RESPIRATORY COMPLICATIONS

Key Points

• Pregnancy does not predispose to pre-existing pulmonary disorders but may intensify the pathophysiologic alterations in lung function, thus increasing the risks of medical complications.

• Poor lung function can adversely affect not only maternal but also fetal oxygenation.

• Most routine diagnostic tests and treatment algorithms are generally considered safe during pregnancy.

• Evaluation and optimization of chronic pulmonary conditions before conception should be considered in order to improve perinatal outcomes.

Background

Physiologic Adaptations of the Respiratory System

• During pregnancy, the diaphragm rises by 4 cm, the transverse diameter of the thoracic cage increases by 2 cm, and the subcostal angles increase from 68 to 103 degrees at term.

• Increased oxygen demands of pregnancy are met by deeper ventilation rather than more frequent respiration. The minute ventilation increases 40% due to an increase in tidal volume (the amount of air inspired and expired in a normal breath) from 500 to 700 mL. The respiratory rate and the total lung capacity are unchanged (1).

• Progesterone stimulates hyperventilation, which results in a compensatory mild respiratory alkalosis with arterial pH of 7.45, and decreased PaCO2 (28 to 32 mm Hg) and bicarbonate (18 to 31 mEq/L). The normal PaO2 range is 104 to 108 mm Hg.

• Because the fetal hemoglobin has a higher O2 affinity compared to maternal hemoglobin, fetal O2 delivery is not reduced until the maternal PaO2 drops to 65 mm Hg, corresponding to a maternal O2 Sat of less than 90%.

Diagnostic Modalities

Spirometry

• Forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) are unchanged during pregnancy.

Radiologic Imaging

• The chest x-ray (two views) and chest CT are acceptable for use in pregnancy with proper shielding of the maternal abdomen as they expose the fetus to 0.02 to 0.07 mrad and less than 1 rad, respectively (2).

• Risks of fetal anomalies, growth restriction, or abortions are not increased with radiation exposure of less than 5 rad. Cumulative dosimetry should be calculated if multiple x-rays are anticipated.

• One to two rad of fetal radiation exposure may increase the risk of leukemia from the background rate of 1 in 3000 to 1 in 2000 children.

ASTHMA

Background

• Asthma affects approximately 10% of reproductive-age women in the United States (3).

• Severity is unchanged in 50%, improved in 29%, and worse in 22% (4). In general, women with poorly controlled or severe asthma are more likely to worsen during pregnancy.

Definition

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways that causes exaggerated bronchial smooth muscle contraction, mucus hypersecretion and edema, and airway wall remodeling. Bronchoconstriction results from IgE-dependent release of histamine, tryptase, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins from the mast cells. Atopy is the strongest identifiable predisposing factor.

Evaluation

History of Precipitating Factors

• Inhalant allergens: Animal allergens, house-dust mites, cockroach allergens, indoor molds, outdoor allergens

• Occupational exposures

• Irritants: Tobacco smoke, pollution, and irritants

• Others: Rhinitis/sinusitis, gastroesophageal reflux, aspirin, other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, sulfites (a common preservative for processed food), topical and systemic nonselective β-blockers, and viral respiratory infections

Physical Evaluation

• Physical findings: Poor air entry, expiratory wheezing, prolonged phase of forced exhalation, use of accessory muscles, nasal secretion, mucosal swelling, nasal polyp, and atopic dermatitis/eczema.

• Spirometry: Decreased FEV1 and FEV1/FVC measurements, as well as an increase of 12% or greater and 200 mL in FEV1 after inhaling a short-acting bronchodilator.

• Peak expiratory flow (PEF) measurements show diurnal variations of 20% or greater.

• Arterial blood gases (performed with severe exacerbation or poor response to initial treatment) show hypoxemia associated with an elevated PaCO2. This should be interpreted as a sign of severe respiratory compromise.

Treatment

Antepartum Management

• Monitor asthma with spirometry or PEF measurements.

• Monitor fetal growth with ultrasound examinations if asthma is suboptimally controlled.

• Reduce exposure to allergens.

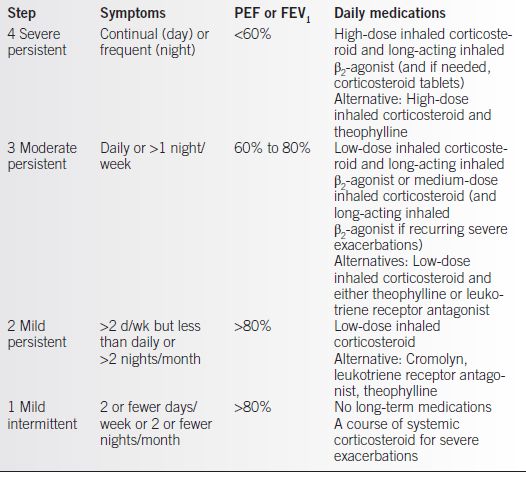

• Pharmacotherapy (Table 14-1) is managed in a stepwise approach (5).

• There is no evidence of teratogenic effects in humans from β2-agonists, theophylline, cromolyn, and inhaled corticosteroids. There is conflicting evidence suggesting an increased risk of isolated cleft lip from 0.1% in the general population to 0.3% in women using systemic steroids during the first trimester (6). There are minimal data available on the fetal effects of leukotriene modifiers.

• Theophylline levels should be monitored (serum concentration of 5 to 12 μg/mL) due to its decreased clearance in the last trimester.

• Treatment of exacerbating factors is paramount:

• Intranasal corticosteroids are the most effective medications for chronic rhinitis.

• Loratadine and cetirizine are the preferred nonsedating antihistamines.

• Influenza vaccination is recommended annually during influenza season (October to May) regardless of gestational age (7).

• Asthma is an indication for pneumococcal vaccine during pregnancy (8).

Table 14-1 Stepwise Approach to Pharmacotherapy of Asthma

From NAEPP Working Group Report on Managing Asthma During Pregnancy. Recommendations for Pharmacologic Treatment: Update 2004. NIH Publication No. 05-3279. Bethesda, MD.

Acute Exacerbation

• Obtain history, physical examination, pulse oximetry, FEV1 or PEF, arterial blood gas, and chest x-ray if pneumonia suspected.

• Administer oxygen by face mask to achieve O2 Sat greater than 95%.

• Start intravenous hydration and nebulizer treatment with:

• Albuterol 2.5 to 5.0 mg every 20 minutes for three doses, then 2.5 to 10 mg every 1 to 4 hours as needed.

• Add ipratropium if there is a severe exacerbation.

• Add systemic corticosteroids if refractory to above regimen.

• Oral “burst” of prednisone 60 to 80 mg/d for 3 to 10 days in outpatient management.

• Intravenous prednisone or methylprednisolone 120 to 180 mg/d in three or four divided doses for 48 hours, then 60 to 80 mg/d until PEF reaches 70% of predicted or personal best in inpatient management.

• Consider admission to the intensive care unit if poor response (FEV1 or PEF less than 50%, PaCO2 greater than 42 mm Hg, mental status changes) or signs of impending respiratory arrest.

• Provide continuous electronic fetal monitoring if fetal viability (≥23 weeks) is present.

Labor Management

• Continue prenatal asthma medications.

• Inhaled β-agonists do not delay the onset or slow the progress of labor.

• Both prostaglandins and ergometrine (methergine) can cause bronchospasm and therefore should be avoided if possible. Hemabate, a PGF2 α, should be avoided while local dinoprostone, a PGE2 analog, and misoprostol, a PGE1 analog, can be used safely.

Complications

• Poorly controlled asthma is associated with increased risks of preeclampsia, prematurity, and low birth weight (9).

• Pregnancy does not alter the diagnostic tests for or the treatment of asthma.

• Inadequate control of asthma can cause more harmful fetal effects than the medications.

INFLUENZA

Background

Influenza A and B are the two types of influenza that can cause epidemic human illness during the winter months (October to May). Influenza is airborne with an incubation period of 1 to 4 days. It is usually a self-limited respiratory illness lasting a few days, but women in the third trimester have an increased risk of complications.

Evaluation

• Signs and symptoms include fever, myalgia, headache, malaise, cough, sore throat, and rhinitis (10).

Treatment

• Immunoprophylaxis is associated with reductions in influenza-related respiratory illness, physician visits, hospitalization, and death.

• Inactivated influenza vaccine is preferred and may be given in any trimester (11), postpartum, and during breast-feeding. Postpartum vaccination can protect infants from influenza as children under 6 months of age cannot be vaccinated.

• No data or evidence exists of any harm caused by the low level of mercury exposure that might occur from influenza vaccination (11).

• Influenza and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines can be given concurrently.

• The intranasal live attenuated influenza vaccine, marketed as FluMist, should not be used during pregnancy.

• The influenza antiviral agent oseltamivir (FDA Category C) can be used in pregnancy when potential benefit justifies the potential fetal risk (10).

Complications

• Exacerbation of underlying medical conditions (e.g., pulmonary or cardiac disease)

• Secondary bacterial pneumonia

• Coinfection with other viral or bacterial pathogens

PERTUSSIS

Background

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree