This presentation will cover in detail those examination procedures that are specific to the SOT protocols. Standard examination procedures are also a vital part of the initial examination and should be used in conjunction with these SOT specific procedures to get a full picture of the neurological and structural state of the pediatric patient.

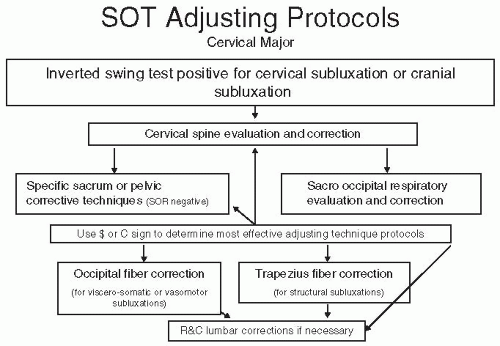

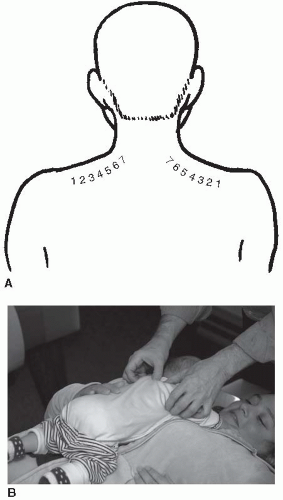

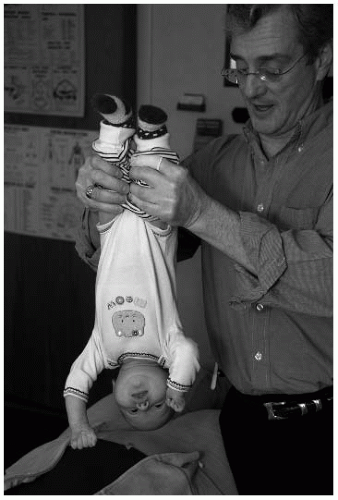

Inverted Swing Test

Grasp the infant with one hand under the occiput while the other hand holds the shins. If the infant is too large, then grasp the shins only, one in each hand. Slowly raise the infant off the table until he or she is suspended fully upside down. Gently induce a mild swinging motion. A normal child will hang relaxed and unconcerned. If the child laterally bends or rotates his or her head, it may be evidence of a cervical subluxation (

Fig. 28-1).

If the child exhibits a short leg, this suggests a category II subluxation. If the legs remain balanced but the child tenses, then a possible category I is present. Finally, if the head flexes or extends or there is significant blanching and flushing, then a cranial lesion is possible (for indicators, see “The Cranium” later in this chapter). Contraindications for this procedure include hydrocephaly, hip dysplasia, recent head trauma, and cranial shunts.

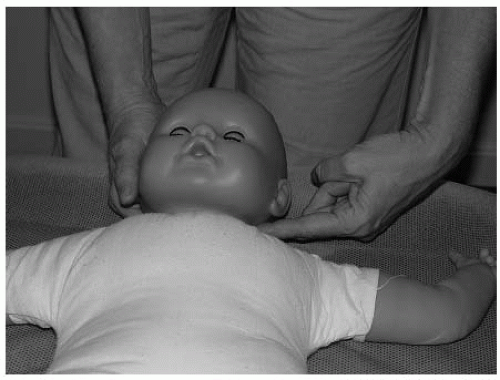

Condylar System Evaluation

Atlanto-Occipital Restriction Contacts are made bilaterally, with the fingers on the occipital bowl and the thumbs contacting the right and left frontal region (

Fig. 28-2). The clinician holds the skull lightly and bends it laterally, moving the chin to both the right and left. The side of restriction is the side of the subluxation. It is important to bend laterally the condylar system without involving the cervical spine.

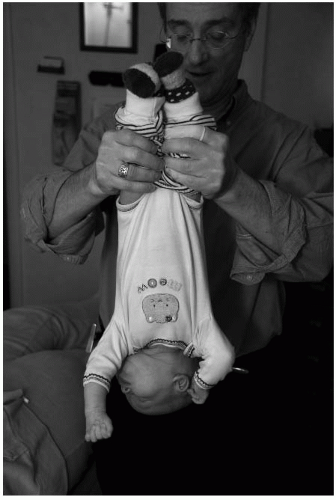

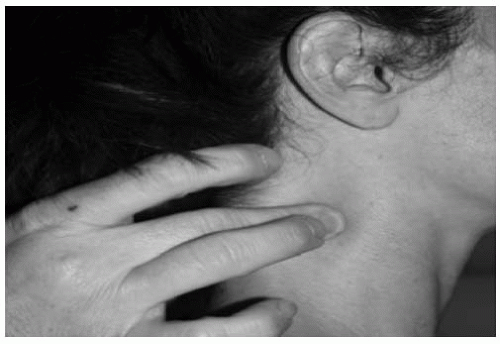

Atlas Occipital Decompression This is caused by a hyperextension trauma (usually during the birth process) and is found by extending and flexing the infant’s occiput upon the atlas (

Fig. 28-3). The clinician holds the child’s occiput with a four-finger contact while placing the thumbs anterior to the ear then gently rocks the head into extension then flexion. If there is restriction while trying to bring the head into flexion, then the occipital condyles are shifted anterior in relation to the atlas.

High Occiput The doctor can palpate the tension at the atlas occipital condyles bilaterally (

Fig. 28-4). The side with the most tension plus restricted range of motion (ROM) is the side of the high occiput, especially during side bending or lateral flexion. Visual analysis may also show a high occiput in the prone and seated positions. With the patient in the prone position, the chin will tend to deviate towards the side of the high occiput.

Cervical Spine Evaluation

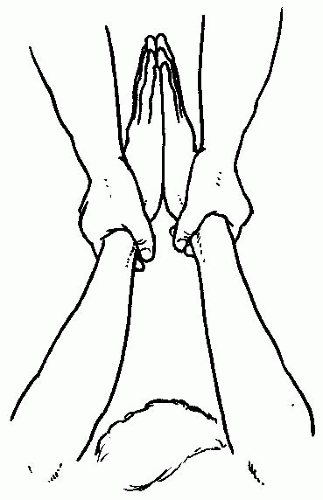

Cervical Stairstep Cervical stairstep can be performed on an infant as long as the clinician can get the child to relax, although it is easier to evaluate older children once cervical motor control has be obtained (

Fig. 28-5). The clinician places the child supine on top of the parent or adjusting table then spreads the fingers so that the index and middle fingers are in front of the ear and the ring and little fingers are behind the ear. The thumbs gently rest on the parietals approximately ¾ in. from the suture, with no pressure over the bregma. The clinician then gently compresses the head and cervical spine straight caudally, making sure the face and chin remain parallel to the ceiling and the head is not flexed or extended. As a caudal pressure is gently applied, the doctor feels four distinct steps, beginning at the cervical thoracic junction. These represent the motion of the motion segments of the cervical spine: T1-C7 (step 1), C6-C5 (step 2), C4-C3 (step 3), C2-C1 (step 4). If a step locks, the subluxation is at that level and one of fixation. If a step skips and goes past to the next step, the subluxation may be one of hypermobility at that level.

Global Neck Mobility Neck mobility is important when considering central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction or disease. Suppleness or rigidity may be determined by the clinician cradling the child’s head in his or her hands while facing the child’s head while the child is in the supine position. The clinician moves the head in all directions and notes any resistance, especially during flexion.

Sacral Motion

SI Mobility SI mobility should be equal on each side. With the child in the supine position, the doctor places the thumb of each hand on the anterior superior iliac spine and the index finger on the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) (straddling the ilium) then gently applies a rocking motion to each innominate in an anteroposterior direction, feeling for normal motion (

Fig. 28-6).

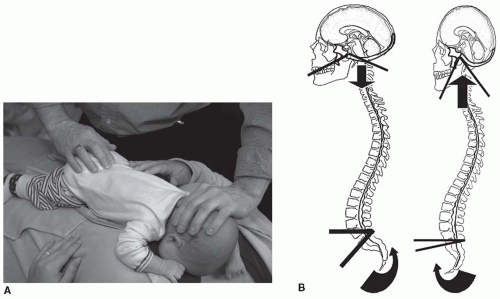

Sacro Occipital Reciprocal Motion Technique Placing one hand on the sacrum parallel to the spine and the other on the occiput perpendicular to the spine (

Fig. 28-7), the doctor feels for reciprocal motion. During inhalation the sacral base moves posterior and caudal and the occiput moves inferior and anterior into flexion. The reverse is true during exhalation/extension: the sacral apex moves posterior and caudal whereas the occiput moves posterior and superior.

The doctor can also rotate (Y axis) the occiput and sacrum in opposite directions and feel for the freedom of movement. If a restriction is present in reciprocal or rotational ranges of motion, then the clinician should also check C2 and C3 for subluxations. Correction of C2 or C3 should be done during the next visit.

SI Subluxation The doctor presses directly over the SI joint on each side of the pelvis (

Fig. 28-8). The infant crying or showing signs of discomfort suggests sacral subluxation. In this situation, when the doctor is correcting

SI subluxations, the corrective force is directed to the sacrum and its relationship to the ilium. All corrective forces will be applied directly to the sacrum. If the parent states that the child is difficult to diaper, especially if the infant struggles or will not separate his or her legs, a possible sacral dural pull subluxation may be indicated.

Palpation and Evaluation of the “Dollar Sign” A positive “dollar sign” indicator is present when the area designated as the dollar sign (where the gluteus medius, minimus, and maximus and the piriformis converge) is palpated and either a hyper- or hypotonicity is detected (

Fig. 28-9). A dollar sign refers to an area the size of a silver dollar in an adult; in a young child this size is smaller, closer to a quarter or a 2010 dollar coin. Its location is approximately 2 in. inferior to the PSIS and an inch lateral.

Pain and discomfort may be elicited on one side in relation to the other. In pediatrics the dollar sign that is the most taut or tender is considered to be major, and it is the one that should be corrected first. A major dollar sign is indicative of meningeal or dural subluxations that tend to have more of a global effect on the CNS.

The doctor uses his or her thumb or index finger to palpate the tension in each dollar sign. Mild to moderate pressure is used at the central aspect of the dollar signs in a posteroanterior direction.

Palpation and Evaluation of the Crest Sign A positive crest sign is present when there is increased tension on one side in relation to the opposing crest. It usually is indicative of a predominantly structural musculoskeletal subluxation complex that will respond well to more structurally oriented techniques or high-velocity/lowamplitude adjustments.

To locate the active or major crest sign, the thumbs gently roll off the crest of the ilium 1 in. lateral to the spinous process at the level of L4 and press gently medially toward the spine (

Fig. 28-10). Increased tissue resistance or tension in this area (where the quadratus lumborum and erector spinae intersect) is indicative of a positive crest sign in need of correction.

Specific Reflex Thoracic and Lumbar Evaluation Procedures

Trapezius Fiber Analysis The trapezius fibers are located from the acromioclavicular V to just lateral to the transverse process of T1 (

Fig. 28-11). They are numbered

one through seven; fiber 1 is at the acromioclavicular V, and fiber 7 is lateral to the transverse process of T1. The fibers are palpated with the thumbs from the lateral aspect of the transverse process of T1 (fiber 7) to the acromioclavicular V. In infants, about 2 lb of pressure at fiber 7 is used. The clinician gradually decreases the pressure as he or she palpates laterally to fiber 1. The examiner is feeling for an increased tension, nodulation, or discomfort at a specific fiber. This is considered to be an active trapezius fiber and is diagnostic of a straight inferior tippage (hyperextension) of the involved vertebrae. Once an active fiber is found, the doctor palpates the related thoracic or lumbar vertebrae spinous process to elicit either a pain response or swelling at the inferior aspect of the involved spinous process (

Table 28.1). Restriction will be felt when attempting to move the spinous in an inferior superior direction.

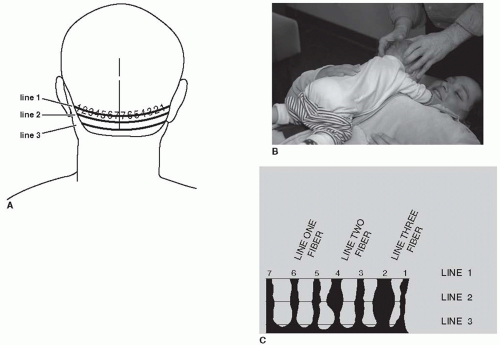

Occipital Fiber Analysis There are seven occipital fibers located from just lateral to the external occipital protuberance to the occipital mastoid V (

Fig. 28-12). The fibers are evenly spaced with fiber one starting at the occipital mastoid V and the seventh fiber just lateral to the external occipital protuberance.

There are three occipital lines, each containing seven fibers, located directly below each other from the superior nuchal line to the inferior nuchal line. For the purposes of this section, the author will be discussing lines one and two. Palpation of the fibers is done by placing the index fingers at the occipital mastoid V (fiber 1) and the middle finger directly below and slightly behind it. The middle finger then gently tractions the tissue laterally as the index finger palpates the line 1 fiber. As the clinician moves from fiber 1 to fiber 7, the index finger stays slightly in front on the middle finger as it gently tractions the tissue laterally to make the fiber more accessible.

A line 1 fiber feels like a taut, slightly swollen string and is usually painful. The line 2 fiber is a slightly swollen nodulation directly below the line 1 fiber. Once the doctor finds a line 1 fiber, he or she should palpate directly below it to determine if it has progressed to a line 2 fiber. Generally, there is not a line 2 fiber unless there is an active line 1 fiber directly above it. If only a line 1 fiber is found, then the related vertebra (see chart below for correlations) is adjusted according to line 1 protocols; however, if the fiber extends into line 2, then only line 2 adjustment protocols are to be used.

Resistance and Contraction (R&C) Factors for Lumbar Subluxation Evaluation These indicators are based on the “Lovett Brother” relationship between the cervical and lumbar vertebrae. Proprioceptors and nociceptors located in the vertebral joints create reflex neurological compensations in structural distortion patterns. This phenomenon can be monitored and used to determine structural subluxation patterns in related vertebra. Cervical indicators can give the practitioner a clue to the possible presence and position of lumbar subluxations. The R&C relationships are as follows: C1-L5, C2-L4, C3-L3, C4-L2, and C5-L1 (

Fig. 28-13). Palpation just posterior to the cervical transverse processes will detect a slightly swollen, tense nodulation that often may be painful, and further palpation of the lateral aspects of the cervical bifurcated spinous processes may also have similar active indicators. In the case of the atlas vertebra, palpation of the styloid process is the correct indicator. Active indicators at the cervical transverse process is indicative of a lumbar spinous rotation to the ipsilateral side of the related lumbar vertebra, whereas an active spinous or styloid indicator is indicative of lumbar spinous inferiority on that cervical side (

Table 28.2).

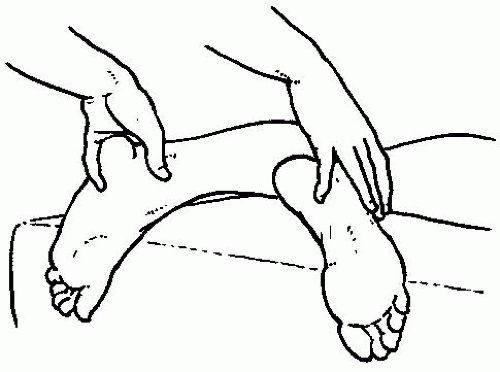

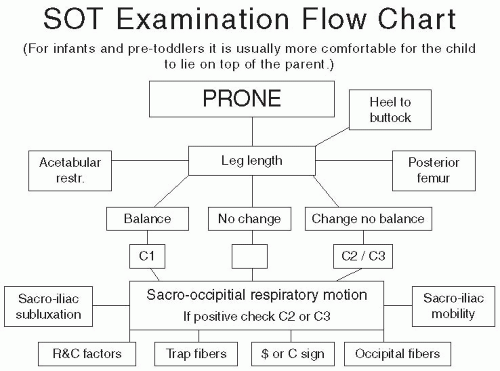

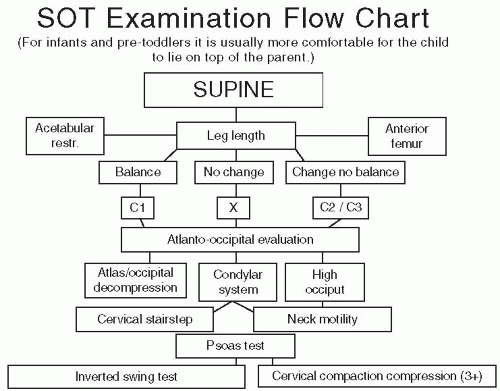

Leg Length Discrepancy The doctor should perform a leg length examination in both the prone (

Fig. 28-14) and supine positions (Charts 28-4 and 28-5). The doctor tractions the child’s legs inferior while maintaining tension on the Achilles tendons and checks for a length imbalance. Once the short leg length has been established, the parent or an assistant may gently rotate the child’s head left and right as the doctor continues to gently traction the legs inferior while looking for a change in the leg length.

1. For the child in the supine position, the doctor places his or her index finger across the Achilles tendon and the thumb across the cuneiforms.

2. For the child in the prone position, the doctor straddles the Achilles tendon with his or her thumbs and index fingers at the base of the ankle with the rest of the hand wrapped around the plantar surface of the foot.

As the child’s head is turned, the doctor maintains a steady traction while observing and feeling for a change in the leg length or Achilles tendon. If leg length changes during head turning but they do not balance, then the major cervical subluxation is most likely at C2. If the leg length balances by turning the head, then the major cervical subluxation may be C1. If there is no change in the leg length but there is a discrepancy, then the major cervical subluxation is most likely at C3 or below.

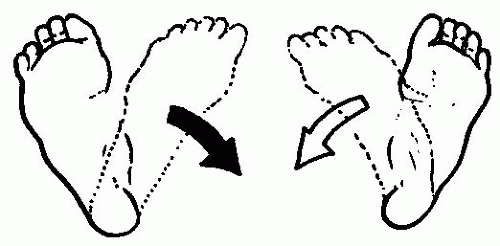

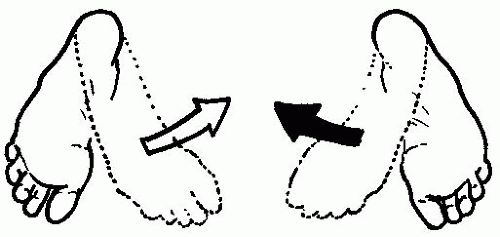

Supine Exam With the child in the supine position, the doctor checks for hip adduction, abduction, and leg balance. In this position the posture of the arms can be checked, as well as whether the posture is contracted or relaxed. For acetabular restriction, the doctor grasps the infants’ ankles and feet then rotates the feet medially while observing for limited ROM (

Fig. 28-15). The feet should medially rotate internally equally.

The psoas also can be checked in the supine position; the clinician grasps the child’s hands at the wrists, bringing the child’s arms over the his or her head and gently tractioning the arms toward the doctor. The palms are brought together and any discrepancy is noted. If there is an imbalance in this measurement, the side that appears shorter is the side of the contracted psoas (

Fig. 28-16). A positive psoas check requires correction to balance the pelvis and the diaphragmatic and pelvic transverse fascial planes.

Prone Exam With the infant in the prone position, the clinician can grasp the infant’s ankles and feet and rotate the toes medially (

Fig. 28-17). Normally, both feet should medially rotate equally. While the infant is in this position, the doctor can flex the infant’s heels toward his or her buttocks. Both heels should be able to touch the buttocks, and the side that is most restricted is the putative side of sacrum anteriority.