Maternal:

Infection is frequently associated with preterm labour and can cause occasionally severe maternal illness and postnatally, endometritis is common. Caesarean section is more commonly used.

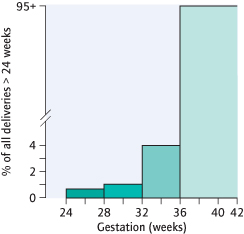

Aetiology of Spontaneous Preterm Labour (Fig. 23.3 )

Risk Factors

These are multiple and include a previous history, lower socioeconomic class, extremes of maternal age, a short inter-pregnancy interval, maternal medical disease such as renal failure, diabetes and thyroid disease, pregnancy complications such as pre-eclampsia or intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), male fetal gender, a high haemoglobin, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and vaginal infection (such as bacterial vaginosis), previous cervical surgery, multiple pregnancy, uterine abnormalities and fibroids, urinary infection, polyhydramnios, congenital fetal abnormalities and antepartum haemorrhage.

Mechanisms

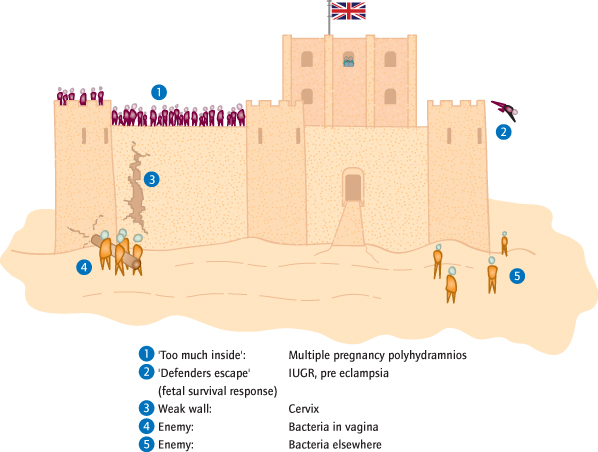

To rationalize these disparate risks, the uterus can be thought of as a castle, with the cervix as the castle wall holding the ‘defenders’ in (Fig. 23.3). Three groups of mechanisms, affecting the defenders, the castle walls or the enemy, lead to the wall being breached.

Too Many Defenders:

Multiple pregnancy is an increasing contributor because of assisted conception. Delivery before 34 weeks occurs in 20% of twins and is the mean time for delivery of triplets. Excess liquor, polyhydramnios [→ p.164] has the same effect, probably largely mediated by increased stretch.

The Defenders Jump Out:

The ‘fetal survival’ response. Spontaneous preterm labour is more common where the fetus is at risk, e.g. pre-eclampsia and IUGR, or if there is infection. Likewise, a placental abruption will often be followed by labour. Iatrogenic preterm delivery attempts to improve upon this mechanism.

The Castle Design Is Poor:

Uterine abnormalities such as fibroids or congenital (müllerian duct) abnormalities.

The Wall Is Weak:

The phrase ‘cervical incompetence’ unhelpfully describes the painless cervical dilatation that precedes some preterm deliveries. Some follow cervical surgery including treatments for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) [→ p.35] or cervical cancer, or multiple dilatations of the cervix [→ p.131], but in many no risk factors are known.

The Enemy Knock Down the Walls:

Infection is implicated in about 60% of preterm deliveries, and is often subclinical. Choriomanionitis, offensive liquor, neonatal sepsis and endometritis after delivery are all manifestations. Bacterial vaginosis is a well-known risk factor, but many bacteria including group B streptococcus (GBS) [→ p.167], Trichomonas, Chlamydia and even commensals have been implicated. The effects of infection are partly dependent on the cervix: whether a castle wall falls down depends on both its strength and that of the enemy. In practice, therefore, a cervical component and infection often coexist.

The Enemy Get Around the Walls:

Urinary tract infection and poor dental health (J Periodontol 2005; 76: 2144) are risk factors.

Prediction of Preterm Labour

History:

Those at increased risk (see above), particularly those with a previous history of late miscarriage or preterm labour, may undergo investigations and attempts to prevent preterm delivery. Nevertheless, most women who deliver preterm are not identified as high risk on history alone.

Investigations:

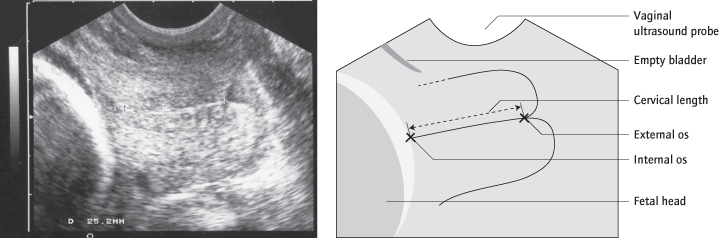

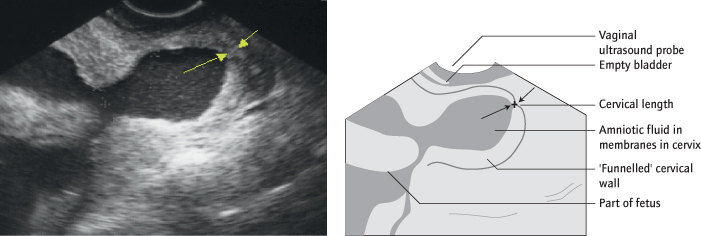

Even in women apparently at low risk for preterm delivery the cervical length on transvaginal sonography (TVS) (Figs 23.4, 23.5) is both sensitive and specific. Prediction is, however, not the same as prevention.

Prevention of Preterm Labour

Preventative strategies are usually limited to women at high risk. It is unclear if universal screening of all women with a cervical scan could lead to an overall reduction in the incidence of preterm labour. In women at high risk, because preterm labour is usually the culmination of events initiated many weeks earlier, strategies should begin by 12 weeks.

The Cervix

Cervical cerclage is the insertion of one or more sutures in the cervix to strengthen it and keep it closed (Fig. 23.6). It is commonly used although its effectiveness in isolation is disputed. The vaginal route is usual, but it can be placed abdominally if the cervix is very short or scarred. This is usually prepregnancy and can be laparoscopic. Cerclage is used in one of three situations. It can be elective, at 12–14 weeks, particularly in women with a history of preterm delivery. Or, the cervix can be scanned regularly and only sutured if there is significant shortening. Finally, it can be used as a ‘rescue suture’ that will, in expert hands, occasionally prevent delivery even when the ‘incompetent’ cervix is dilated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree