celiac disease

Hypothyroidism

Chronic renal disease

Renal tubular acidosis

Hypochondroplasia

Even in patients with subtle manifestations of these conditions, it is frequently possible to ascertain additional historical factors that may pinpoint the diagnosis (Table 19.1). In some cases, growth failure may be the only obvious manifestation; for example, inflammatory bowel disease may result in growth impairment before the gastrointestinal features develop.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree