Oligoarticular

Onset with four or fewer joints. Most often a younger female with an asymmetric pattern and the most commonly involved joints being the knee, ankle, and elbow

Oligoarticular onset with polyarticular course

Similar to oligoarticular onset except with involvement of five or more joints 6 months after disease onset

Polyarticular-rheumatoid factor negative

Onset with five or more joints. Most often a younger female with a symmetric pattern involving the wrists and small joints of the hands

Polyarticular-rheumatoid factor positive

Onset with five or more joints. Most often a teenage female with a symmetric pattern involving the wrists and small joints of the hands

Psoriatic arthritis

Onset with either an oligo- or polyarticular asymmetric pattern. Onset most often from 9–11years of age with slight female predominance, both upper and lower extremity involvement, and a propensity for the small joints of the hands (dactylitis) – particularly the DIP joints

Enthesitis-related arthritis (formerly juvenile spondyloarthropathy)

Onset with oligoarticular arthritis in an asymmetric pattern primarily of the large joints of the lower extremities. Most often a male age 13 years or older with accompanying lower extremity enthesitis and the possible later evolution of sacroiliitis and lumbosacral spine involvement

Systemic

Onset with either a polyarticular or oligoarticular pattern with both upper and lower extremity involvement at any age with a slight male predominance. There are accompanying signs of systemic disease such as hectic high fevers, cutaneous eruption, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly

Other or undifferentiated

A subset that does not meet the criteria for one of the designated categories or meets the criteria for two categories

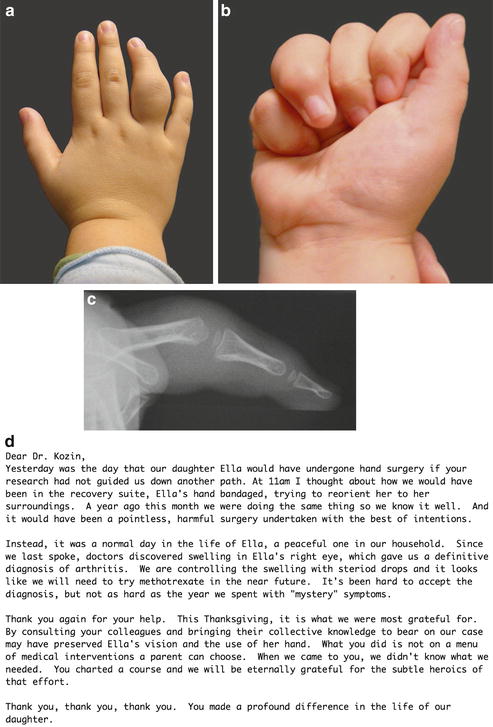

Fig. 1

Images of a 3½-year-old girl with a history of 1 year of right ring finger swelling. Rheumatologic workup was negative. Repeat synovectomy was scheduled and the patient was seen for a second opinion. The surgery was canceled and the patient was referred to pediatric rheumatologist and ultimately diagnosed with inflammatory arthritis. Photographs show right ring finger dactylitis (a) and decreased flexion (b). (c) Lateral radiograph shows fusiform soft tissue swelling and preservation of the joint structure. (d) Letter of appreciation (Courtesy of Shriners Hospital for Children, Philadelphia, PA)

At onset, most children present with morning stiffness and mild to moderate pain on motion. Shortly thereafter, the child develops recognizable joint swelling and warmth. Erythema is not usually present. Range of motion can be lost rather quickly, notably in extension about the elbow, wrist, and/or digits. Synovial cysts and small outpouching of synovium are often seen, particularly over the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints and about the wrist joint. Extensor tenosynovitis on the dorsum of the hand is common. Limb or digital growth disturbances may occur, particularly when arthritis is poorly controlled. Bone pain or tenderness is not common and should alert the clinician to the possibility of osteomyelitis or a malignancy. Night pain is particularly worrisome for the presence of a malignancy.

The most important responsibility of the surgical consultant is to make the correct diagnosis based upon the historical facts, physical examination, and radiographic changes (Fig. 2). Patients often present with a history of recent trauma. Differentiating inflammatory mediated from traumatic articular changes is critical to making the diagnosis. The young skeleton is relatively resistant to trauma with thick peripheral cartilage protecting precious ossification centers and stout ligamentous attachments that shield against ligament injuries. The most typical presentation of JIA, particularly the oligoarticular subtype, is painless restricted range of motion of the affected joint(s) along with radiographic abnormalities. Characteristic radiographic findings in children with inflammatory arthropathy include regional osteoporosis, decreased joint space, variation in bone outline as a result of erosions or bone cysts, carpal malalignment, and advanced skeletal maturity of the affected joint. Advanced skeletal maturity is the hallmark x-ray finding and secondary to the hyperemia and inflammation that results in earlier ossification compared to the unaffected side (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2

Images of a 5-year-old girl who fell on outstretched right wrist and was placed in a cast for fracture. She presented for a second opinion with surgery scheduled for presumptive diagnosis of perilunate dislocation. Photographs show limited wrist extension (a) and symmetric wrist flexion (b). AP and lateral radiographs of normal a left wrist (c). AP and lateral radiographs of a right wrist with advanced skeletal maturity show disruption of the Gilula arcs and dorsal displacement of the capitate relative to the lunate (d) (Courtesy of Shriners Hospital for Children, Philadelphia, PA)

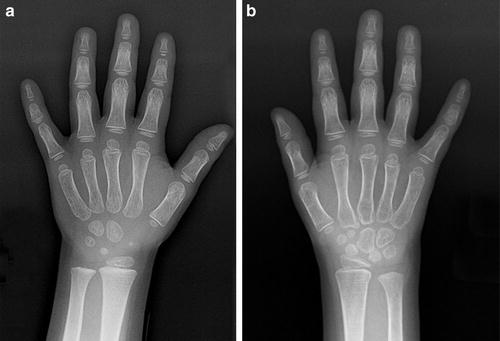

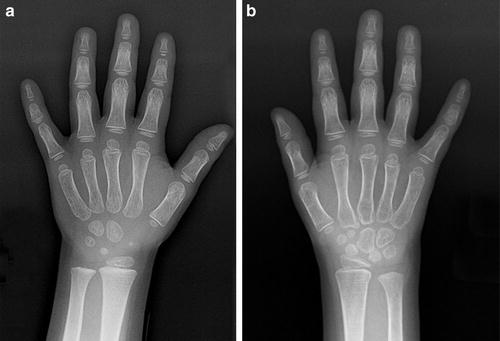

Fig. 3

PA radiographs of a 4-year-old girl with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and decreased right wrist motion. (a) View of a normal left wrist with four carpal bones ossified. (b) View of an affected right wrist with seven carpal bones ossified, consistent with advanced skeletal maturity (Courtesy of Shriners Hospital for Children, Philadelphia, PA)

In comparison to adults with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the rheumatoid factor screening test is negative in all children with oligoarticular JIA. Similarly, most young polyarticular children (younger than 11 or 12 years of age) are also rheumatoid factor negative. Therefore, the absence of this laboratory marker does not rule out the diagnosis of inflammatory arthropathy. In children with both oligoarticular and polyarticular JIA, the antinuclear antibody (ANA) is often positive. In children with the enthesitis-related arthritis subtype, the HLA B27 antigen is positive in 85–90 %. Inflammatory markers such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are slightly elevated in oligoarticular JIA but may also be normal in many children.

A history of “trauma” and negative laboratory studies may result in an unnecessary surgical procedure. When in doubt, a team approach to diagnosis and management is helpful. Blending the knowledge and perspective of a pediatric rheumatologist, pediatric orthopedist, and rehabilitation physician will facilitate appropriate diagnosis and disease-specific management. For those colleagues without such resources, do not be afraid to reach out for this expertise. The Internet and multiple Listserv interfaces have expanded the resources for consultation services; however, one must remember to remove patient identifying information when transmitting the data.

Treatment of JIA

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) | |

Nonoperative management | |

Indications | Contraindications |

All persons with active JIA | None |

Mainstay of treatment | |

Limit irreversible articular cartilage | |

Promote better outcomes | |

The management of JIA has changed considerably within the last 10–15 years, primarily as a result of the recognition that earlier treatment limits irreversible articular cartilage and promotes better outcomes. The introduction of disease-modifying drugs and biologic agents has altered the clinical and radiographic consequences of the disease. This more focused therapeutic approach requires supervision by a pediatric rheumatologist with the knowledge and experience to plan the dosage of each medication, assess the risks and benefits of pharmacological agents, and monitor the necessary parameters to assure safety and efficacy. In addition to the physician team, it is important to provide an occupational therapy program and provide social, psychological, and nutritional support.

The principles of surgical management remain unchanged. A team approach identifies those patients that would benefit from surgical intervention. The child is evaluated by the pediatric hand surgeon as well as the occupational therapist. Function always overrides form and the assessment of independence and ability to perform activities of daily living is pivotal in the decision-making process. Subtle difficulties can often be overcome utilizing occupational therapy suggestions or simple adaptive equipment (e.g., buttoning and zippering devices).

Children with chronic inflammatory arthritis , systemic lupus erythematosus, and other autoimmune disorders rarely require salvage procedures to treat arthritic changes of their wrists or elbows. Early disease recalcitrant to noninvasive management, however, requires primary surgical treatment in the form of open or arthroscopic synovectomy . Once there is noteworthy loss of articular cartilage and/or the joint architecture is irreversibly altered, the goal is to preserve the unaffected painless portion of the joint for motion or to resurface or eliminate the damaged articular surfaces. Arthroplasty is suitable for the lower extremities of children with inflammatory arthropathies, although the lifelong activity restrictions are stringent and implant longevity remains uncertain. The preservation of lower extremity joint motion is more critical for ambulation and for activities of daily living. In the upper extremity (shoulder, elbow, wrist, and hand), biological interposition arthroplasties and limited fusions are more widely accepted since the durability of upper extremity implant arthroplasty is even more dubious.

Early Medical Therapeutic Intervention

Intra-articular Corticosteroid Injections

This therapy is most commonly used for larger joints in oligoarticular JIA, but may also be done for selective joints in other subtypes when these remain active despite more advanced medical intervention (Unsal and Makay 2008). Injections also may be used as bridge management for polyarticular disease as further therapeutic agents are being introduced. Triamcinolone hexacetonide rather than triamcinolone acetonide is favored in children because of its extended therapeutic benefit at least 6 months in more than 60 % of joints treated. Early joint contractures may also respond favorably to intra-articular corticosteroids and the occurrence of limb length discrepancies is decreased. Complications are limited, most often being mild localized subcutaneous atrophy and hypopigmentation at the injection site.

Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Ongoing use of NSAIDs remains an integral part of medical therapy; however, if active arthritis persists for more than 2–3 months, it is currently recommended that additional medications be included in the regimen. NSAIDs approved for use in juvenile idiopathic arthritis include ibuprofen, naproxen, tolmetin, and celecoxib. Others such as meloxicam, nabumetone, and indomethacin are also regularly used. Serious gastrointestinal side effects in this group of medications remain rare when appropriate dosage is administered in children.

Further Medical Therapeutic Intervention

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDS)

Methotrexate was introduced for treatment of JIA approximately 20 years ago and is the foundation of treatment for many children with JIA. The recommended dose is 15 mg/m2 given orally once weekly (Ruperto et al. 2004). If there is an incomplete response, subcutaneous administration is suggested. Maximum efficacy of methotrexate is seen in patients with extended oligoarthritis, whereas there seems to be little benefit in systemic-onset JIA (also known as systemic JIA or sJIA). Methotrexate limits the rate of progression of radiographic joint damage (Ruperto et al. 2008). The total course of methotrexate is usually from 3 to 5 years depending on the capacity for initial improvement and/or the development of progressive joint disease. Side effects of methotrexate with the suggested dose are minimal, primarily being nausea. Rare hepatic abnormalities are noted with leukopenia and oral ulcerative. Concomitant folic acid is administered to help reduce nausea, limit oral ulcerations, and minimize liver-related abnormalities. Very few serious infections have occurred with the use of methotrexate for JIA.

Although not approved by the food and drug administration (FDA), leflunomide and sulfasalazine are used successfully for both oligoarticular and polyarticular JIA. These agents are considered if there is intolerance to methotrexate (Silverman et al. 2005). Gold preparations, D-penicillamine, and hydroxychloroquine are no longer used to treat JIA. Since the introduction of biologic-modifying medications, immunosuppressive drugs such as azathioprine and cyclophosphamide, previously considered for refractory JIA, are rarely needed.

Oral or Intravenous Corticosteroids

Because of their well-recognized and widespread adverse effects, all pediatric rheumatologists attempt to avoid or minimize the use of systemic corticosteroids for JIA. In certain situations, however, bridge therapy is of considerable value while other therapeutic agents (DMARDs or biologic agents) are being introduced. Corticosteroids are often needed to control the severe systemic features of systemic-onset JIA. The recent introduction of anti-interleukin-1 and anti-interleukin-6 agents for systemic-onset JIA (see below) will likely limit the need for corticosteroids in the future.

Biologic-Modifying Medical Therapeutic Intervention

Antitumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Agents

In children whose arthritis remains considerably active in spite of intra-articular corticosteroid therapy, NSAIDs and DMARDs, biologic drugs are introduced. Two anti-TNF agents, etanercept (Lovell et al. 2000; Lovell et al. 2008a), and adalimumab (Lovell et al. 2008b), are approved for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Etanercept is a genetically engineered molecule consisting of a TNF receptor fused with the Fc domain of human IgG1 which binds TNF. Adalimumab is a humanized monoclonal anti-TNF antibody with high binding activity to TNF. Etanercept is administered subcutaneously either once or twice weekly and adalimumab every other week. Etanercept was approved by the FDA in 2001 for use in children aged 3 years or above with JIA and adalimumab in 2008 for children age 4 years or above. Both etanercept and adalimumab are also FDA approved for use in adult psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree