16 Sexual problems

Normal Sexual Response in Women

What are the characteristics of ‘normal’ sexual response in women?

Women’s sexual response is characterised as highly variable and influenced by a wide range of determinants, including physiological, psychosocial and contextual factors. While aspects of sexual response such as vaginal lubrication and orgasmic contractions are seen to occur in most women who are adequately sexually stimulated, the subjective or emotional aspects of sexual responsiveness are highly individual and subject to learning and cultural factors.1

In different places around the world, female sexuality is viewed very differently: in Western countries women are highly sexualised, especially through the media, whereas in some Asian and African countries the opposite is true. The most extreme example of this is the practice of female genital mutilation, which is used as a means of limiting or controlling sexual pleasure in women. Many cultures and some religions also mandate restrictions over sexual practice during menstruation, pregnancy and/or menopause. There is often no sense of equality in sexuality between men and women. Open communication and discussion of sexual matters is discouraged, and women in these cultures may find it hard to express their sexual needs to their partners or to initiate discussion about sexual difficulties.1

Both of these models assumed linear progression from one phase to the next and did not adequately recognise individual variation or the importance to sexual satisfaction of the subjective experience, environment and stimuli that are conducive to sexual feelings.2 In essence, they ignored the psychosocial components of women’s sexual responsiveness.

A new and refreshingly different model of women’s sexual response cycle has been proposed by Basson (Fig 16.1).3 It is circular and includes multiple sexual and non-sexual reasons for engaging in sex, the psychological and biological influences on arousability, and subjective feelings of arousal and desire.1 According to this model, women frequently enter into a sexual experience through a stance of neutrality with positive motivation for intimacy or relationship. While some may criticise the model as stereotyping women as sexually passive, Basson proposes that rather than initiate sexual activity out of sexual drive, as the traditional model would propose, a woman may instigate physical contact or be receptive to sexual initiation for various reasons, such as the desire for closeness, intimacy and commitment, and as an expression of caring.1

(Modified from Basson4; published with the permission of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists)

Other unique aspects of this model are also worth considering:

Sexual Dysfunction

How is female sexual dysfunction classified?

While an argument could be made that ‘sexual dysfunction’ is in reality a normal or logical response to difficult circumstances (e.g. a problem with the relationship, sexual context or cultural factors),3 the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV)5 has utilised the term ‘female sexual dysfunction’ and subclassifed it into four categories: hypoactive sexual desire disorder, sexual arousal disorder (lubrication), orgasmic disorder and dyspareunia. Some have voiced concern that the classification of female sexual dysfunction has been engineered by the pharmaceutical industry in an effort to create the need for pharmacological intervention.6 There are also other problems inherent in this classification. Loss of desire is not necessarily perceived as problematic for all women and there is little correlation between sexual thoughts and sexual satisfaction.7,8 Additionally, while between 5% and 17%8,9 of women say that they have problems with arousal, there are no objective measures to measure this.10

How commonly do sexual problems present in general practice?

The prevalence of sexual disorders is notoriously difficult to assess, as different instruments provide different answers.11 In a survey undertaken in London general practices,12 22% of men and 40% of women had some form of sexual dysfunction, but only 3–-4% had an entry relating to sexual problems in their general practice notes. Among women with any sexual difficulty, on average, 64% experienced desire difficulty, 35% experienced orgasm difficulty, 31% experienced arousal difficulty, and 26% experienced sexual pain.13 Of the sexual difficulties that occurred for 1 month or more in the previous year, 62–89% persisted for at least several months and 25–28% persisted for 6 months or more.13 Only a proportion of women with sexual difficulty were distressed by it (21–67%).

What are the potential causes of sexual dysfunction in women?

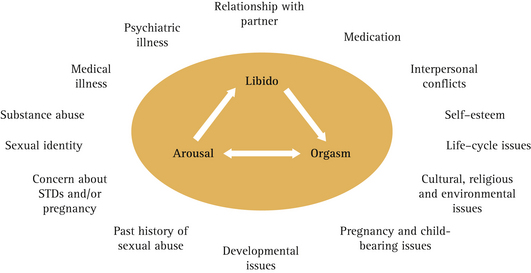

Interpersonal issues and psychological and physiological factors can all contribute to sexual dysfunction (Fig 16.2).3

A national sample of American women found that their emotional relationship with the partner during sexual activity and general emotional wellbeing were the two strongest predictors of absence of distress about sex.7 Contextual factors such as concerns about safety (risks of unwanted pregnancy and STDs, for example, or emotional or physical safety), appropriateness or privacy, or simply that the situation is insufficiently erotic, too hurried, or too late in the day may also contribute to dysfunction.3

Psychological factors associated with sexual dysfunction include low self-esteem, mood instability, tendency towards worry and anxiety14 as well as memories of past negative sexual experiences (such as coercive or abusive ones), and expectations of negative outcomes to the sexual experience (e.g. dyspareunia or partner sexual dysfunction).15

Myths and facts concerning the impact of hormonal factors and medications are outlined in Box 16.1.

BOX 16.1 Myths and facts concerning the impact of hormonal factors and medications on sexual function

How should GPs approach patients with sexual dysfunction?

In recognition of the multiple influences on sexual functioning, it has been suggested that doctors focus on the three factors that contribute to sexual dysfunction: past psychosexual development; current life context; and medical factors, including comorbid illness, drugs and previous surgery.2 It is important to avoid ‘pathologising’ women by diagnosing a sexual disorder where symptoms are a normal response to an external factor.3 Equally important is the identification of issues such as past sexual abuse or past or current intimate partner violence.

The history is the most important part of assessment and diagnosis in sexual dysfunction and should involve questions about the quality of the couple’s relationship, the woman’s mental and emotional health, the quality of past sexual experiences, specific concerns related to sexual activity (such as insufficient non-genital and non-penetrative genital stimulation), and the woman’s thoughts and emotions during sexual activity.10 The partner’s perspective regarding the situation is also important to obtain. Physical examination infrequently identifies a cause of sexual dysfunction but may be helpful when there is associated dyspareunia.10

What are the recommended approaches to the management of sexual dysfunction in women?

The answer to this question really depends on the causative factors. GPs have a central role to play in educating women about the normal variation in women’s sexual response and the factors that affect libido and arousal. This could be achieved by explaining the model given in Figure 16.1 to the woman. For many women, this explanation and reassurance that her symptoms are not due to ‘hormone deficiency’ may be all that is required. Other women may require other interventions.

Psychological interventions

Cognitive behavioural approaches and psychodynamic approaches are used during counselling. It is also helpful to work with the couple when there is loss of sexual desire, as this allows both partners’ understanding of the problem to be examined and differences in sexuality and sexual needs to be explored. While many people expect their partner to have the same sexual needs as their own, counselling aims to encourage acceptance of difference, a concept sometimes described as ‘benign variation’.21 A brief outline of the kinds of psychological therapies that may assist are given in Box 16.2 (p 302).

BOX 16.2 Psychological therapies for sexual dysfunction

(From Basson and Basson10)

Cognitive behavioural therapy

Pharmacological interventions

With the advent of phosphodiesterase inhibitors such as Viagra for the treatment of male sexual dysfunction came the query as to whether such medication would assist women. Large randomised trials of sildenafil in women with arousal and desire disorders, however, showed no improvement in any measure of sexual desire, sensation, lubrication or satisfaction.22

recommend against making a diagnosis of androgen deficiency in women at present because of the lack of a well-defined clinical syndrome and normative data on total or free testosterone levels across the lifespan that can be used to define the disorder. Although there is evidence for short-term efficacy of testosterone in selected populations, such as surgically menopausal women, we recommend against the generalized use of testosterone by women because the indications are inadequate and evidence of safety in long-term studies is lacking.23

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree