On successfully completing this topic, you will be able to:

discuss the pathophysiology of sepsis

identify the septic patient

commence supportive management

arrange appropriate investigations and referral.

Terminologies

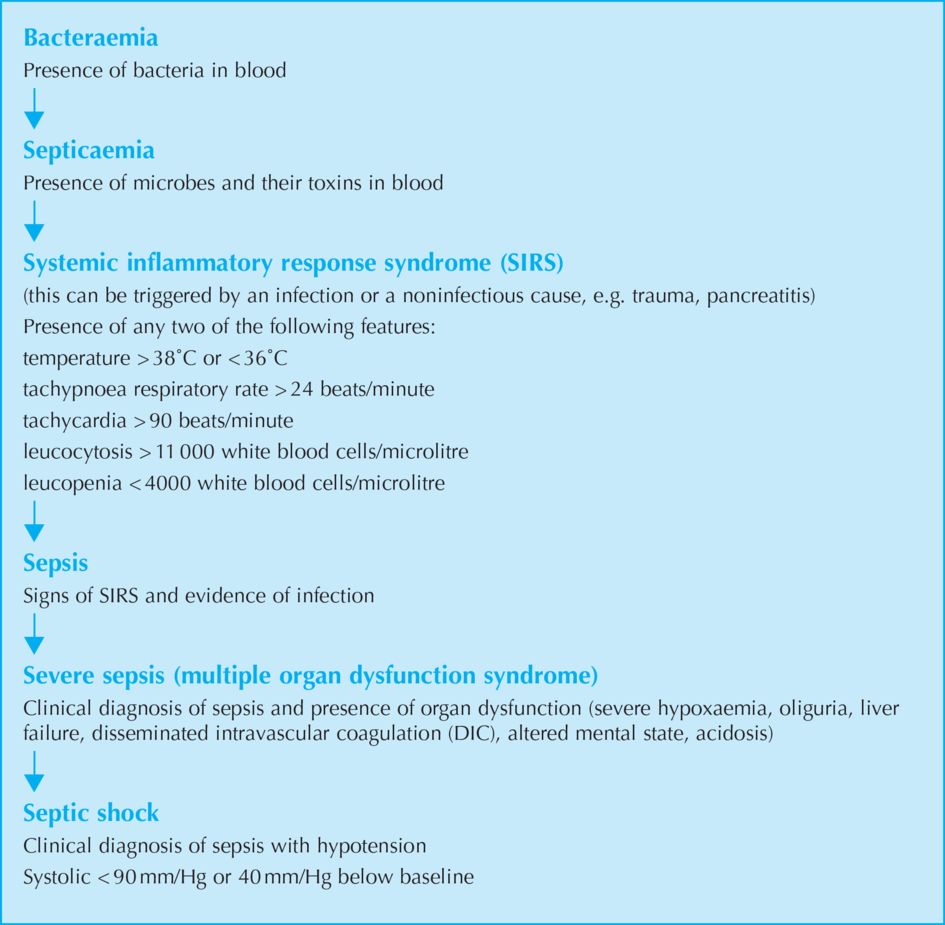

Different terminologies have been used to describe the various manifestations of sepsis; a brief account of these will help in understanding the syndrome. Sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock are terms used to identify the continuum of the clinical response to severe infection (Figure 6.1).

Introduction and incidence

Sepsis is one of the five major causes of maternal morbidity and mortality worldwide. It accounts for 10% of maternal mortality in the developed world. This figure is higher in the developing world as septic abortions are seen more frequently. Pregnant women tend to be young and healthy. Only 0–4% of pregnant women who develop bacteraemia develop septic shock and of these, 2–3% die.

There are specific opportunities to improve the management of the condition. Clinical trials involving new therapeutic interventions have demonstrated, for the first time in 20 years, improved survival in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Improvements in mortality can be made by:

having a high index of suspicion to allow earlier identification/diagnosis of sepsis

adopting agreed standards of care for timely investigation and treatment.

Confidential enquiry deaths

The 2006–08 report Saving Mothers Lives highlighted a worrying increase in deaths from genital tract sepsis and placing it as the leading cause of direct maternal death with 29 deaths. Fortunately this rising trend has reversed and whilst still an important, and the second most common, cause of direct death accounts for 20 deaths from 2009–2012. Timely recognition, fast administration of intravenous antibiotics and escalation of care to involve senior clinicians are key areas for future improvement and education of frontline staff remains a priority. See Box 6.1 for causes of sepsis in obstetric patients.

Microbiology

The most common microbes responsible for sepsis in the UK include Streptococcus Group A, B and D, followed by Escherichia coli. Other organisms that can cause sepsis include Staphylococcus aureus and the obligate anaerobic bacterium, Fusobacterium necrophorum.

Deaths in the latest report were most commonly due to beta-haemolytic Group A Streptococcus. This is not the same organism as the Group B Streptococcus, which is present in the vagina in many women, and may cause neonatal sepsis but is rarely a problem for the mother. Group A Streptococcus is a common skin or throat commensal, carried asymptomatically by up to 30% of the population. It is easily spread and is responsible for streptococcal sore throat, a very common childhood condition. Historically, puerperal fever was much more common prior to the advent of antibiotics and Group A streptococcus was responsible for the majority of infections and deaths.

Transmission in pregnant women is thought to be either through the throat as a portal of entry, or via the perineal route, even in the presence of intact membranes, as bacteria can cross this apparent barrier. Streptococcal infection has a seasonal rise in incidence between December and April. The link between pregnant women and children with Group A streptococcal sore throats is thought to be significant as a possible source of infection. In the past, there was an emphasis on the transmission of infection from caregivers to women, much reduced since the advent of strict hygiene practices in hospitals. It is thought that raising public health awareness of the risks from family members and encouraging women to follow appropriate personal hygiene practices may be helpful in reducing transmission of infection; in particular, pregnant women should be encouraged to handwash both before and after using the toilet to avoid transmitting organisms from other household members.

Other organisms seen in recent confidential reports included: E. coli; Clostridium septicum (a compulsory anaerobe associated with gas gangrene); Streptococcus pneumoniae; Morganella morganii (Gram-negative gastrointestinal inhabitant acting as an opportunistic pathogen and resistant to beta lactam antibiotics) and one case of PantonValentine leucocydin (PVL) toxin producing methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).

Epidemiology

Groups of women over-represented in the deaths due to sepsis are women from minority ethnic groups, including asylum seekers and recent immigrants, as well as obese women. Lack of English language may have been a factor. Three women with sickle cell trait or disease died, suggesting that these women need particular care. Again, these cases were from ethnic minority groups.

The gestation at presentation and route of sepsis has been suggested as a useful method for defining cases for future comparisons, as each group may have differing methods of transmission and therefore prevention:

unsafe abortion

presenting with infection and ruptured membranes (genital tract sepsis)

genital tract sepsis post delivery (including post-abortion/miscarriage)

severe sepsis from the community, membranes intact, not in labour

postpartum sepsis related to delivery but not involving the genital tract

other coincidental infections, e.g. pneumonia.

Pathophysiology of sepsis

Inflammation represents the body’s response to an insult, be it an infection or an injury. The initial response involves the release of primary mediators, interleukin-1 and tumour necrosis factor alpha. These are cytokines produced from activated macrophages. These primary mediators stimulate the production of secondary mediators that, in turn, activate coagulation and complement cascades. This is followed by the expression of anti-inflammatory mediators that help to contain the inflammation locally. This is the period during which there is immunoparesis. As with many other regulatory processes, there is a fine balance between the pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators.

In situations where the bacterial load is high, or there is an imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators, inflammation becomes generalised resulting in severe sepsis. There is growing evidence that this fine balance is genetically controlled.

At a cellular level, the inducible form of nitric oxide synthase is stimulated. This causes overproduction of nitric oxide from endothelial cells, macrophages and muscle cells. Nitric oxide is the major mediator of vasodilatation and myocardial dysfunction, which result in hypotension. Superoxide radicals also react with nitric oxide to form peroxynitrate, which causes direct cellular injury.

Clinical manifestations of haemodynamic alterations

There is a decrease in arteriolar and venous tone. This causes venous pooling of blood and a drop in vascular resistance, resulting in hypotension. In the initial stages of sepsis, there is hypotension with reduced cardiac output and low filling pressures. With fluid resuscitation, cardiac output increases, resulting in a hyperdynamic circulation, but there is not much change in blood pressure owing to a reduced vascular resistance. There is an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance, resulting in raised pulmonary arterial pressures. The changes in the vascular tone differ in different vascular beds, resulting in the maldistribution of blood volume and flow. There is evidence to suggest that the ability of tissues to extract oxygen is impaired owing to mitochondrial dysfunction. This encourages anaerobic metabolism in tissues, promoting lactic acidosis.

Clinical issues and presentation

Sepsis is a complex syndrome that is difficult to define, diagnose and treat. Some of the signs and symptoms are rather vague and there is an overlap with other clinical conditions, such as placental abruption, ectopic pregnancy, influenza and gastroenteritis, resulting in an inappropriate level of clinical response.

Minimising risk from infection in the antenatal period, by avoiding unnecessary vaginal examinations and paying attention to hygiene, may reduce the incidence of sepsis. Early recognition and increased surveillance of those at risk including careful assessment of postnatal mothers, especially those with prolonged rupture of membranes, ragged membranes or possibly incomplete delivery of placenta and women with uterine tenderness or enlargement, will help to identify women developing serious infection.

A high index of suspicion and close surveillance will help in identifying women with early sepsis. There has been concern raised that maternity and community staff, who do not routinely work with sick patients, need to take much greater note of basic medical and nursing observations and care (see also Chapter 4, Recognising the seriously sick patient).

Symptoms may include:

feeling unwell, anxiety or distress

shivery or feverish or pyrexia

sore throat, cough or influenza-like symptoms (pneumonia accounts for a significant number of admissions to ICU in pregnant women)

chest pain

vomiting and/or diarrhoea

abdominal pain or wound tenderness

breast tenderness, suggesting mastitis

headache

unexplained physical symptoms

Serious clinical signs can be categorised as Red Flag signs as suggested by the latest CMACE report Saving Mothers’ Lives see Box 6.2.

These include:

feeling unwell including altered mental state, including unusual anxiety, agitation or reduced conscious level

fever >38°C or hypothermia <36°C can be due to sepsis

breathlessness: respiratory rate >20 can be related to pulmonary pathology or associated with the acidosis which accompanies severe sepsis (see below)

tachycardia: persistently >100bpm

prolonged capillary refill times as a measure of reduced cardiac output and effective peripheral perfusion

hypotension with initially warm vasodilated peripheries, followed by cold extremities in advanced shock

abdominal or chest pain – beware ‘after pains’ of a severity that is out of proportion to known cause and not responding to usual analgesia

uterine or renal angle pain or tenderness

diarrhoea and/or vomiting

if pregnant, reduced fetal movements or an abnormal, or absent, fetal heart beat

spontaneous rupture of membranes or offensive liquor or vaginal discharge

persistent vaginal bleeding may be associated with uterine sepsis

broken down perineum following birth trauma or other signs of sepsis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree