Radical Abdominal Hysterectomy

Robert E. Bristow

INTRODUCTION

Radical hysterectomy is distinguished from simple extrafascial hysterectomy by the dissection of the ureters from within the parametria and a wider resection of additional tissue surrounding the cervix, usually for an early-stage cancer of the cervix. The first radical abdominal hysterectomy for cervical cancer was performed in 1895 by John G. Clark at the Johns Hopkins Hospital under the direction of Howard A. Kelly. The vaginal approach to radical hysterectomy was described by Schauta in 1902. Ernst Wertheim contributed modifications to the procedure, and his published experience contributed greatly to the acceptance of radical hysterectomy as a viable treatment for women with early-stage cervical cancer. Later modifications were introduced by Okabayashi. Although recent attention has been directed toward implementation of a more anatomically distinct classification system of radical hysterectomy, including nerve-sparing variants, the Piver-Rutledge classification system, introduced in 1974, is still commonly referenced. In practice, there are three basic variations of radical hysterectomy. The Wertheim hysterectomy is the most commonly performed variant in the United States, has the broadest applicability, and is described in the following section. The two most common variations are the modified radical hysterectomy and the extended radical hysterectomy.

The most common indication for radical hysterectomy is the surgical treatment of early-stage (Stages IA2-IIA) cervical cancer. The efficacy of combined irradiation and low-dose chemotherapy for Stage IB2 disease has made this an uncommon indication for radical surgical treatment. Some centers also perform radical hysterectomy for Stage IIB cancer of the cervix, although this is rare in the United States. Radical hysterectomy may be indicated as completion surgery for patients with locally advanced cervical cancer with centrally persistent disease following definitive combined irradiation and low-dose chemotherapy. Radical hysterectomy is also a treatment option for patients with endometrial cancer extending to the cervix (clinical Stage II disease) and may be required as part of a larger cytoreductive surgical effort for patients with advanced ovarian cancer. The surgical principles of radical hysterectomy are also applicable to the operative management of a number of noncancerous gynecologic conditions including extensive endometriosis and uterine leiomyomata involving the cervix or lower uterine segment. Radical hysterectomy can be performed with or without pelvic lymphadenectomy or adnexectomy.

The typical route of approach to radical hysterectomy is abdominal, laparoscopic, or robotically assisted. Radical vaginal hysterectomy is uncommonly performed in the United States. This chapter addressed the abdominal approach, although the same basic principles apply whichever route is selected and are also applicable to conservative surgical approaches to early-stage cervical cancer for fertility preservation (radical trachelectomy).

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

In preparation for radical hysterectomy, all patients should undergo a comprehensive history and physical examination focusing on those areas that may indicate a reduced capacity to tolerate major surgery or disease-related characteristics (e.g., parametrial extension) that would contraindicate successful surgical resection. Routine laboratory testing should include a complete blood count, serum electrolytes, age-appropriate health screening studies, and electrocardiogram for women aged 50 years and older. Preoperative imaging of the pelvis and abdomen (computed tomography) is usually indicated to evaluate the extent of cervical pathology and associated extent of adenopathy for surgical planning purposes.

Preoperative mechanical bowel preparation (oral polyethylene glycol solution or sodium phosphate solution with or without bisacodyl) may facilitate pelvic exposure by making the small bowel and colon easier to manipulate but is not required. Prophylactic antibiotics (Cephazolin 1, Cefotetan 1 to 2 g, or Clindamycin 800 mg) should be administered 30 minutes prior to incision, and thromboembolic prophylaxis (e.g., pneumatic compression devices and subcutaneous heparin) should be initiated prior to surgery. The instrumentation will necessarily vary according to the approach selected. For abdominal hysterectomy, a self-retaining retractor (e.g., Bookwalter, Codman Division, Johnson & Johnson, Piscataway, NJ) with a fixed arm attaching the retractor ring to the operating table is advisable to optimize exposure, maximize patient safety, and reduce surgeon fatigue. A variety of instruments, in addition to the standard surgical armamentarium, can be used at the surgeon’s discretion to facilitate the retroperitoneal dissection including vessel-sealing devices, the argon beam coagulator, and surgical stapling devices. Following is a brief description of the surgical procedure used (see also video: Radical Abdominal Hysterectomy).

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Either general or regional anesthesia is acceptable. The patient should be positioned in low dorsal lithotomy position using Allen-type stirrups. The abdomen is prepped and a Foley catheter placed. Examination under anesthesia should pay particular attention to the size and topography of the cervix, uterus, proximal vagina, parametria, and uterosacral ligaments.

Either general or regional anesthesia is acceptable. The patient should be positioned in low dorsal lithotomy position using Allen-type stirrups. The abdomen is prepped and a Foley catheter placed. Examination under anesthesia should pay particular attention to the size and topography of the cervix, uterus, proximal vagina, parametria, and uterosacral ligaments.Either a low-transverse incision (Pfannenstiel, Maylard, Cherney) or low vertical midline incision will provide satisfactory exposure for radical hysterectomy, depending on patient body habitus. After abdominal entry and placement of a self-retaining retractor, adhesions are taken down, normal anatomy is restored, and the bowel is packed out of the surgical field.

The uterus is elevated out of the pelvis and manipulated by two large Kelly clamps placed across the broad ligament adjacent to the uterine fundus encompassing the round ligament, fallopian tube, and utero-ovarian ligament on each side. The broad ligament is incised cephalad to the round ligament, and the peritoneal incision extended above the pelvic brim parallel to the infundibulopelvic ligament. The common iliac artery is identified and traced distally to its bifurcation into the external iliac artery and internal iliac (hypogastric) artery, which courses deep along the lateral pelvic wall. The uterine arteries originate from the hypogastric artery within the cardinal ligament. The round ligament is identified and a ligature of 1-0 delayed absorbable suture placed as far laterally toward the pelvic sidewall as possible and held long for traction. A large hemo-clip (or suture ligature) is placed medially (uterine side) to control back-bleeding, and the round ligament is divided. An incision is created in the anterior leaf of the broad ligament and is continued medially across the vesicouterine peritoneal reflection (or fold) at the junction of the lower uterine segment and cervix.

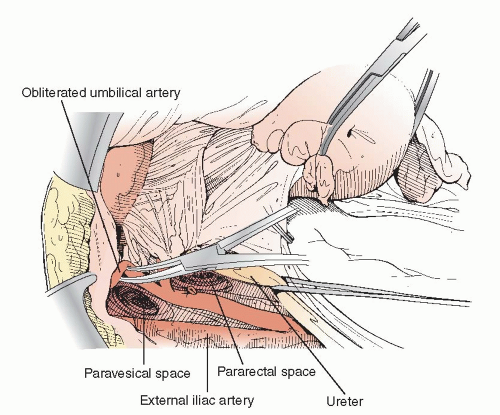

To perform radical hysterectomy safely and efficiently, six of the eight potential pelvic spaces should be developed early in the operation—the paired paravesical spaces, the paired pararectal spaces, the vesicovaginal space, and the rectovaginal space. The pararectal space is developed by carefully dissecting, with a finger or large Kelly clamp, between the hypogastric artery (laterally) and the medial leaf of the broad ligament peritoneum. The ureter is attached to the medial leaf of the broad ligament peritoneum and is most easily located at the pelvic brim in the region of the bifurcation of the common iliac artery. The ureter should be dissected from its adventitial sheath using a right angle clamp and placed within a vessel-loop for traction. The paravesical space is identified by placing upward traction on the round ligament ligature and the lateral surface of the bladder with a Babcock clamp. The obliterated umbilical artery will appear as a thick band of tissue running just lateral to the bladder, and it demarcates the medial border of the paravesical space. The paravesical space is developed with a finger or long Kelly clamp starting along the pelvic sidewall anterior to the cardinal ligament and dissecting anteriorly,

medially, and inferiorly. Both the pararectal and paravesical spaces are developed down to the level of the pelvic floor (Figure 10.1).

medially, and inferiorly. Both the pararectal and paravesical spaces are developed down to the level of the pelvic floor (Figure 10.1).

Depending on clinical indications, adnexectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy can be performed in conjunction with radical hysterectomy. These techniques are described in Chapters 2 and 12, respectively. If the adnexa are to be preserved, they are detached from the uterus and tucked into the upper abdomen. Otherwise, the infundibulopelvic ligaments are clamped, divided, secured with 1-0 delayed absorbable sutures, and the adnexa are tied to the Kelly clamps holding the uterus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree