Sedation

Lynne M. Sterni

Mythili Srinivasan

Robert M. (Bo) Kennedy

Goals of sedation include alleviation of procedure-related pain and anxiety, immobility when necessary to complete the procedure, and maintenance of patient safety with limitation of sedation-related complications.

There is an increased need for procedural sedation in pediatrics.

Many procedures and imaging studies require patient cooperation with little to no movement, while others require pain control and the need for reduced anxiety and relaxation.

Because of developmental status and age-related behaviors in children, completing these procedures often requires sedation.

Sedative medications should never be prescribed and administered at home, either before or after the procedure. This is associated with increased risks of respiratory depression and death. It is strongly discouraged by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).

Although many institutions have sedation protocols in place, the safest alternative is a designated pediatric sedation service or unit run by experienced sedation providers trained in airway management and sedation techniques.

Sedations in the emergency department setting are considered “urgent” and should be performed by emergency department providers with training in airway and sedation skills.

Both emergency departments and sedation units should have accessibility to extra personnel in case of adverse events, and availability of providers experienced in advanced airway skills if needed.

During procedural sedation—from the time a sedative drug is administered until the child awakens—continuous monitoring by both electronic monitors and medical providers trained in sedation and pediatric advanced life support is necessary.

Pediatric-sized airway equipment should be readily available, as well as an oxygen source and emergency medications.

Sedation personnel should observe the airway, respiratory, and cardiac status, and vital signs.

They are responsible for managing any sedation-related complications

They should not be performing any significant role in the procedure, so as not to be distracted from the airway and observation of the patient.

When patients who are considered at high risk for sedation complications are encountered, this chapter suggests reasons for involvement of an anesthesiologist.

This chapter is meant to serve as a reference for physicians trained in sedation. It should not be considered all-inclusive of the subject or a substitute for formal sedation training before participating in sedation-related patient care.

DEFINITIONS

The following are definitions from American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), AAP, and Joint Commission (formerly the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations [JCAHO]) guidelines:

Minimal sedation: a drug-induced state during which patients respond normally to verbal commands. Although cognitive function and coordination may be impaired, ventilatory and cardiovascular functions are unaffected.

Moderate sedation/analgesia: a drug-induced depression of consciousness during which patients respond purposefully to verbal commands, either alone or accompanied by light to moderate tactile stimulation. No interventions are required to maintain a patent airway, and spontaneous ventilation is adequate. Cardiovascular function is usually maintained.

Deep sedation/analgesia: a drug-induced depression of consciousness during which patients cannot be easily aroused or respond purposefully following repeated or painful stimulation. The ability to maintain ventilatory function independently may be impaired. Patients may require assistance in maintaining a patent airway, and spontaneous ventilation may be inadequate. Cardiovascular function is usually maintained.

STAGES OF SEDATION AND RECOVERY

Presedation: physical examination, evaluation of medical history and past sedation/anesthesia experiences, sedation plan, and informed consent; gathering of equipment, medications, and obtaining intravenous (IV) access.

Sedation

Induction: administration of sedation/analgesia (higher risk of apnea or laryngospasm at this phase). The sedation provider should not leave the patient’s bedside from this point on.

Maintenance: maintaining a preplanned depth of sedation

This may require additional doses or titration of medications, keeping in mind the length of the procedure (avoid prolonging sedation) and the type of agent needed (analgesia versus anxiolytic/hypnotic).

Continuous monitoring and recording of vital signs every 5 minutes is necessary during sedation.

A sedation score should be recorded every 15 minutes until the patient is ready for discharge or transfer. At St. Louis Children’s Hospital, the authors use the University of Michigan Sedation Scale (see reference by Malviya et al. in Suggested Readings):

0 = awake and alert

1 = minimally sedated: tired/sleepy, appropriate response to verbal conversation and/or sound

2 = moderately sedated: somnolent/sleeping, easily aroused with light tactile stimulation or a simple verbal command

3 = deeply sedated: deep sleep, arousable with purposeful response to significant physical stimulation

4 = unarousable or nonpurposeful response to significant physical stimulation

Emergence: recovering from effects of sedation. The patient should be fully monitored with the provider or sedation credentialed nurse at bedside (higher risk of laryngospasm at this phase).

Recovery

Phase I (deep sedation with recovery score ≥3; see Table 26-1 for Aldrete recovery scoring system). Continuous monitoring and recording of vital signs every 5 minutes is necessary.

Sedation, pain, and recovery scores are documented every 15 minutes.

The transition to phase II recovery begins when the level of consciousness is consistent with moderate sedation (sedation score of 2); the patient is clinically stable and vital signs are at baseline (+/-20%); supplemental O2, airway, ventilation, and cardiovascular support are not required; and the Aldrete recovery score is 8 with pain score of 6 or less.

Phase II (minimal to moderate sedation with sedation score ≤2): recovery provider must be immediately available.

Vital signs and sedation score are recorded every 15 minutes until conclusion of phase II recovery.

Pain and recovery scores are documented at end of phase II recovery.

Noninvasive blood pressure monitoring and electrocardiogram may be waived if they are disruptive to patient and recovery care, provided the vital signs are stable.

Phase II recovery concludes with discharge once standard discharge criteria are met by the patient. Care can be transferred to responsible parent/legal guardian/inpatient care team.

TABLE 26-1 Aldrete Scoring System for Recovery from Sedation* | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Discharge/Transfer Criteria

It is suggested that the following criteria be met before discharge from sedation unit

Vital signs at baseline +/- 20%

No respiratory distress

Spo2 at baseline (+/-3%) or ≥95% on room air

Motor function baseline or sits/stands with minimal assistance

Fluids/hydration normal and no emesis/nausea

Aldrete recovery score ≥9 for discharge, ≥8 for admission to a hospital floor, where monitoring is not one-to-one (see Table 26-1)

Pain score ≤4 for discharge or ≤6 for admission (or pain score reduced 50% postprocedure)

Sedation score ≤1 for discharge or ≤2 for admission; with no naloxone or reversal agents given for 2 hours

It is important to stress to parents that after sedation children should not climb, bathe, or swim alone; be left alone in a car seat; or participate in activities requiring physical coordination for 24 hours.

PRESEDATION EVALUATION

Goals are to identify the difficult airway; assess any cardiac, respiratory, or neurologic risk factors; and prevent sedation complications.

History

The history and physical examination should determine any risks versus benefits of sedation. Problems to be discussed with an attending physician experienced in sedation or anesthesia include concerns regarding the history and physical examination; any patients ASA classes III, IV, or V (see later discussion for ASA classification system); or any patients with cardiopulmonary instability that may worsen with sedation.

Past medical history should focus on systemic conditions affecting sedation outcome:

Cardiac history: congenital heart disease, history of arrhythmias, past radiologic or surgical interventions, current cardiac medications, and blood pressure issues. Address endocarditis prophylaxis if warranted.

Respiratory issues: current or recent upper or lower respiratory infection, history of wheezing, recurrent pneumonia, any respiratory medications/inhalers, history of croup, prematurity or prolonged intubation, chronically enlarged tonsils, obstructive sleep apnea, or any potential airway masses/tumors/hemangiomas.

Gastrointestinal issues: history of gastroesophageal reflux disease, frequent vomiting, motion sickness or prolonged vomiting after prior sedation or anesthesia, history of delayed gastric emptying, gastroparesis, melena, or known gastrointestinal blood loss

Neurologic disorders: Epilepsy—last seizure, seizure frequency and characteristics, typical epileptic rescue treatment, and current anticonvulsant therapy

Neuromuscular disease: degree of respiratory musculature compromise, any cardiac involvement, potential K+ imbalance, history of respiratory disease/infections

Renal disease: potential electrolyte disturbances, decreased renal function significant enough to require changes in medication dosage or dosing intervals, hypoalbuminemia secondary to renal losses, hypertension, dehydration, history of

oliguria or anuria, and need for intermittent bladder catheterization with associated latex sensitivity

Liver disease: hepatic dysfunction that may impact drug metabolism, hepatomegaly that may impact lung tidal volumes, history of esophageal varices or ascites

Hematology/oncology disease:

Most recent complete blood count/electrolytes, last chemotherapy regimen, and any in-situ central lines

Porphyria: if present, avoid barbiturates

Endocrine disease:

Diabetes—current blood glucose level, diabetic medications and last dose, recent electrolytes if hyperglycemic

Thyroid disease—recent TSH and T4, assessment of patient symptoms of hyper/hypothyroidism

Adrenal disease—current medication management and stress dosing requirements

Genetic disease: Many syndromes are associated with cardiac, renal, and metabolic derangements as well as craniofacial/airway abnormalities. Medical conditions of specific syndrome should be reviewed prior to proceeding with sedation.

Importance of past sedation/anesthesia records

Sedation/anesthesia records should be reviewed as available to assess size of endotracheal tubes (ETTs) and laryngoscope blades needed, any difficulty with mask ventilation or intubation, and any adverse medication reactions or unexpected outcomes caused by procedural sedation.

History of postsedation or postoperative nausea or vomiting

Sedative agents used in past (if known) and any complications/parental concerns

Family history of adverse reactions or events during sedation or anesthesia particularly addressing malignant hyperthermia (relevant if using succinylcholine)

Classification Systems

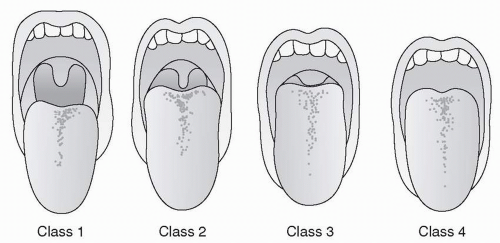

Mallampati Classification System

During presedation evaluation, each patient should be assigned a Mallampati score, with the understanding that each classification is associated with anticipation of an increasingly difficult airway. There are four classes (Fig. 26-1). Class 4 is considered the most difficult.

Mallampati scoring should be done during the physical examination in conjunction with determination of neck mobility, ability to open mouth without temporomandibular joint or jaw pathology, dentition status, mouth and tongue size, and cricoidmandible distance. This is done by asking the child to open the mouth and stick out the tongue as far as possible without use of tongue blades or assistance. Many young children are unable to perform this task.

This helps give the sedation provider an idea of degree of difficulty in managing the airway if mask ventilation or intubation should become necessary.

ASA Physical Status Classification

During presedation evaluation, each patient may be assigned an ASA score to determine the physiologic status of the patient before sedation:

Class I: normal healthy patient with no chronic medical conditions

Class II: patient with a mild to moderate but well-controlled medical condition, such as asthma or diabetes under good control

Class III: patient with severe systemic disease such as cardiac disease with borderline blood pressure control or on inotropes, seizure disorder with frequent seizures

Class IV: patient with severe systemic disease that is life threatening

Class V: moribund patient with little chance of survival; surgery is a last effort to save life

Patients with class I, II, or III status require specialty trained and experienced sedation physicians; patients with class III, IV or V status warrant consultation with anesthesiology colleagues.

High-Risk Problems

Medical conditions

ASA classes III, IV, or V

Potential airway obstruction: enlarged tonsils/adenoids, history of loud snoring, obstructive sleep apnea, foreign body aspiration or ingestion, airway abscess, oral or pharyngeal trauma, known or suspected airway masses, suspected epiglottitis

Poorly controlled asthma

Morbid obesity (>2 times ideal body weight)

Cardiovascular conditions (cyanosis, congestive heart failure, history of congenital heart disease)

History of prematurity with residual pulmonary, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or neurologic problems

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree