Pulmonary

Peter P. Moschovis

Lael M. Yonker

Elizabeth C. Parsons

Benjamin A. Nelson

Efraim Sadot

Christina V. Scirica

Kenan Haver

Natan Noviski

Pulmonary Function Tests

dImages: http://www.morgansci.com/customer-resource-center/pulmonary-info-for-patients/what-is-a-pft-test-2.php

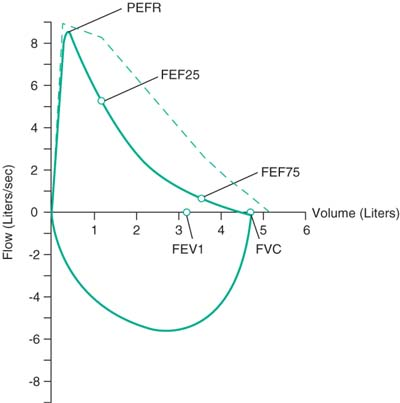

Abbreviations

FVC: Max volume expired during forced expiratory maneuver

FEV1: Volume expired in 1st sec after max inspiration

FEV1/FVC: Measure of airflow obstruction

FEF25–75: Mid flow-rate of FVC (reflects small airways obstruction, less effort-dependent, but highly variable)

DLCO: Diffusion capacity of CO

PEFR: Peak expiratory flow rate

|

|

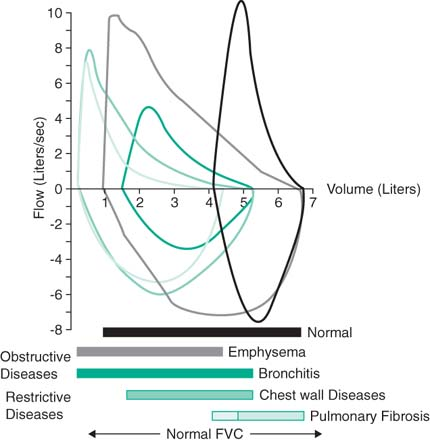

Obstructive lung disease: Asthma, protracted bronchitis, early cystic fibrosis

Restrictive lung disease: Thoracic (ILD, pneumothorax, edema, consolidation, fibrosis) and extrathoracic (obesity, resp muscle weakness, thoracic deformities, pleural disease)

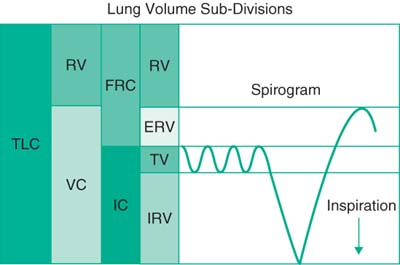

Basic Spirometry with Lung Volumes

Indications: Eval (1) if dysfxn, if obstructive, restrictive, or mixed & location & degree, (2) progression of known dz, (3) resp to bronchodilators

Relative contraindications: Hemoptysis of unknown origin, PTX, recent eye surgery (increased IOP during forced exp maneuvers)

| Parameter | Normal | Obstructive | Restrictive |

|---|---|---|---|

| FVC | ≥80% pred or LLN (Lower Limit Nml) | ↔↓ bronchodilator responsive: ↑12% or 0.2L | ↓↓ |

| FEV1 | ≥80% pred or LLN | ↓↓ bronchodilator responsive: ↑12% or 0.2L | ↔↓ |

| FEV1/FVC | 85% for 8–19 yo | ↓↓ | ↔↓ |

| RV | ↑ ↑ | ↓↓ (early) | |

| TLC | ↑ ↑ | ↓↓ (late) | |

| RV/TLC | ↑ ↑ | ↓↓ |

|

Diffusion Capacity

Indications: Eval for parenchymal dz (DLCO measures “efficiency” of gas exchange)

DLCO dependent on TLC and Hgb; any process that ↓ them will ↓ DLCO as well

↓ DLCO can be 2/2: Parenchymal or pulm vascular dz, extrapulm restriction (lung resection, scoliosis), anemia (adjust for Hgb mathematically), tachycardia

Bronchial Provocation Testing

Indication: Suspect asthma, but spirometry normal

Procedure: Spirometry before/after progressive doses methacholine, histamine, exercise, mannitol, or hyperventilation/cold air

Positive test: FEV1 reduced 20% after challenge

Respiratory Muscle Strength

Indication: Rule out muscle weakness as a cause for respiratory insufficiency

Procedure: Pt breathes against shutter valve, measure max inspiratory pressure (MIP) and max expiratory pressure (MEP); perform at least 10× for consistency

Implications: Compare to age norms, MEP <50 cm H2O suggests insuff cough to clear secretions; MIP <-80 and MEP >+80 cm H2O r/o signif weakness (adults) Thorax 1984;39:535–538

Common Respiratory Complaints

Wheezing

Acute: Asthma, bronchiolitis, anaphylaxis, toxic inhalation, medication induced (β-blocker, ASA, indomethacin), aspiration

Chronic: Asthma, GERD, protracted bronchitis, asthma, CHF, vascular rings, tracheomalacia

Workup: Consider CXR if suspect asthma or aspiration, PFTs, pH probe, fluoroscopy for tracheomalacia or foreign body

Stridor

Inspiratory: Most common, extrathoracic origin

Laryngeal (most common): Laryngomalacia (most common chronic cause), croup (most common acute cause), laryngeal web/cyst, epiglottitis, vocal cord paralysis, subglottic stenosis (postintubation or congenital), foreign body, tumor (subglottic hemangioma or laryngeal papilloma), angioedema, traumatic intubation, laryngospasm (hypocalcemic tetany), psychogenic

Nasopharyngeal: Choanal atresia, lingual thyroid or thyroglossal cyst, macroglossia or micrognathia, hypertrophic tonsils/adenoids (h/o snoring), RP or peritonsillar abscess (drooling, “tripod”-ing)

Tracheal: Tracheomalacia, bacterial tracheitis, external compression (cystic hygroma), TEF (worsens w/feeds)

Expiratory: Less common, intrathoracic; mimics asthma, but tracheal/bronchial

Tracheomalacia, bronchomalacia, vascular rings, extrinsic compression, psych

Diagnostic clues:

Worse asleep → pharyngeal (tonsils, adenoids) origin

Worse awake/with agitation → laryngeal, tracheal or bronchial origin

Worse supine → laryngo/tracheomalacia, micrognathia, macroglossia

Acute: Infxn or foreign body; psychogenic (often w/o distress, neck flexed)

Workup: AP/lateral neck films to assess upper airway anatomy, chest film if suspect foreign body aspiration, direct bronch for persistent sx or foreign body, CT to r/o extrinsic compression, barium swallow to r/o vascular compression or GERD

Treatment: See ED section for acute treatment; treat underlying cause

Cough

Acute: URI, PNA, pneumonia, aspiration, PE

Chronic: Postnasal drip, GERD, bronchitis, TB, bronchiectasis, cough-variant asthma, toxic exposure (cigarette smoke), CHF, drug (ACE-I), ILD, BOOP

Workup: ENT exam for s/sx allergic rhinitis, CXR +/- sputum if suspect infection, CT scan if suspect BOOP or chronic ILD, empiric antacid if hx c/w GERD.

Laryngomalacia

Definition

(Pediatr Rev 2006;27:e33)

Floppy tissue above vocal cords that falls into airway w/ inspiration

Collapse of supraglottic structures (arytenoids cartilages and epiglottis) w/ inspiration

Epidemiology

Most common cause of stridor in infants (∼65%–75% of all cases)

Clinical Manifestations

Begins during first 2 mo of life; infant usually happy/thriving

Noises are inspiratory and may sound like nasal congestion

Exacerbated with crying, agitation, or during an upper respiratory infection

Prone position may diminish the stridor

Diagnostic Studies

History/physical, flexible laryngoscopy, and/or bronchoscopy

Prognosis

Self-limited condition, usually resolves w/o Rx by 12–18 mo of age

In 10% of affected pts, upper airway obstruct severe enough to cause apnea or FTT

When to Refer

FTT, feeding difficulty, respiratory distress/apnea/hoarseness, cyanosis, atypical clinical course/persistent stridor

Interventions

Surgery: Supraglottoplasty

Croup

Definition

Clinical dx for acute onset of barky cough, stridor, and respiratory distress.

Epidemiology

(N Engl J Med 2008;358:4:384)

Affects children btw 6 mo–3yr old. Incidence in boys is 1.5×’s > girls.

Seasonal: Peak Sept-Dec, biennial. 5% of 2 yo will develop croup.

Clinical Course

(Lancet 2008;371:329; N Engl J Med 2008;358:4:384)

Typically 12–48 hr of preceding URI sx’s, followed by acute barky cough, hoarse voice, and respiratory distress, which are worse at night. +/- fever, mild pharyngitis. 60% children have resolution of symptoms in 48 hr.

Microbiology

Parainfluenza 1, 3, influenza A, B, adenovirus, RSV, metapneumovirus

Diphtherial and measles rare causes in nonvaccinated children (Lancet 2008;371:329)

Pathophysiology

Subglottic edema and airway narrowing.

Differential Diagnosis

(Lancet 2008;371:329)

Epiglottitis: Dysphagia, anxiety, sniffing position, toxic appearing

Bacterial tracheitis: 2–7 d prodrome, febrile, toxic, do not respond to epi nebs

Foreign body aspiration: Sudden, no fever

Retropharyngeal/peritonsillar abscess: Dysphagia, drooling, neck stiffness, unilateral cervical lymphadenopathy

Angioneurotic edema: Urticarial rash

Allergic reaction: Urticarial rash, history of allergy

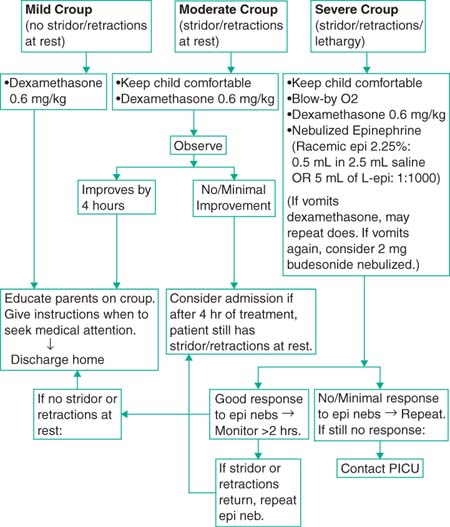

Treatment

(Lancet 2008;371:329; N Engl J Med 2008;358:4:384)

Keep child comfortable, leave in parent’s arms. Blow-by oxygen, often held by parent

Corticosteroids: Dexamethasone 0.6 mg/kg PO/IM ×1; duration of effect: 2–4 d

Racemic epinephrine: 0.5 mL of 2.25% racemic epi, or 5 mL of L-epi 1/1000

Improves symptoms within 10–30 min. Effect lasts 1–2 hr.

Heliox: For severe resp distress. Lower density helium, mixed w/ O2, ↓ turbulent flow through narrow airways. As good as, but more expensive than racemic epi.

No evidence that humidified air improves symptoms of croup. Antibiotics, antitussives, decongestants, or β2-agonists do not have a role in the Rx of croup.

Monitored at least 2–4 hr after racemic epi Rx before d/c, ensure no recurrence

Observation for 3–10 hr in ER following Rx reduces admission rate for croup.

|

Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome

(Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:775; Pediatrics 2002;109:704)

Definition

Breathing disorder during sleep w/ prolonged partial upper airway obstruct and/or intermittent complete obstruct (obstructive apnea); disrupts ventilation and sleep.

Needs to be distinguished from 1° snoring (PS), defined as snoring w/o obstructive apnea, frequent arousals from sleep, or gas exchange abnormalities.

Clinical Manifestations

Chronic snoring, daytime fatigue/sleepiness, sleep walking/talking, enuresis, periodic limb movement, headaches

Mouth breathing, nasal obstruct w/ wakefulness, adenoidal facies, hyponasal speech.

Neurocognitive deficits: Poor learning, behavioral problems, ADHD

Risk Factors

Adenotonsillar hypertrophy, obesity, craniofacial anomalies, neuromuscular d/o

Diagnosis

Pneumogram: Distinguishes between central and obstructive apnea

Polysomnography (PSG): Can distinguish PS from OSAS

Quantitative, noninvasive eval of frequency/severity of sleep disordered breathing

Confirm presence and severity of airflow obstruction; documents efficacy of Rx

Help determine the risk of postoperative complications

Determine the optimal level of CPAP when adenotonsillectomy is not an option

Studies have not determined which polysomnographic criteria predict morbidity

Treatment

Adenotonsillectomy: The most common treatment for children with OSAS

Resolution occurs in 75% to 100% after adenotonsillectomy

CPAP: Used indefinitely

For patients with specific surgical contraindications, minimal adenotonsillar tissue or persistent OSAS after adenotonsillectomy

Must be titrated in sleep lab before prescribing and needs periodic readjustment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree