5.3 Poisoning and envenomation

Poisoning

Management

Support vital functions

It is imperative to maintain and support vital functions if these are depressed. Many poisons are excreted adequately or metabolized by the body if the vital functions are maintained. If the patient is unconscious, the airway, the depth and frequency of breathing, and the circulation should be examined for adequacy. Chapter 5.2 provides a full discussion on the management of deficiencies of the airway, breathing and circulation.

Prevent absorption

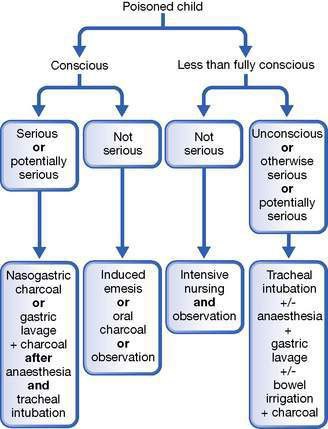

Circumstances of presentation and ingestion dictate the choice of technique.

Activated charcoal is probably the most appropriate therapy in the emergency department, although whole bowel irrigation may be preferable for some agents. Gastric lavage should be reserved for a recent (within 1 hour) serious life-threatening ingestion in a conscious patient or for serious poisoning in a less than fully conscious patient who has airway protection. It is preferable that all patients undergoing gastric lavage have the airway protected with endotracheal intubation. The circumstances for the employment of each technique are summarized in Figure 5.3.1.

Administer an antidote

Only relatively few poisons have antidotes, but knowledge and use of these can be life-saving. The appropriate dose of each is determined by the amount of poison and its effects. A list of common important antidotes is given in Table 5.3.1.

Table 5.3.1 Antidotes to some serious poisons

| Poison | Antidotes | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Amphetamines | Esmolol i.v. 500 μg/kg over 1 min, then 25–200 μg/kg/min Labetalol i.v. 0.15–0.3 mg/kg or phentolamine i.v. 0.05–0.1 mg/kg every 10 min Diazepam 0.2 mg/kg i.v. | Treatment for tachyarrhythmia Treatment for hypertension Controls agitation, aggression |

| Benzodiazepines | Flumazenil i.v. 3–10 μg/kg, repeat 1 min, then 3–10 μg/kg/h | Specific receptor antagonist |

| Beta-blockers | Glucagon i.v. 140 μg/kg, then 0.2–1 μg/kg/min Isoprenaline i.v. 0.05–3 mg/kg/min Noradrenaline (norepinephrine) i.v. 0.05–1 μg/kg/min | Stimulates non-catecholamine cAMP, preferred antidote Beware hypotension |

| Calcium channel blocker | Calcium chloride i.v. 10%, 0.2 mL/kg | |

| Carbon monoxide | Oxygen 100% | Decreases carboxyhaemoglobin. May need hyperbaric oxygen |

| Cyanide | Dicobalt edetate i.v. 7.5 μg/kg (max 300 mg) over 1 min, then 300 mg at 5 min Sodium nitrite 3% i.v. 0.33 mL/kg over 4 min, then sodium thiosulphate 25% i.v. 1.65 mL/kg (max 50 mL) at 3–5 min | Give 50 mL 50% glucose after each dose Nitrites form methaemoglobin–cyanide complex. Beware excess methaemoglobin > 20% Thiosulphate forms non-toxic thiocyanate from methaemoglobin–cyanide |

| Digoxin | Magnesium sulphate i.v. 25–50 mg/kg (0.1–0.2 mmol/kg) Digoxin Fab i.v: acute − 10 vials per 25 tablets (0.25 mg each), 10 vials per 5 mg elixir; steady state − vials = serum digoxin (ng/mL) × BW (kg)/100 | |

| Ergotamine | Sodium nitroprusside infusion 0.5–5.0 μg/kg/min Heparin i.v. 100 units/kg then 10 30 units/kg/h | Treats vasoconstriction. Monitor BP continuously Monitor partial thromboplastin time |

| Heparin | Protamine 1 mg/100 units heparin | |

| Iron | Desferrioxamine 15 mg/kg/h over 12–24 h if serum iron > 90 or > 63 μmol/L and symptomatic | Give slowly; beware anaphylaxis |

| Lead | Dimercaprol (BAL) i.m. 75 mg/m2 4-hourly for 6 doses then i.v. CaNa2 edetate (EDTA) 1500 mg/m2 over 5 days if blood level > 3.38 μmol/L. If asymptomatic and blood level 2.65–3.3 μmol/L, infuse CaNa2 EDTA 1000 mg/m2/day over 5 days or oral succimer 350 mg/m2 8-hourly over 5 days, then 12-hourly over 14 days | |

| Methaemoglobinaemia | Methylene blue i.v. 1–2 mg/kg over several minutes | |

| Methanol, ethylene glycol, glycol ethers | Ethanol i.v. loading dose 10 mL/kg 10% diluted in glucose 5%, then 0.15 mL/kg/h to maintain blood level 0.1% (100 mg/dL) | |

| Opiates | Naloxone i.v. 0.01–0.1 mg/kg, then 0.01 mg/kg/h as needed | |

| Organophosphates and carbamates | Atropine i.v. 20–50 μg/kg every 15 min until secretions dry Pralidoxime i.v. 25 mg/kg over 15–30 min then 10–20 mg/kg/h for 18 h or more. Not for carbamates | Blocks muscarinic effects Reactivates cholinesterase |

| Paracetamol | N-acetylcysteine i.v. 150 mg/kg over 60 min then 10 mg/kg/h for 20–72 h or oral 140 mg/kg, then 17 doses of 70 mg/kg 4-hourly (total 1330 mg/kg over 68 h) | Restores glutathione, inhibits metabolites. Give within 18 h according to serum paracetamol level |

| Phenothiazine dystonia | Benztropine i.v or i.m. 0.01–0.03 mg/kg | Blocks dopamine reuptake |

| Potassium | Glucose i.v. 0.5 g/kg plus insulin i.v. 0.05 units/kg Salbutamol aerosol 0.25 mg/kg Sodium bicarbonate i.v. 1 mmol/kg Calcium chloride 10% i.v. 0.2 mL/kg Resonium oral or rectal 0.5–1 g/kg | Decreases serum potassium rapidly. Monitor serum glucose levels Decreases serum potassium rapidly Decreases serum potassium slightly; beware hypocalcaemia Antagonizes cardiac effects Adsorbs potassium slowly |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Sodium bicarbonate i.v. 1 mmol/kg to maintain blood pH > 7.45 | Reduces cardiotoxicity |

BW, body weight; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; EDTA, ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree