Background

Pregnant and postpartum women may be at increased risk of violent death including homicide and suicide relative to nonpregnant women, but US national data have not been reported since the implementation of enhanced mortality surveillance.

Objective

The objective of the study was to estimate homicide and suicide ratios among women who are pregnant or postpartum and to compare their risk of violent death with nonpregnant/nonpostpartum women.

Study Design

Death certificates (n = 465,097) from US states with enhanced pregnancy mortality surveillance from 2005 through 2010 were used to compare mortality among 4 groups of women aged 10–54 years: pregnant, early postpartum (pregnant within 42 days of death), late postpartum (pregnant within 43 days to 1 year of death), and nonpregnant/nonpostpartum. We estimated pregnancy-associated mortality ratios and compared with nonpregnant/nonpostpartum mortality ratios to identify differences in risk after adjusting for potential levels of pregnancy misclassification as reported in the literature.

Results

Pregnancy-associated homicide victims were most frequently young, black, and undereducated, whereas pregnancy-associated suicide occurred most frequently among older white women. After adjustments, pregnancy-associated homicide risk ranged from 2.2 to 6.2 per 100,000 live births, depending on the degree of misclassification estimated, compared with 2.5–2.6 per 100,000 nonpregnant/nonpostpartum women aged 10–54 years. Pregnancy-associated suicide risk ranged from 1.6–4.5 per 100,000 live births after adjustments compared with 5.3–5.5 per 100,000 women aged 10–54 years among nonpregnant/nonpostpartum women. Assuming the most conservative published estimate of misclassification, the risk of homicide among pregnant/postpartum women was 1.84 times that of nonpregnant/nonpostpartum women (95% confidence interval, 1.71–1.98), whereas risk of suicide was decreased (relative risk, 0.62, 95% confidence interval, 0.57–0.68).

Conclusion

Pregnancy and postpartum appear to be times of increased risk for homicide and decreased risk for suicide among women in the United States.

Improvements in maternal health care in the United States since the mid-1950s have drastically reduced mortality caused by hemorrhage, hypertension, complications of cesarean delivery, and other obstetric causes. Less attention has been paid to identifying and preventing injury-related fatalities and violent deaths including homicide and suicide among pregnant women and within the first year postpartum. Although pregnancy does not cause these deaths physiologically, it may be related to their occurrence, particularly for deaths resulting from intimate partner violence. Pregnancy does not appear to confer protection against victimization and in fact may add stress and exacerbate vulnerable circumstances in abusive relationships.

In an effort to encourage enhanced mortality monitoring beyond those deaths strictly classified as maternal, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defined pregnancy-associated mortality as the death of a woman while pregnant or within 1 year of the termination of pregnancy, regardless of the site or duration of the pregnancy and irrespective of the cause of death. Previous studies on pregnancy-associated mortality based on local city- or state-level data consistently find homicide ranks among the leading causes of death among women who are pregnant or recently postpartum, with variations by geographic area and demographic subgroup.

Despite the accumulating evidence of the magnitude of violent deaths, rigorous examination of mortality from nonobstetric causes in pregnancy and postpartum is rare, particularly in comparison with nonpregnant women. The 2003 revision to the US Standard Certificate of Death included an item to classify pregnancy status of a female decedent in the year preceding death to improve routine monitoring of pregnancy-associated mortality. Specifically, checkboxes identify the temporal relationship of death to pregnancy: during, within 42 days, or 43 days to 1 year after pregnancy.

Prior to the revision, ascertainment of pregnancy status differed across states, and although some states’ certificates included a pregnancy checkbox, cases of deaths occurring during and around the time of pregnancy were underreported, with evidence of more than 60% missing cases from some jurisdictions. National implementation of the 2003 revision has been incremental; by 2005, 22 jurisdictions had adopted the revision or maintained equivalent pregnancy items on death certificates. By 2010, the number had increased to 37.

The purpose of this analysis was to use these newly available data to describe mortality among 4 groups of reproductive-aged women in the United States from 2005 through 2010: pregnant, early postpartum (pregnant within 42 days of death), late postpartum (pregnant within 43 days to 1 year of death), and nonpregnant/nonpostpartum women. Second, we aimed to compare risk across demographic characteristics of victims of pregnancy-associated violent deaths and finally to determine whether pregnancy/postpartum represents a time of increased risk for violent death.

Materials and Methods

Study population

The National Center for Health Statistics provided death records for all women in 50 US states and the District of Columbia from 2005 through 2010, inclusive. For the purpose of this analysis, data were limited to women aged 10-54 years to ensure complete coverage of the population with reported pregnancy-associated deaths and to states and years with a temporal pregnancy item on death records that allowed for identification of decedents who were pregnant within 12 months of death (n = 465,097). This includes 36 states and the District of Columbia that had adopted the 2003 temporal pregnancy variable or retained equivalent items for at least 1 year ( Table 1 ). Nine states were excluded for lack of a pregnancy item on records for the study years, and the remaining 5 were excluded for records that captured pregnancy status only up to 90 days prior to death.

| Years | States |

|---|---|

| 2005–2010 | Connecticut, Florida, Idaho, Kansas, Michigan, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, Wyoming; excluded from proportionate mortality for lack of detailed temporality: California, Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Montana, Texas (2005 only) |

| 2006–2010 | District of Columbia, New Mexico, Oregon, Rhode Island |

| 2007–2010 | Delaware, Ohio |

| 2008–2010 | Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Nevada, North Dakota |

| 2009–2010 | Vermont |

| 2010 | Arizona, Missouri |

| Excluded from analysis | Cannot identify late postpartum (pregnancy within past 12 months): Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, Virginia Utilized pregnancy prompt, not question: Maine No pregnancy information: Alaska, Colorado, Hawaii, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, West Virginia, Wisconsin |

For jurisdictions with midyear implementation of the revision, we limited our analyses to the first full year of data. Five of the 37 included jurisdictions (California, Iowa, Kentucky, Minnesota for all study years and Texas until 2006) had items asking only whether the decedent had been pregnant within the past 12 months. These states were excluded from pregnant and postpartum proportionate mortality calculations. Where pregnant/postpartum status was unknown, we examined International Classification of Diseases , 10th revision, codes for underlying cause of death and identified additional maternal deaths based on codes within the Pregnancy, Childbirth, and the Puerperium classification. Where possible, these deaths were classified temporally ( Supplemental Table 1 ).

When temporality could not be determined, women were excluded from proportionate mortality calculations but were included in all analyses where pregnant and postpartum women were combined (pregnancy-associated mortality). The remaining women with an unknown pregnancy status were classified in the nonpregnant/nonpostpartum group. This analysis of deidentified death records was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Explanatory variables

We compared women across characteristics available on the death record: age (5 year age groups), race (non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, and other), marital status (married, not married), and education (less than high school; high school graduate or general education degree; higher than high school). Because the education item differs across death certificate versions, the continuous values from the 1989 certificate format (0 [no formal education] to 17 [5 or more years of college]) were grouped with the 2003 values as follows: 0–11 years with less than high school; 12 with high school graduate; and 13–17 with some college but no degree; associate’s, bachelor’s, master’s, or PhD degree all grouped as greater than high school.

Stratification by education status was limited to women who were ages 20 years or older at the time of death because younger women may not have completed educational attainment. International Classification of Diseases , 10th revision, codes for underlying cause of death were grouped as follows: natural (including obstetric and nonobstetric diseases and conditions), transport-related injury, other injury, homicide, suicide, and other external causes ( Supplemental Table 2 ).

Outcome measures

Pregnancy-associated homicide ratios were defined as the number of homicides among pregnant or postpartum women divided by the number of live births in states and years included in this analysis, available from annual natality data reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Likewise, pregnancy-associated suicide ratios were the number of suicides among pregnant or postpartum women divided by the number of live births from states and years included in this analysis. Given documented underreporting of pregnancy status on death records, we acknowledge that these mortality ratios are underestimates of the true rates of homicide and suicide in the peripartum period; however, their purpose is to illustrate the difference in risk across maternal demographic characteristics. Therefore, we present rate ratios (and 95% confidence intervals) for pregnancy-associated homicide and suicide by demographic characteristic rather than absolute rates.

Statistical analysis

To determine whether pregnancy and postpartum represents a time of increased risk for violent death, including homicide and suicide, we estimated the relative risks and 95% confidence intervals comparing pregnant/postpartum cases with nonpregnant/nonpostpartum cases with consideration for potential misclassification of pregnancy status.

The quality of death certification is largely determined by the care taken by the cause of death certifier to properly document the causes and circumstances of death. As such, ascertainment and reporting of pregnancy status is likely to vary across states. Fildes et al reviewed medical examiner records from 1986 through 1989 in Cook County, IL, and found that 65% of the deaths to women who were pregnant or postpartum were not identified as such on the death record.

More recently, Horon and Cheng quantified the underreporting of pregnancy/postpartum status on death certificates from 2001 through 2008 in Maryland. It is important to note that the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene implemented enhanced surveillance of pregnancy-associated death on death records beginning in 2001, and the Maryland Maternal Mortality Review Committee, established in 2000, performs a detailed case review, including review of medical examiner records and linkage of the women’s death certificates with birth and fetal death certificates from the prior year to enhance the accuracy of reporting. After rigorous case ascertainment through linkage of death records with medical examiner records and live birth and fetal death records, they reported that more than half (53.3%) of all pregnancy-associated deaths from nonobstetric causes were not recorded in the death record.

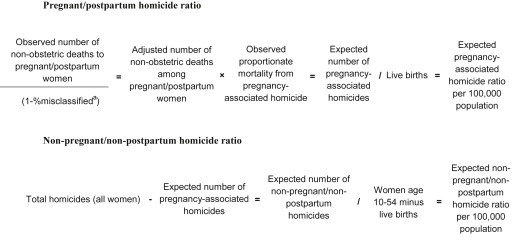

Therefore, we compared the risk of homicide and suicide between pregnant/postpartum women and nonpregnant/nonpostpartum women across potential misclassification scenarios ranging from unadjusted (0% misclassification) to the highest published reported rate of misclassification (65%). The Figure is a schematic of this procedure for homicide.

We applied the same methodology in estimating suicide risk. First, we identified the observed number of deaths due to nonobstetric causes among women reported as pregnant/postpartum. The number of misclassified deaths was estimated by dividing the observed number of nonobstetric deaths among pregnant/postpartum women by 1 minus the percentage misclassified in each scenario: 0%, 25%, 53%, and 65%. The estimated number of misclassified deaths was added to the total observed number of nonobstetric deaths in pregnant/postpartum women for an adjusted total. The adjusted total was multiplied by the observed proportionate mortality from homicide or suicide to derive an expected number of pregnancy-associated homicides and suicides.

The expected number of homicides or suicides among nonpregnant/nonpostpartum women was derived by subtracting the expected number among pregnant/postpartum women from the total homicides or suicides observed in the data. Pregnancy-associated homicide and suicide ratios were estimated by dividing the expected number of pregnancy-associated homicides and suicides by the total number of live births in states and years included in the analysis (n = 16,750,431). We divided the expected number of homicides or suicides in nonpregnant/nonpostpartum women by the number of women aged 10–54 years (total female population aged 10–54 years minus live births in states and years included in the analysis (n = 351,178,576). For ease of presentation, we refer to both the ratios as per 100,000 population.

Finally, we divided the ratio of homicide or suicide among pregnant/postpartum women by the corresponding ratio among nonpregnant/nonpostpartum women and calculated the 95% confidence interval to identify significant differences in risk between the 2 groups at each level of potential misclassification.

To explore whether differences in age distribution between pregnant/postpartum and nonpregnant/nonpostpartum decedents explained differences in homicide and suicide risk, we calculated age-adjusted mortality ratios for comparison by direct standardization using the age-specific crude rates of homicide and suicide (ie, without adjustment for pregnancy misclassification) among pregnant and nonpregnant women separately by age groups: <20, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–40, and ≥40 years. Age-specific mortality rates from both pregnant/postpartum and nonpregnant/nonpostpartum groups were applied to the 2000 US Standard Population to calculate the overall age-adjusted mortality ratios. It is important to note that age-adjusted ratios are intended for comparison only. Their values do not represent actual magnitude.

Results

There were 737,601 deaths of women aged 10-54 years in the United States from 2005 through 2010, and 465,097 (63.1%) occurred in jurisdictions and years included in this analysis. More than one third of the 465,097 deaths indicated a pregnancy status of unknown (n = 164,314; 35.3%) or not applicable (n = 16,006; 3.4%). Just more than 40% of the not applicable women were in the oldest age group (aged 50–54 years) and 80% were over the age of 40 years, suggesting a possible age-related medical reason for nonapplicability (hysterectomy, for example). Of the remaining 284,777 women, the vast majority were marked as not pregnant at the time of death or within the year preceding (n = 278,849, 97.9%).

We identified 5928 women who died during pregnancy or within 1 year in states and years included in this analysis, including 259 women with unknown status that were reclassified based on pregnancy-associated International Classification of Diseases , 10th revision, codes for underlying cause of death. Among 364,994 records from the 37 states with detailed temporality on death certificates, we identified 1858 women who died while pregnant (0.5%), 1225 within 42 days (0.3%), and 1466 in late postpartum (0.4%).

Proportionate mortality

A majority of deaths for all women were due to natural causes, including both obstetric and other nonobstetric conditions and diseases ( Table 2 ). Homicide was the third most frequent cause of death overall among pregnant women, with 190 cases over the 6 year period identifiable in these data, behind natural causes (n = 1150) and injuries (n = 430, transport-related and other injuries combined). Homicide accounted for 10.2% of mortality in pregnancy compared with 2.1% of mortality among nonpregnant women, 2.1% and 4.6% among early and late postpartum women, respectively.

| Not pregnant/not postpartum/unknown (n = 335,123) | Pregnant (n = 1858) | Early postpartum (n = 1225) | Late postpartum (n = 1466) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age, y c | ||||||||

| ≥35 | 275,464 | 82.2 | 638 | 34.3 | 405 | 33.1 | 452 | 30.8 |

| 30–34 | 19,086 | 5.7 | 287 | 15.5 | 256 | 20.9 | 255 | 17.4 |

| 25–29 | 15,223 | 4.5 | 359 | 19.3 | 264 | 21.6 | 316 | 21.6 |

| 20–24 | 12,665 | 3.8 | 379 | 20.4 | 230 | 18.8 | 327 | 22.3 |

| <20 | 12,685 | 3.8 | 195 | 10.5 | 70 | 5.7 | 116 | 7.9 |

| Race c | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 218,148 | 65.1 | 898 | 48.3 | 568 | 46.4 | 882 | 60.2 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 73,781 | 22.0 | 534 | 29.2 | 393 | 32.1 | 284 | 19.4 |

| Hispanic | 31,409 | 9.4 | 326 | 17.6 | 194 | 15.8 | 210 | 13.3 |

| Other | 11,785 | 3.7 | 91 | 4.8 | 70 | 5.7 | 90 | 6.1 |

| Education c | ||||||||

| Greater than high school | 119,792 | 35.8 | 643 | 34.6 | 477 | 38.9 | 514 | 35.1 |

| High school graduate or GED | 132,364 | 39.5 | 706 | 38.0 | 477 | 38.9 | 576 | 39.3 |

| Less than high school | 66,462 | 19.8 | 461 | 24.8 | 238 | 19.4 | 353 | 24.1 |

| Marital status c | ||||||||

| Married | 135,264 | 40.4 | 698 | 37.6 | 573 | 46.8 | 674 | 46.0 |

| Not married d | 189,668 | 56.6 | 1139 | 61.3 | 636 | 51.9 | 782 | 53.3 |

| Cause of death c | ||||||||

| Natural e | 258,707 | 77.2 | 1150 | 61.9 | 1018 | 83.1 | 925 | 63.1 |

| Transport injury | 20,766 | 6.2 | 323 | 17.4 | 53 | 4.3 | 181 | 12.4 |

| Other injury f | 28,695 | 8.6 | 107 | 5.8 | 75 | 6.1 | 161 | 11.0 |

| Homicide | 7160 | 2.1 | 190 | 10.2 | 26 | 2.1 | 68 | 4.6 |

| Suicide | 14,489 | 4.3 | 70 | 3.8 | 32 | 2.6 | 102 | 7.0 |

| Other external cause g | 5306 | 1.6 | 18 | 1.0 | 21 | 1.7 | 29 | 2.0 |

a Limited to states and years with detailed temporal pregnancy information on death records (see Table 1 )

b Proportions do not sum to 100 where data are unknown or missing

d Not married includes women who were single, divorced, or widowed

e Natural includes diseases and conditions related and unrelated to pregnancy, childbirth, or the puerperium. Refer to Table 2 for specific ICD-10 codes

f Other injuries include falls; accidental poisoning by and exposure to noxious substances; drowning and other threats to breathing; exposure to inanimate mechanical forces; electrical currents, smoke, and fire; forces of nature; and other unspecified. Refer to Table 2 for specific ICD-10 codes

g Other external causes of death include events of undetermined intent (poisoning, drowning, firearm, fire, and other unspecified), legal intervention, and complications of medical and surgical care. Refer to Table 2 for specific ICD-10 codes.

Suicide was the third most frequent cause of death among both early and late postpartum women behind natural causes and injuries. There were 70 women who died by suicide while pregnant, 32 in early postpartum, and 102 among late postpartum women, the group with the highest proportion of deaths attributable to suicide (7.0%) across the 4 groups.

Pregnancy-associated homicide

There were a total of 364 pregnancy-associated homicides reported in the death records that captured pregnancy status in the previous 12 months. The majority (56.3%) were firearm related. Adolescents were at the highest risk for pregnancy-associated homicide compared with women of any other age group ( Table 3 ), with a greater than 2-fold increase compared with women over age 35 years. Pregnancy-associated homicide was greater than 3 times more likely to occur in non-Hispanic black women compared with non-Hispanic whites. Education was inversely related to homicide risk such that all women with at least some higher education were at lower risk relative to women with a high school education or less among those who died at age 20 years and older. Finally, risk of pregnancy-associated homicide among unmarried women was more than 5 times the risk in married women.

| Live births a | Pregnancy-associated homicide | Pregnancy-associated suicide | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | RR | 95% CI | N | % | RR | 95% CI | |||

| Age, y | ||||||||||||

| ≥35 | 2,481,833 | 14.8% | 45 | 12.4% | Referent | 53 | 20.2% | Referent | ||||

| 30–34 | 3,887,668 | 23.2% | 46 | 12.6% | 0.65 d | 0.43 d | 0.98 d | 45 | 17.1% | 0.54 d | 0.36 d | 0.81 d |

| 25–29 | 4,675,226 | 27.9% | 92 | 25.3% | 1.09 | 0.76 | 1.55 | 66 | 25.1% | 0.66 d | 0.46 d | 0.95 d |

| 20–24 | 4,054,251 | 24.2% | 111 | 30.5% | 1.51 d | 1.07 d | 2.14 d | 71 | 27.0% | 0.82 | 0.57 | 1.17 |

| <20 | 1,651,453 | 9.9% | 70 | 19.2% | 2.34 d | 1.61 d | 3.40 d | 28 | 10.6% | 0.79 | 0.50 | 1.26 |

| Race | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 8,386,423 | 50.1% | 146 | 40.1% | Referent | 166 | 63.1% | Referent | ||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 2,167,903 | 12.9% | 125 | 34.3% | 3.31 d | 2.61 d | 4.21 d | 21 | 8.0% | 0.49 d | 0.31 d | 0.77 d |

| Hispanic | 4,853,021 | 29.0% | 87 | 23.9% | 1.03 | 0.79 | 1.34 | 46 | 17.5% | 0.48 d | 0.35 d | 0.66 d |

| Other | 1,343,084 | 8.0% | 6 | 1.6% | 0.26 d | 0.11 d | 0.58 d | 27 | 10.3% | 1.02 | 0.68 | 1.53 |

| Education b | ||||||||||||

| Greater than high school | 5,738,796 | 56.1% | 84 | 29.0% | Referent | 115 | 50.2% | Referent | ||||

| High school graduate or GED | 2,685,940 | 26.2% | 121 | 41.7% | 3.08 d | 2.33 d | 4.07 d | 74 | 32.3% | 1.37 d | 1.03 d | 1.84 d |

| Less than high school | 1,808,410 | 17.7% | 85 | 29.3% | 3.21 d | 2.38 d | 4.34 d | 40 | 17.5% | 1.10 | 0.77 | 1.58 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Married | 10,126,699 | 60.5% | 78 | 21.4% | Referent | 108 | 41.1% | Referent | ||||

| Not married c | 6,623,732 | 39.5% | 284 | 78.0% | 5.57 d | 4.33 d | 7.15 d | 153 | 58.2% | 2.17 d | 1.69 d | 2.77 d |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree