Prophylactic Antibiotics for Obstetric Procedures

Infection is the most common complication associated with obstetric surgery. Accordingly, obstetricians are interested in assessing methods to reduce the likelihood of infection following selected surgical procedures. Most of the effort in clinical research has been devoted to developing and refining protocols for the administration of prophylactic antibiotics.

The first portion of this chapter reviews the pathophysiology of postoperative pelvic infections, criteria for use of prophylactic antibiotics, and mechanism of action and objectives of antibiotic administration. The second portion summarizes the results of clinical trials of antibiotic prophylaxis for cesarean delivery, pregnancy termination, cervical cerclage, and repair of episiotomy disruptions. It also considers the role of prophylaxis in patients who have meconium-stained amniotic fluid and who have vaginal colonization with group B streptococci.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF POSTOPERATIVE INFECTIONS

Multiple microorganisms that are part of the normal vaginal flora usually cause postoperative infections. The principal aerobic pathogens are group B and group D streptococci and gram-negative bacilli such as E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus species. The most common anaerobic organisms are Peptococcus and Peptostreptococcus species, Gardnerella vaginalis, Bacteroides species, and Prevotella species. Although they are of great importance in the pathogenesis of pelvic inflammatory disease, Neisseria gonor-rhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis do not typically cause immediate postoperative infections. Nor have the genital mycoplasmas been clearly established as major pathogens in patients with postoperative infections. When postoperative infections are complicated by bacteremia, the most common isolates are group B streptococci, aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobes (Duff, 1986).

The multiple aerobic and anaerobic organisms of the vagina are very well adapted for causing serious infections when they are inoculated into the upper genital tract coincident with labor, vaginal examination, or surgery. Most of the bacteria have specialized fimbriae, which enable them to adhere tightly to the columnar epithelium of the genital tract. Many of the organisms, such as group B streptococci, Bacteroides species, and the aerobic gram-negative bacilli, have capsules or specialized cell walls that impair phagocytosis by host white blood cells. Most bacteria produce a variety of proteolytic enzymes that facilitate infection of host cells. Still others have the capacity to produce enzymes that degrade many of the β-lactam antibiotics used to treat infections.

In women having cesarean delivery, the most important risk factors for postoperative infection are low socioeconomic status, extended duration of labor and ruptured membranes, multiple vaginal examinations, and preexisting lower genital tract infection (Hawrylyshyn and associates, 1981). In women having pregnancy termination, the principal risk factor is the presence of preexisting genital tract infection such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, and bacterial vaginosis. For women undergoing cerclage, the degree of cervical dilatation, the extent of membrane prolapse, and the presence of preexisting infection are key determinants of postoperative morbidity. Each of these risk factors increases the probability that a large number of potentially virulent microorganisms will be inoculated into the upper genital tract during the course of labor and/or surgery.

CRITERIA FOR USE OF ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS

The duration of therapy and the selection of specific drugs distinguish prophylactic administration of antibiotics from therapeutic administration. To be considered prophylaxis, antibiotic use should be confined to the first 24 hours in the perioperative period. In addition, as a general rule, the drugs selected for prophylaxis should have these characteristics: they should (a) be relatively inexpensive and easy to administer; (b) have fairly broad coverage against most, but not necessarily all, of the bacteria likely to be encountered in the operative site; and (c) be drugs that are not ordinarily used for treatment of an established infection (Ledger and colleagues, 1975).

Three clinical criteria should be fulfilled to justify the use of prophylactic antibiotics. First, the surgical procedure must be performed through a contaminated operative field. Second, in the absence of prophylaxis, the incidence of postoperative infection should be unacceptably high, usually above 15–20 percent. Third, patients who develop primary infections of the operative site should be at risk for potentially serious complications such as abdominal or pelvic abscess, septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis, or septic shock (Duff, 1987).

MECHANISM OF ACTION OF PROPHYLACTIC ANTIBIOTICS

Prophylactic antibiotics exert their effect in several ways. By destroying some bacteria and slowing the growth of others, they reduce the size of the bacterial inoculum present at the surgical site. Antibiotics alter the characteristics of the serosanguineous fluid that collects in or near the operative site and make this medium less suitable to support the growth of pathogenic microorganisms. When administered in prophylactic doses, antibiotics also interfere with production of bacterial proteases and impair the attachment of bacteria to the mucosal surfaces of the genital tract. Finally, when absorbed and concentrated within white blood cells, antibiotics enhance the host’s endogenous phagocytic capacity (Duff, 1987; Kaiser, 1986).

The landmark studies of Burke (1961, 1973) demonstrated that the timing of antibiotic delivery to injured tissue is of critical importance in determining the overall effect of prophylaxis. The optimal therapeutic effect occurs when antibiotics are administered to the patient just before, or coincident with, the start of surgery, when maximal bacterial contamination and tissue trauma occur.

GENERAL OBJECTIVES OF PROPHYLAXIS

The first general objective of prophylaxis is to reduce the frequency of infection of the operative site, that is, endometritis after cesarean delivery or abortion, chorioamnionitis after cerclage, and deep perineal infection after repair of a disrupted episiotomy. When patients have meconium-stained amniotic fluid, the goal of prophylaxis is to reduce the frequency of chorioamnionitis and puerperal endometritis. The objectives of prophylaxis for group B streptococcal infection are to reduce the frequency of maternal chorioamnionitis and endometritis and neonatal septicemia and pneumonia. A second general objective is to reduce the frequency of abdominal wound infection after procedures such as cesarean delivery. Wound infections are even more likely than endometritis to cause serious morbidity and thereby increase the duration and expense of hospitalization. The third general objective of prophylaxis is to reduce the risk of the rare, life-threatening complications of operative site infection such as pelvic abscess, septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis, and septic shock (Duff, 1987).

RESULTS OF CLINICAL TRIALS OF PROPHYLAXIS

CESAREAN DELIVERY

To date, more than 25 prospective, randomized, placebocontrolled trials of systemic prophylaxis for cesarean delivery have been published. The results of these investigations have been consistently impressive and are summarized here.

Essentially without exception, all studies have shown that prophylaxis decreases the frequency of endometritis in women having unscheduled cesarean after an extended duration of labor and ruptured membranes. In most investigations, the rate of postcesarean endometritis has been reduced by 50–60 percent (Duff 1987; Cartwright and colleagues, 1984).

The benefit of prophylaxis is less dramatic in women having scheduled cesarean delivery. In patient populations in which the baseline incidence of infection approaches 10 percent after even low-risk procedures, prophylaxis usually will be cost effective (Duff and coworkers, 1982b). If the baseline risk of infection is less than 5 percent, prophylaxis probably should be withheld, and antibiotic administration should be limited to patients who have evidence of overt infection.

The drugs most frequently used for prophylaxis have been the cephalosporins. Although the newer, extended spectrum cephalosporins have also been used for prophylaxis, there is no convincing evidence that these agents are superior to a first-generation drug such as cefazolin. In fact, the broader spectrum cephalosporins are considerably more expensive, and their injudicious use for prophylaxis may ultimately limit their usefulness as single agents for the treatment of an established infection (Duff, 1987; Carlson and Duff, 1990; Stiver and associates, 1983; Duff and colleagues, 1987).

Most investigators have used three doses of antibiotics for prophylaxis. However, several reports demonstrate that a single dose of drug is comparable in efficacy to multidose regimens and offers distinct cost savings (Gonik, 1985; McGregor, 1986; Padilla, 1983, and their colleagues). Accordingly, multiple doses appear to be warranted only if surgery is unduly prolonged or the patient is at exceptionally high risk of infection (Duff, 1987).

Several investigators have tried to determine whether selected patients benefit from “extended early treatment” rather than simple prophylaxis. Their efforts have been based on the premise that some high-risk patients may be so heavily colonized with bacteria at the time of cesarean that they approach a 100 percent probability of becoming infected despite prophylaxis. Unfortunately, there are no laboratory or clinical criteria that are sufficiently reliable for identifying patients as prophylaxis “successes” versus prophylaxis “failures” (Elliott and associates, 1982; D’Angelo and Sokol, 1980). Accordingly, until a simple test with high sensitivity and predictive value is available, extended prophylactic or early treatment regimens cannot be recommended.

For most operative procedures, antibiotic prophylaxis should be administered immediately prior to surgery. However, in women having cesarean delivery, delay in administration of drug until after the umbilical cord is clamped does not compromise the efficacy of prophylaxis and avoids exposure of the fetus to antibiotics prior to delivery (Duff, 1987; Gordon and associates, 1979).

In the majority of investigations, antibiotic prophylaxis has not significantly reduced the frequency of postoperative wound and urinary tract infections. Investigators who have been able to document beneficial effects have usually been caring for patients with a relatively high baseline frequency of infection.

Several investigators have studied the effect of topical antibiotics as prophylaxis against postcesarean infection. In general, topical antibiotics have been administered by irrigating the lower uterine segment, uterine incision, peritoneal cavity, and abdominal wound at appropriate intervals during surgery. Irrigation exerts its primary effect by providing a high concentration of antibiotic directly to the site of injured tissue. Systemic absorption of the antibiotic occurs, however, especially when both intrauterine and intraperitoneal irrigation is performed (Duff and colleagues, 1982a).

Unlike systemic prophylaxis, not all antibiotics have been equally effective when administered by irrigation. Observed differences in treatment effect appear to be due to differences in irrigation technique and pharmacokinetic properties of individual antibiotics. Moreover, although irrigation is effective, it offers no therapeutic or economic advantage over systemic administration of the same antibiotic. In addition, the use of irrigation in conjunction with systemic antibiotics does not enhance the efficacy of prophylaxis. Therefore, combining the two modalities is not justified (Elliott and Flaherty, 1986).

No randomized controlled trials of antibiotic prophylaxis in women having cesarean hysterectomy have been published. However, the frequency of pelvic infection after this procedure is similar to that after simple cesarean delivery. Accordingly, antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated when cesarean hysterectomy is performed, particularly on an emergency basis.

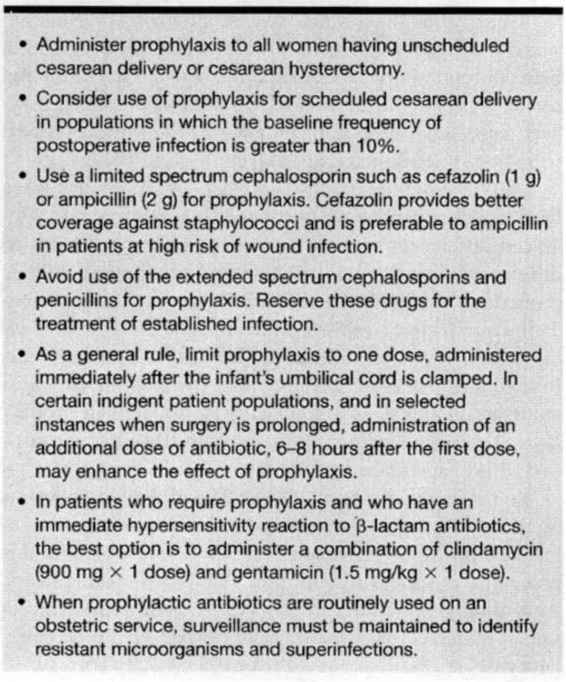

To date, serious maternal side effects of antibiotic prophylaxis have been exceedingly uncommon. Alterations in the vaginal flora clearly occur after prophylaxis. In particular, women who develop endometritis despite receiving prophylaxis are at increased risk for having enterococcal infections (Carlson and Duff, 1990; Gibbs and colleagues, 1981). In addition, a small number of women who receive prophylaxis have developed antibiotic-associated diarrhea and, in isolated instances, pseudomembranous enterocolitis (Arsura and coworkers, 1985). Fortunately, these complications have virtually always been amenable to therapy. These observations underline the importance of restricting the administration of antibiotics to those patients who clearly benefit from prophylaxis and limiting the number of infusions to a maximum of one to three doses. Table 35-1 summarizes current recommendations for the use of prophylactic antibiotics in women having cesarean delivery.

TABLE 35-1. Recommendations for Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Women Having Cesarean Delivery

PREGNANCY TERMINATION PROCEDURES

The frequency of endometritis after first-trimester suction curettage is approximately 1–3 percent. The rate of infection is higher after second-trimester procedures, ranging from 5 to 10 percent in most investigations (Grimes and associates, 1984). Aside from gestational age at the time of surgery, the principal risk factors for postabortal infection are prior history of pelvic inflammatory disease and presence of a sexually transmitted disease, such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, or of another infection such as bacterial vaginosis, at the time of the surgical procedure (Grimes, 1984; Sonne-Holm, 1981; Darj, 1987; and their colleagues).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree