Condition |

Imaging used |

Stridor/croup, epiglottitis |

Frontal and lateral soft tissue neck and chest radiographs show steeple sign of croup and the thumb sign of epiglottitis. |

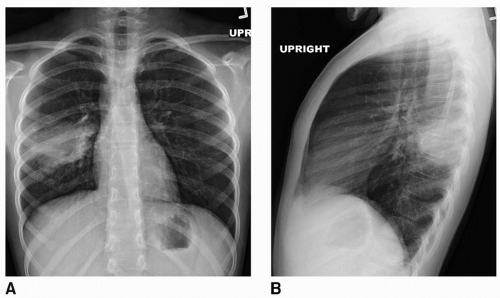

Pleural effusion |

Frontal and lateral chest radiographs may be sufficient. Decubitus radiographs may demonstrate fluid mobility. Use ultrasound if they are inconclusive or localization for drainage is required. Use computed tomography (CT) with contrast if there is concern for empyema, loculated fluid, or necrotizing pneumonia. |

Pulmonary embolism |

CT with pulmonary embolism protocol is necessary, which requires excellent intravenous (IV) access for contrast. If such CT is not available, nuclear ventilation-perfusion scan is a less specific option. |

Orbital cellulitis |

Orbital CT with IV contrast |

Abdominal trauma |

CT with IV contrast is the study of choice. |

Thoracic trauma |

CT with IV contrast is the study of choice. In patients with minor trauma, chest radiographs may be useful. |

Head trauma, epidural/subdural hematoma |

CT with and without IV contrast is used, with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) if CT is inconclusive. |

Stroke |

CT without IV contrast is used to evaluate for bleeding and edema, MRI without contrast and magnetic resonance arteriogram for suspected hemorrhagic etiology, and for patient with sickle cell disease. |

Extremity deep vein thrombosis |

Use venous ultrasound with Doppler. |

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt malfunction |

Shunt series (radiographs of skull, chest, and abdomen) to access for discontinuity is useful, with noncontrast head CT to evaluate hydrocephalus. |

Retropharyngeal abscess |

Soft tissue neck AP and lateral radiographs for initial evaluation. Typically, CT neck with IV contrast is used to further identify. |

Cervical spine trauma |

Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral cervical spine radiographs (also odontoid view in children >age 6 years) are useful. Use CT if there is still question of fracture. If there is concern for ligamentous injury, flexion and extension lateral radiographs or MRI without contrast are necessary. |

Scoliosis |

Use scoliosis survey (AP total spine radiograph), adding lateral view if significant scoliosis, lordosis, or kyphosis. |

Developmental dysplasia of the hip |

Imaging is not preferable until patient is at least age 2 wk; earlier imaging is often inconclusive because of transient ligamentous laxity as a result of maternal hormones. Ultrasound is the study of choice until age 6 months. AP radiograph of the pelvis after age 6 months |

Pyelonephritis |

Use ultrasound for evaluation of acute pyelonephritis or complications of pyelonephritis, such as perinephric abscess or pyonephrosis. Contrast CT, and MRI are excellent for this diagnosis. Consider voiding cystourethrogram for evaluation of vesicoureteral reflux once infection has resolved. |

Ovarian torsion |

Pelvic ultrasound with Doppler to show enlarged ovary, decreased vascularity, and peripheral cysts in ovary |

Testicular torsion |

Scrotal ultrasound |

Septic arthritis |

Most common in hip, knee, and ankle joints. US is useful to diagnose the effusions. Effusions can be tapped under US or fluoroscopy guidance to obtain joint fluid for cytology and culture. MRI is useful. |

Osteomyelitis |

Radiographs are often negative in early acute osteomyelitis, and MRI is preferred for diagnosis of acute osteomyelitis, which shows marrow edema, cortical breaks, subperiosteal and subcutaneous and muscle tissue abscesses, fistulae, and sequestrum. |

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis |

Adolescent boys and girls. AP and frog leg radiographs show extent and severity of slip, which is medial and posterior. |

Child abuse |

Complete skeletal survey may show multiple fractures in various stages of healing, metaphyseal corner fractures, posterior rib fractures, sternal, complex skull, and phalangeal fractures, all of which are highly suggestive of child abuse. CT or MRI of the head is useful to assess intracranial hemorrhage and skull fractures. |

Vascular and lymphatic malformations |

US, CT, and MRI are useful to know the type of vascular and lymphatic malformation, extent of the lesion, and vascularity. |

Skeletal dysplasias |

Skeletal survey will help establish the diagnosis. |

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) |

Can affect single or multiple bones. Most common locations are skull, pelvis, femur, ribs, and humerus. On radiographs show lytic lesions with or without sclerotic rim. In the skull, lytic lesions have beveled edges. Floating tooth appearance may be seen. Vertebra plana or vertebral body compression deformity can be seen in the spine. |

Cystic neck lesions |

Thyroglossal duct cyst, dermoid, lymphatic malformation, and abscesses are the most common cystic lesions in the neck. US is preferred for initial evaluation of these cystic lesions. |