Fig. 41.1

Coronal (a) and Axial (b) T2 images showing a large angiosarcoma in the left temporal fossa (arrows) in a 16-year-old adolescent male

Routine spin-echo (SE) T1- and T2 weighted sequences before and after intravenous contrast administration are routine. Diffusion-weighted imaging plays a substantial role in characterizing head and neck masses. A recent study found a significant difference in apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values for malignant versus benign lesions with a 94 % sensitivity and 91 % specificity in distinguishing between the two [18].

CT can more readily identify lesions arising from the bone, and can detect bony erosion.

The role of positron emission tomography (PET) and PET-CT in childhood malignancies is continually being defined (see further, staging); it may have a distinct role in soft tissue sarcomas [19].

Biopsy

Tissue sampling can occur either via open or needle biopsy. If possible, an open biopsy under anesthesia is preferred. Closed techniques such as fine needle aspiration and tru-cut biopsy are reserved for inaccessible lesions. They obtain smaller volumes of tissue, and thus increase sampling error and inconclusive findings and often preclude molecular studies [20]. Endoscopic techniques play an important role in exploring and biopsying sinonasal and nasopharyngeal tumors. A frozen section should be obtained at the time of open biopsy to ensure that the specimen is adequate.

Lymph nodes have not been shown to be routinely involved in head and neck non-RMS. Should images or clinical exam yield concern, the patient should undergo concurrent lymph node dissection. Sarcomas with the propensity to spread to lymph nodes include synovial sarcoma, angiosarcoma, epitheliod sarcoma, and clear cell sarcoma, among others.

Pathology of head and neck sarcomas is extremely varied as this entity encompasses a large group of mesenchymal tumors of different cell origin. The most common non-RMS tumors are represented in Figs. 41.2, 41.3, 41.4 and 41.5 .

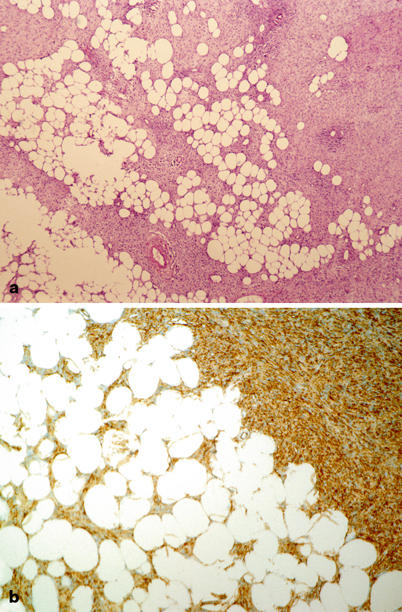

Fig. 41.2

Pathology of soft tissue sarcomas: dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. a Poorly circumscribed proliferation of spindled cells infiltrating subcutaneous tissue. The tumor profusely infiltrates lobules of adipose tissue. b Immunohistochemically, tumor cells are diffusely and strongly reactive for CD34

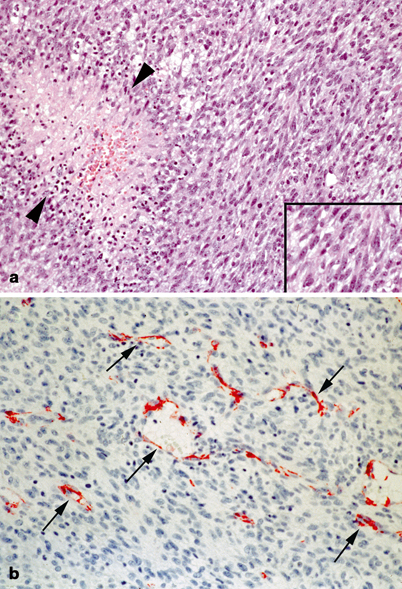

Fig. 41.3

Pathology of soft tissue sarcomas: infantile fibrosarcoma. a Cellular spindled cell tumor with numerous mitoses, apoptoses, and areas of necrosis (between arrows heads). b The tumor often exhibits numerous branching vessels imparting a hemangiopericytoma pattern (arrows). Endothelial cells are highlighted with CD31 antibody

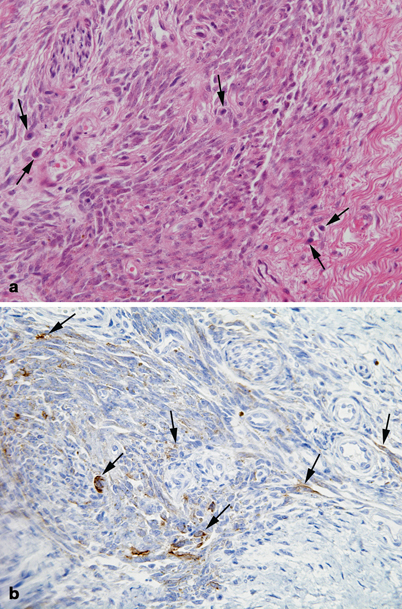

Fig. 41.4

Pathology of soft tissue sarcomas: synovial sarcoma. a Fascicles of spindled cells with variable mitotic rate and interspersed mast cells (arrows). b Tumor cells are focally immunoreactive for epithelial membrane antigen (arrows)

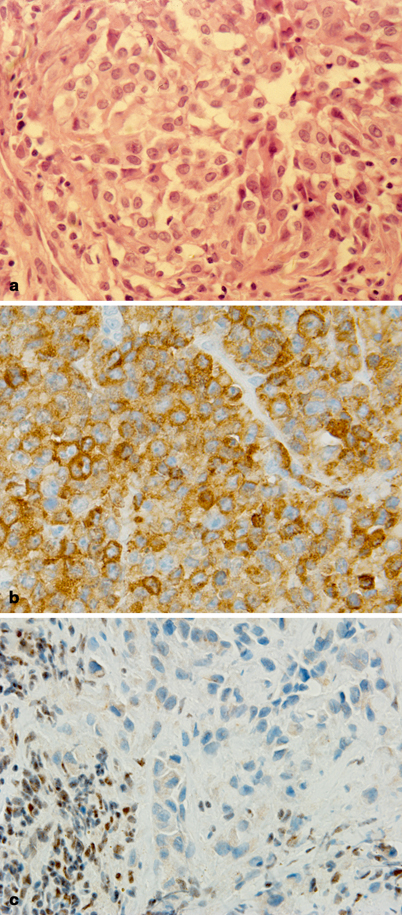

Fig. 41.5

Pathology of soft tissue sarcomas: epithelioid sarcoma. a Nests of medium to large size epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, round to ovoid nuclei with open chromatin, and single distinct nucleoli. b Tumor cells show diffuse cytoplasmic staining for Cam5.2 cytokeratin by immunohistochemistry. c Characteristic nuclear INI-1 loss is observed in tumor cells. In contrast, the lymphocytes seen on the lower left corner of the photograph show retention of nuclear INI-1

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of head and neck non-RMS includes both benign and malignant conditions (Table 41.1).

Table 41.1

Differential diagnosis for non-RMS

Oncologic | Benign |

|---|---|

1. Neuroblastoma | Hemangioma/Lymphangioma |

2. Melanoma | Ossifying fibroma |

3. Langerhans cell histiocytosis | Schwannoma |

4. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | Vascular malformation |

5. Basal cell carcinoma | Benign fibrous histiocytoma |

6. Lymphoma | Giant cell granuloma |

7. Esthesioneuroblastoma | Neurofibroma |

Osteochondroma |

Additional Workup/Staging

Laboratory Data

Complete blood count with differential, liver function tests, electrolytes.

Lumbar puncture should be performed if there is concern for bony erosion or leptomeningeal enhancement on CT or MRI.

Bilateral bone marrow aspirates and biopsies (for sarcomas known to metastasize to the intramedullary space).

Imaging Evaluation

In addition to imaging of the primary site of disease, diagnostic biopsy, and nodal assessment (as stated earlier), a metastatic work-up should be performed as follows:

CT scan of the chest: recommended to assess for pulmonary nodules. This modality is limited in many disease types by its inability to distinguish benign from malignant lesions [21].

Positron emission tomography: distant metastases and lymph node metastases have been reported to be superiorly detected by PET/CT over conventional imaging studies [19, 22]. The use of PET in pediatric patients with head and neck non-RMS is not yet routine, but will likely approach the standard of care.

Treatment

Treatment for non-RMS tumors is not as well defined as that for RMS. Regardless, treatment approach should be coordinated by a multidisciplinary pediatric oncology team comprised of medical and radiation oncologists, head and neck surgeons, plastic surgeons and neurosurgeons, in addition to a nutritionist, psychologist, and physiotherapist.

Surgery

A common approach to therapy is aggressive resection following biopsy [23]. The extent of surgical resection in RMS is clearly prognostic as shown by the IRS [24]. The extent of surgical resection and residual disease is likewise reported to be prognostic in non-RMS tumors [4, 8, 25, 26]. Nasri et al. demonstrated that tumors of the oral cavity, pharynx, and skin extent the best prognosis, likely due to their ease of surgical resection [4]. Although complete surgical resection with negative margins offers the best chance of survival, location often precludes clear margins and more aggressive surgical resection can lead to unacceptable morbidity.

Given the role of surgery, non-RMS tumors are grouped similarly to the IRS RMS schematic, reflecting the extent of surgical resection. (Table 41.2).

Table 41.2

Disease grouping dependent upon extent of surgical resection

Group I | Localized disease, completely resected |

Confined to muscle/organ of origin | |

Contiguous involvement-infiltration outside the muscle or organ of origin, as through fascial planes | |

Group II | Total gross resection with evidence of regional spread |

Microscopic residual disease | |

Regional disease with involved nodes, completely resected with no microscopic residual | |

Regional disease with involved nodes, grossly resected, but with evidence of microscopic residual and/or histologic involvement of the most distal regional node (from the primary site) in the dissection | |

Group III | Incomplete resection with gross residual disease |

After biopsy only | |

After gross major resection of the primary | |

Group IV | Distant metastatic disease present at onset |

Lung, liver, bones, bone marrow, brain, distant muscle/nodes | |

The presence of positive cytology in CSF, pleural or abdominal fluid, as well as implants on pleural or peritoneal surfaces |

Grading and Staging

Tumors are graded per the following schematic:

Grade I

Myxoid and well-differentiated liposarcoma

Deep-seated dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

Well-differentiated or infantile (≤ 4 years old) fibrosarcoma

Well-differentiated or infantile (≤ 4 years old) hemangiopericytoma

Well-differentiated malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma

Angiomatoid malignant fibrous histiocytoma

Grade II

Sarcomas not specifically included in Grade I or III and in which: less than 15 % of the surface area shows necrosis, and/or the mitotic count is less than or equal to 5 mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields (hpf) using a 40× objective.

As secondary criteria, nuclear atypia is not prominent and the tumor is not markedly cellular .

Grade III

Pleomorphic or round cell liposarcoma

Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma

Extraskeletal osteosarcoma

Malignant triton tumor

Alveolar soft part sarcoma

Angiosarcoma

Synovial sarcoma

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma

Sarcomas not specifically included in Grade I or II and in which: greater than 15 % of the surface area shows necrosis, and/or the mitotic count is greater than 5 mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields (hpf) using a 40× objective.

Marked atypia or cellularity are less predictive but may assist in placing tumors in this category.

Staging

Staging | Primary tumor | Regional LNs | Distant metastases | Histologic grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|

I | Any | N0 | M0 | G1,G2 |

II | T1a, T1b, T2a | N0 | M0 | G3 |

III | T2b | N0 | M0

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|