17.1 Seizures and epilepsies

Terminology and classification

The International League Against Epilepsy recognizes two major categories of epileptic seizures, based on clinical and electroencephalographic (EEG) features: focal seizures and generalized seizures. Focal seizures originate within neural networks involving one hemisphere of the brain and are more or less localized at onset, whereas generalized seizures start in and rapidly involve networks in both cerebral hemispheres. Several, pathophysiologically distinct generalized seizure types are recognized by their different clinical and EEG patterns, the most common being tonic–clonic, absence and myoclonic seizures. Focal seizures have common pathophysiological features and are not further classified, but can be distinguished by the region of brain involved and the resultant clinical manifestations; the terms ‘simple’ and ‘complex partial’ are no longer applied to focal seizures according to degrees of impaired consciousness, although this is still an important clinical distinction. Epileptic spasms are not definitively focal or generalized in nature, hence are given a separate category in the current seizure classification (Box 17.1.1).

The conditions that predispose to epileptic seizures (the epilepsies), are best characterized, when possible, by the cause of the particular condition and by the epileptic syndrome. An epileptic syndrome is an electroclinically distinctive condition identifiable on the basis of a typical age of onset, specific EEG findings, seizure types, and often other features that, when taken together, permit a specific diagnosis. The syndrome diagnosis often has implications for treatment, management and prognosis. One practical way of organizing the list of recognized syndromes is by age of onset (Box 17.1.2). Some of the recognized syndromes are known to be due to single-gene mutations, primarily of genes coding for neuronal ion channels. Some epilepsies are due to cerebral or cortical malformation, and others are associated with rare metabolic disorders. Some are due to prenatally or postnatally acquired brain injuries. Unfortunately, the causes of the most common syndromes remain unknown, although a polygenetic basis is most likely.

Box 17.1.2 Epileptic syndromes by age of onset*

Neonatal period and infancy

• Early myoclonic encephalopathy

• Early infantile epileptic encephalopathy with suppression burst (Ohtahara syndrome)

• Epilepsy of infancy with migrating focal seizures

• Benign familial neonatal and infantile epilepsy

• Generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+)

• Infantile epileptic encephalopathy with epileptic spasms (West syndrome)

• Benign myoclonic epilepsy of infancy

Childhood

• Benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (rolandic epilepsy)

• Early-onset benign occipital epilepsy (Panayiotopoulos syndrome)

• Late-onset benign occipital epilepsy (Gastaut type)

• Epilepsy with myoclonic–atonic seizures (Doose syndrome)

• Epilepsy with myoclonic absences

• Childhood epileptic encephalopathy with tonic seizures (Lennox–Gastaut syndrome)

• Autosomal-dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy

• Epileptic encephalopathy with continuous spike-and-wave during sleep

Common epilepsies of infancy, childhood and adolescence

West syndrome

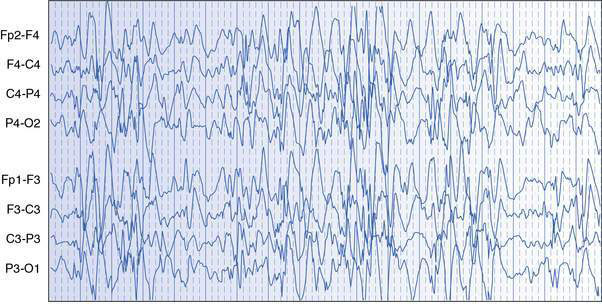

West syndrome, also known as infantile spasms, is the most common and important to recognize severe epileptic syndrome in infancy. The principal seizure type is epileptic spasms, which are essentially brief tonic seizures that typically occur in series over a minute or more, usually many times a day. Onset of spasms is usually between 3 and 8 months of age, and males are affected more often than females. Flexor or salaam spasms are the most common and consist of sudden drawing up of the legs, hunching forward of the neck and shoulders, and flinging out of the arms; opisthotonic or extensor spasms are less common. The EEG usually shows a diffusely disorganized pattern with high-voltage, multifocal epileptic activity, called hypsarrhythmia (Fig. 17.1.1). Development may be delayed prior to the onset of spasms, or there may be loss of visual attention and arrest or regression of development at seizure onset. The developmental regression that occurs in West syndrome is attributable to the epileptic disorder and the condition is therefore considered to be an epileptic encephalopathy. Differential diagnosis includes a variety of normal or benign infant behaviours, such as sleep jerks, colic, shuddering attacks, benign myoclonus of infancy and gastro-oesophageal reflux, as well as other less sinister myoclonic epilepsies of infancy.

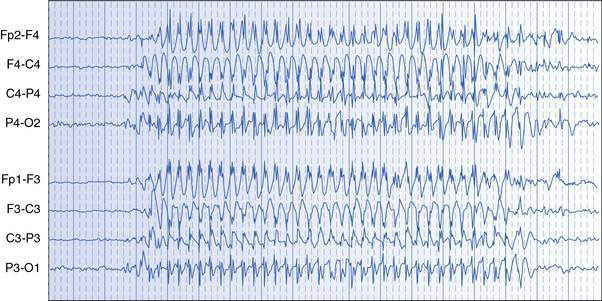

Absence epilepsy

Absence seizures are manifest by sudden cessation of activity with staring, usually lasting only 5–15 seconds. Blinking, upward deviation of the eyes, slight mouthing movements and some fidgeting hand movements (automatisms) may occur. The child is unresponsive, does not fall, is rarely incontinent and returns promptly to normal activity at the offset of the absence, with no memory of the seizure. The EEG shows generalized spike–wave activity during the seizure (Fig. 17.1.2). Usually, many attacks occur in a day. Absence seizures can generally be precipitated in the clinic room and during EEG recordings with hyperventilation. Differential diagnosis of absence seizures includes day-dreaming and focal seizures of temporal lobe origin.