Chapter 37 Premalignant and malignant conditions of the female genital tract

CERVICAL PRECANCER AND CANCER

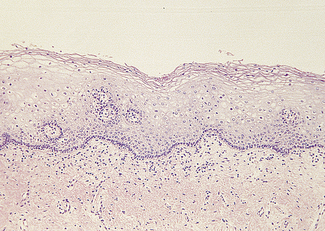

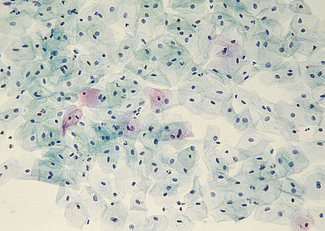

The cervical epithelium undergoes changes throughout the menstrual cycle and is readily accessible for examination. The epithelium covering the ectocervix is stratified and identical to that of the vagina (Fig. 37.1). It is separated from the underlying stroma by an apparent basement membrane. Superior to this is a layer of basal cells from which the other cell layers differentiate. Above the basal layer are five or six layers of parabasal cells. Above these are intermediate and superficial cell layers. The intermediate cell layer consists of large cells, each with reticulated nuclei and vacuoles of glycogen in the cytoplasm. The superficial cell layer varies in thickness, depending on the oestradiol : progesterone ratio. The superficial cells are flattened and have small nuclei, the cytoplasm containing glycogen (Fig. 37.2). A small amount of keratin is produced in some of the cells, which becomes ‘cornified’. During the reproductive years the superficial cells are constantly shed or exfoliated into the vagina, and differentiation of cells from the basal layer also proceeds constantly.

Epidemiology of cervical cancer

Cervical cancer occurs almost exclusively in women who are or have been sexually active. There is strong molecular biological and epidemiological evidence that the predominant cause of cervical cancer is sexually transmitted human papilloma virus (HPV). There are four HPV types that are considered to be high risk (16, 18, 45 and 56), a further 11 types that are intermediate risk (31, 33, 35, 39, 51, 52, 55, 58, 59, 66 and 68) and eight that are low risk (6, 11, 26, 42, 44, 54, 70 and 73) By the age of 35, 60% of sexually active women have acquired HPV infection of the genital tract (including the vulva). This proportion is higher if the woman or her partner has had several sexual partners. In most cases the infection is symptomless and disappears within a few months (see p. 258).

Cervical exfoliative cytology

The recommended smear regimen is summarised in Box 37.1. In women aged 30 and over, the doctor or nurse taking the smear should also examine the woman’s breasts, teach her breast self-examination, and after the age of 40 measure her blood pressure.

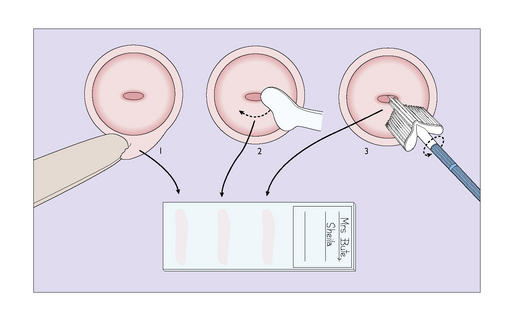

Technique for taking a cervical smear

A tray is provided on which a bivalve vaginal speculum, some slides, a spray-on fixative plastic, a modified Ayre spatula and an endocervical brush are placed. Before performing a vaginal examination, the warmed speculum is inserted to expose the cervix. The cytobrush is inserted into the cervical canal and rotated. The sample is smeared on to the slide. The ectocervix is sampled with the Ayre spatula or Cervex brush by rotating it twice through 360° and the sample is smeared on to a slide (Fig. 37.3). If liquid-based cytology is being used the brush is placed in the liquid medium.

The smears are sent to a reliable, quality assured cytological laboratory for examination.

REPORTING ON SMEARS

The Bethesda Classification

Squamous cell

New cervical screening techniques

Management of abnormal cervical smears

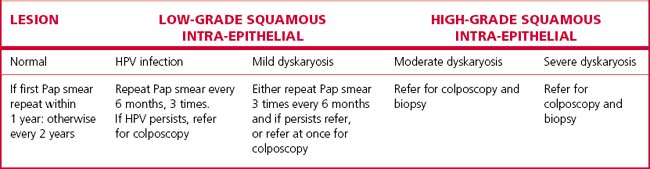

Approaches to the management of abnormal cervical smears are summarized in Table 37.1.

Mild dyskaryosis (predictive of CIN 1) with or without HPV

There are three potential management options:

Consequently the National Health and Medical research Council of Australia recommends option 1.