KEY POINTS

• Life-threatening emergencies and serious complications may occur during the postpartum period. These must be recognized and managed efficiently.

• Health care providers caring for postpartum women should be sensitive to the initiation of family bonding, a special process that should not be disturbed unless maternal or neonatal complications arise.

BACKGROUND

Definition

The postpartum period is traditionally defined as the 6 weeks following parturition.

Pathophysiology

Reproductive Organs

• Contraction of the uterine myometrium occurs immediately after delivery of the placenta and serves to compress dilated vessels supplying the placental site. By 2 weeks postpartum, the uterus involutes sufficiently to again be a pelvic organ, and by 4 weeks postpartum, the uterus returns to nonpregnant dimensions. Within days of delivery, the superficial decidua necroses and sloughs in the form of lochia. New endometrium is regenerated from the basal layer within 7 to 10 days, with the exception of the placental site. The placental site is slowly exfoliated by the undermining growth from the surrounding regenerating endometrium.

• The cervix regains tone within 2 to 3 days after delivery and remains dilated 2 to 3 cm. By 1 week postpartum, the cervix regains a nonpregnant appearance.

• The vagina remains edematous and enlarged for approximately 3 weeks. Involution is usually complete by 6 weeks postpartum.

• Ovulation occurs on the average at 10 weeks in the nonlactating woman (1). The first menstrual cycle is frequently anovulatory. In nonlactating women, the mean time to first menses is 7 to 9 weeks, and 70% will menstruate by 12 weeks postpartum (2). In lactating women, time to ovulation and menstruation is highly variable and depends on the duration and frequency of breast-feeding.

• The breasts are prepared for lactation during pregnancy by estrogen, progesterone, cortisol, prolactin, placental lactogen, and insulin, while actual lactation is suppressed by high levels of placental steroids. The rapid fall in progesterone postpartum allows expression of α-lactalbumin, which stimulates milk lactose production and initiates lactation. Initial milk production consists mostly of colostrum, which is richer in proteins and immunoglobulins than is mature milk. Prolactin appears to be the single most important maintenance hormone necessary for continued milk production (3).

Systemic Changes

• Circulating blood volume returns to nonpregnant levels by the 10th day postpartum. Dilated blood vessels supplying the uterus during pregnancy undergo involution, and extrauterine vessels decrease their diameter to nonpregnant dimensions. In contrast, cardiac output increases immediately after delivery but then slowly declines, reaching late pregnancy levels 2 days postpartum and decreasing by only 16% 14 days after delivery (4). This occurs as a consequence of increased stroke volume from increased venous return, despite a quick fall in the pulse rate by about 10 beats/min.

• The bladder demonstrates increased capacity and decreased volume sensitivity. This may result in transient urinary retention. This is also aggravated by increased urine production as a consequence of infused fluid during labor and withdrawal of the antidiuretic effect of oxytocin administered in large doses after delivery. Renal function decreases to nonpregnant levels by 6 weeks postpartum. A postpartum diuresis occurs within 1 to 2 weeks after delivery and compensates for water retention during pregnancy. Anatomic changes of pregnancy such as ureteral and calyceal dilatation may persist for several months.

• The enlarged thyroid gland returns to prepregnancy dimensions over a 12-week period (5). Previously increased thyroid-binding globulin, total thyroxine, and total triiodothy-ronine return to normal levels by 4 to 6 weeks postpartum.

• In late pregnancy, the pancreas exhibits an enhanced insulin response to glucose challenge, accompanied by higher postprandial glucose levels. The insulin response curve returns to the nonpregnant state 2 days after delivery. The glucose curve normalizes by 8 to 10 weeks postpartum.

• Hemoglobin concentration rises on the first postpartum day and then decreases, reaching a nadir on the 4th or 5th day. A gradual increase in hemoglobin then ensues, approaching day 1 values on the 9th day. Mean leukocyte count steadily increases during pregnancy, reaching about 10,000 in the third trimester. There is a further increase during and immediately after delivery. The leukocyte count returns to nonpregnant values by the 6th day postpartum. Platelet count, in contrast, decreases steadily during pregnancy. For 2 days after delivery, platelets decrease further and then rise rapidly thereafter secondary to release of fresh platelets with increased adhesiveness. A hypercoagulable postpartum state results and lasts about 7 weeks. Several clotting factors including fibrinogen rise during first postpartum days. The fibrinolytic enzyme system, on the other hand, is depressed during pregnancy but returns rapidly to the nonpregnant state after delivery.

NORMAL POSTPARTUM CARE

History and Physical

• Vital signs should be assessed every 4 hours for the first 24 hours, including measurement of urine output.

• Uterus and lochia

• The quantity of bleeding in the first several days postpartum should be similar to the menses. The uterus should be slightly below the umbilicus and firm. If it is not, the patient may be experiencing significant bleeding, either concealed in the uterus or in the vagina. The uterus should be evaluated for any unusual degree of tenderness that might suggest endometritis.

• Lochia should be assessed for unusual odor. Lochia rubra, seen for the first several days, consists mainly of blood and necrotic decidual tissue. Lochia serosa follows and is lighter, as there is less blood. After several weeks, the patient notices only a leukorrhea known as lochia alba.

• Immediately postpartum, nursing staff and patients should be instructed to perform uterine massage to decrease uterine bleeding.

• The abdomen should be examined for distension and the presence of bowel sounds, especially in patients who had cesarean deliveries.

• Postcesarean patients usually experience a return of coordinated bowel function by the 2nd or 3rd day. Failure to do so strongly suggests an ileus.

• Following cesarean section, oral intake may resume immediately as tolerated. Early feeding has been shown to shorten hospital stay without increasing vomiting or ileus in women after major abdominal gynecologic surgery (6).

• The perineum should be inspected for hematoma formation, signs of infection, or breakdown. Hemorrhoids may also be noted on examination.

• Perineal care consists of gentle cleansing and warm sitz baths initiated on the first postpartum day.

• Local anesthetics such as witch hazel pads or benzocaine spray may be used. Hydrocortisone and local anesthetic preparations may be applied to hemorrhoids.

• Stool softeners such as docusate sodium and osmotic laxatives are usually prescribed, especially in cases of third or fourth degree lacerations. Shorter-interval follow-up is recommended for these patients.

• Bladder function should be assessed by noting urine output and any symptoms of urinary retention.

• Patients at risk for urinary retention include those receiving regional anesthesia and/or experiencing perineal pain from genital tract injury at delivery. Catheterization may be required if the patient is unable to void within 6 hours. Failure to urinate for greater durations of time increases the risks of bladder dysfunction.

• Postcesarean section patients generally have their Foley catheter removed approximately 18 to 24 hours after surgery. It may be removed once the effects of regional anesthesia have disappeared and there are no signs of internal hemorrhage.

• Anatomical barriers to successful breast-feeding should be identified. Observation of a nursing session can distinguish patients likely to benefit from lactational support. The breasts should be examined for engorgement or signs of infection.

• The lungs should be evaluated in all postpartum patients because they are an important source of postoperative fever.

• Patients should receive instruction and encouragement in the use of incentive spirometry during the postoperative period. Use of splinting during coughing can minimize pain associated with this important aspect of pulmonary function.

• The extremities should be evaluated for signs of increasing edema and calf pain.

• Unilateral edema and calf pain warrant investigation for thrombus.

Lactational Support

Background

• Human milk is the preferred infant nutrition except in very rare infant metabolic disorders (7).

• There are numerous infant and maternal benefits to human milk and breast-feeding. These include decreased infant infection and infant mortality, decreased chronic childhood diseases, and decreased childhood obesity. Maternal benefits include a decrease in postpartum hemorrhage, a lower average weight compared to non–breast-feeding women, and possibly decrease in breast and ovarian cancer (7,8).

• Maternal milk obtained by either direct breast-feeding or expression is encouraged except in cases of maternal HIV or certain maternal medication/drugs. These drugs include chemotherapeutic, anticonvulsant, and psychiatric medications or illicit drugs and should be carefully evaluated on an individual basis.

• Infant feeding should be initiated within 1 hour of birth.

• On-demand feeding, or unrestricted nursing, ensures an adequate supply of milk is available for the infant.

• Infants innately possess the reflexes that confer the ability to breast-feed—rooting, suckling, and swallowing.

• A good infant latch is imperative to successful breast-feeding.

• Much of the areola of the mother’s nipple should be included in the infant’s mouth during suckle, which places the nipple at the infant’s hard palate.

• Patients who elect not to breast-feed should have their breasts tightly bound to inhibit lactation.

• Bromocriptine is no longer used to suppress lactation due to reported cases of hypotension, hypertension, seizures, and strokes (9).

• Every effort should be made to provide a postpartum atmosphere that supports breastfeeding, including lactational consultants if available.

• Ongoing support will need to be provided throughout the duration of breast-feeding especially if a mother will be physically absent for long periods of time such as returning to work.

• Evaluation of infant latch should be observed early when feeding concerns occur.

• Large breasts, previous breast surgery, or inverted nipples can make latch difficult and may require supportive care or education on positioning.

• Infant anatomical abnormalities such as cleft lip/palate, restrictive frenulum, and muscular weakness can cause difficult nursing and should be evaluated for treatment.

• Appropriate breast care during lactation can ensure the nipples remain pain free.

• Breast support should not include underwire, and lanolin cream can ease soreness.

• Cracked nipples should be evaluated promptly for infection.

• If there is a concern for low supply of breast milk, galactogogues such as metoclopramide or domperidone can be used to stimulate lactation.

• Should breast-feeding prove very difficult, the patient should be educated on expression of breast milk either manually or via electric pump to be fed to the infant.

• Breast engorgement can occur resulting in maternal discomfort or poor infant latch.

• This may need to be relieved by either manual expression or use of a breast pump.

• Development of a clogged lactational duct can cause maternal pain and should be treated with continued nursing or milk expression.

• Warm compresses and gentle massage of the area are important if a palpable lump is present.

• It is imperative to differentiate this from mastitis, which is discussed more extensively in the section on postpartum infection.

Laboratory Tests and Immunizations

• Complete blood count on the first postpartum day.

• Blood type and screen (to administer RhoGAM to nonsensitized Rh-negative patients).

• Rubella titer if not previously known, to assess need for immunization postpartum.

• Influenza and TDap vaccination are universally recommended in the postpartum period if not administered antepartum (10–12).

COMPLICATIONS IN POSTPARTUM CARE

Postpartum Hemorrhage

Background

• Hemorrhage is the most common cause of maternal mortality worldwide.

• Postpartum hemorrhage has been defined as either a 10-point decrease in hematocrit between admission and postpartum or a need for erythrocyte transfusion. The classical definition of postpartum hemorrhage of total blood loss greater than 500 mL at vaginal delivery and greater than 1000 mL at cesarean delivery suffers from the limitations of clinical estimation of blood loss during delivery. Average blood loss following vaginal delivery, cesarean section, and cesarean hysterectomy was estimated by Pritchard et al. (13) to be approximately 500, 1000, and 1500 mL, respectively. It has been demonstrated that assessment of blood loss during delivery is oftentimes underestimated (14).

Differential Diagnosis

Early

• Atony (in about 90% of patients)

• Genital tract trauma (in about 7%)

• Coagulopathy (in about 2% to 3%)

• Retained placental fragments, placenta accreta, increta, and percreta

• Uterine inversion (rare)

• Uterine rupture

Late

• Retained placental fragments

• Subinvolution of the placental bed

• Endomyometritis

• Coagulopathy

Treatment

Prevention

• Avoid genital tract trauma.

• Prophylactically use oxytocic agents at the onset of the third stage of labor.

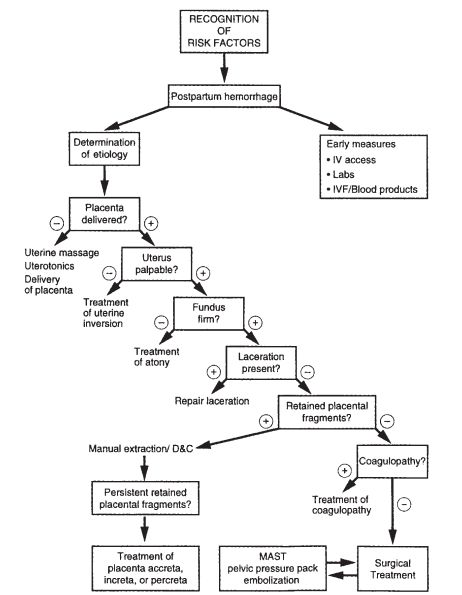

• Actively manage the third stage of labor (with controlled cord traction after signs of placental separation have occurred) (15) (Fig. 4-1).

Figure 4-1. Management of postpartum hemorrhage.

Uterine Atony

Background

• Uterine atony is responsible for approximately 90% of postpartum hemorrhages.

Diagnosis

• The diagnosis is usually made in the presence of a soft uterus on abdominal examination and vaginal bleeding.

• Risk factors include polyhydramnios, multiple gestation, fetal macrosomia (probably secondary to uterine over distention), rapid or prolonged labor, oxytocin use, high parity, chorioamnionitis, and myometrial relaxing agents (magnesium sulfate, terbutaline, halogenated anesthetic agents, and nitroglycerine) (16,17).

Treatment

Massage

• Bimanual uterine massage is performed by applying compression between a hand on the abdomen and a hand in the vagina.

Medications

• If massage is unsuccessful, the next measure is medical therapy. Many labor and delivery units have an emergency medicine kit that is readily accessible in these situations. The following are commonly used uterotonic agents that can be administered once drugspecific contraindications are identified (14).

• Oxytocin intravenously (10 to 40 U/L up to 500 mL in 10 minutes), intramuscularly, or intramyometrially (10 U). There are no contraindications to the use of oxytocin. Side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and water intoxication secondary to its antidiuretic effect are rare.

• Methylergonovine intramuscularly, intravenously, or intramyometrially (0.2 mg every 2 to 4 hours). Methylergonovine is contraindicated in patients with hypertension. Side effects of hypertension, hypotension, nausea, and vomiting have been reported.

• 15-Methylprostaglandin F2α intramuscularly or intramyometrially (0.25 mg every 15 to 90 minutes up to 8 doses). This medication has been used to correct uterine atony unresponsive to other agents (18,19). Prostaglandins of the F series should be used with great caution in patients with bronchospasm, renal or hypertensive disorders, and pulmonary hypertension. Common side effects including fever, vomiting, diarrhea, hot flushes, and chills. Prostaglandins can also cause bronchoconstriction, pulmonary vasoconstriction, hypotension, hypertension, and arterial oxygen desaturation.

• Prostaglandin E2 (dinoprost) is administered as a vaginal or rectal suppository (20 mg every 2 hours). It may be particularly helpful in cases of refractory, persistent postpartum atony (20). It does not cause severe pulmonary vasocongestion or bronchoconstriction, thus providing a potentially safer alternative for patients with heart and lung disease. It shares other side effects with prostaglandin F2α and has been reported to cause vasodilation and hypotension.

• Prostaglandin E1 (misoprostol) 800 to 1000 mcg rectally once. It is most likely to cause GI distress, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or fever. Shares side effects such as hypotension common to the prostaglandins.

Uterine Tamponade

• When uterotonics do not provide adequate uterine contraction to inhibit bleeding, uterine tamponade can provide direct pressure especially to temporize and reduce blood loss (14).

• Uterine packing with 4-inch gauze with or without thrombin can reduce blood loss especially if tightly packed. If thrombin is available, the gauze can be soaked in a solution of 5000 U of thrombin in 5 mL saline.

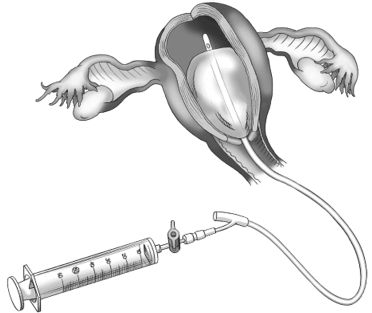

• Commercial balloon tamponade devices such as the Bakri (Fig. 4-2) or Ebb balloons can be inserted up to the uterine fundus and filled with saline to provide direct intrauterine pressure (21).

Figure 4-2. Bakri tamponade balloon. (Lippincott’s Nursing Advisor 2013. Available at: http://thepoint.lww.com. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013.)

Surgery

• Surgical intervention via laparotomy is indicated when uterine bleeding does not respond to massage or medication. Each of these interventions may also be performed at the time of cesarean delivery.

• The B-Lynch stitch was first described by Christopher B-Lynch (22–24) and is a useful tool in the armamentarium for uterine atony because it is simple to apply, preserves fertility, and does not obliterate the uterine or cervical lumen. The utility of the technique is first verified by an assistant who observes resolution of vaginal bleeding under the operative drape as the surgeon applies manual compression to the atonic uterus on the surgical field. The hysterotomy incision is then reopened, and a 36-inch suture of chromic catgut is obtained. Due to the tension placed on the suture, the suture must be at least of 2-0 size. The suture is placed anterior across the hysterotomy incision and is brought up over the uterine fundus (Fig. 4-3A). The next surgical bite is placed horizontally in the posterior aspect of the uterus, at the level of the uterine incision (Fig. 4-3B). The suture is then returned over the contralateral side of the uterine fundus to the anterior lower uterine segment. The third surgical bite is then made perpendicular across the hysterotomy incision and the suture tied below the incision, achieving manual uterine compression (see Fig. 4-3C).

• Uterine artery ligation was first described by O’Leary and O’Leary (25) and has proven to be safe, easily performed, often effective, and preservative of fertility. The technique, designed to control postcesarean hemorrhage, uses single mass ligation of the uterine artery and vein with a no. 1 chromic suture on a large atraumatic needle placed at the level of the vesicouterine peritoneal reflection. The vessels are not divided, and recanalization with subsequent normal pregnancy can be expected (26). When combined with ligation of utero-ovarian vessels, the procedure has been reported to be successful in 95% of cases. Both procedures work by reducing uterine perfusion. Bilateral ovarian artery ligation may adversely affect future fertility and does not enhance the effectiveness of the preceding measures because more than 90% of the uterine blood flow in pregnancy passes through the uterine arteries.

• Bilateral hypogastric artery ligation is indicated in hemodynamically stable patients with placenta accreta, uterine atony, or laceration associated with uterine incision when future fertility is of great concern. It reduces pulse pressure to pelvic organs. Its success rate is reported to be less than 50%. It is performed after division of the round ligament and exposure of the pelvic side wall (27). Clinically it requires advanced surgical skills and is a rarely utilized technique as its success rate is less than 50%.

• Hysterectomy is used to treat postpartum hemorrhage when other surgical techniques have failed. It is thus the procedure of choice in unstable patients or to stop very severe bleeding. In many situations, a supracervical hysterectomy is sufficient and preferred. Clark et al. (28

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree