Chapter 404 Pleurisy, Pleural Effusions, and Empyema

Pleurisy or inflammation of the pleura is often accompanied by an effusion. The most common cause of pleural effusion in children is bacterial pneumonia (Chapter 392); heart failure (Chapter 436), rheumatologic causes, and metastatic intrathoracic malignancy are the next most common causes. A variety of other diseases account for the remaining cases, including tuberculosis (Chapter 207), lupus erythematosus (Chapter 152), aspiration pneumonitis (Chapter 389), uremia, pancreatitis, subdiaphragmatic abscess, and rheumatoid arthritis. Males and females are affected equally.

404.1 Dry or Plastic Pleurisy (Pleural Effusion)

Glenna B. Winnie and Steven V. Lossef

Laboratory Findings

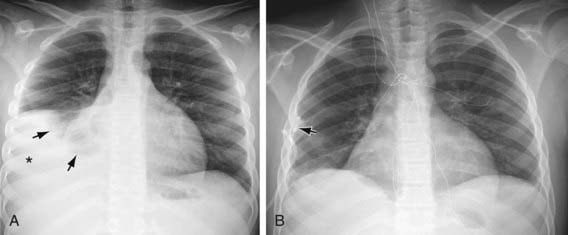

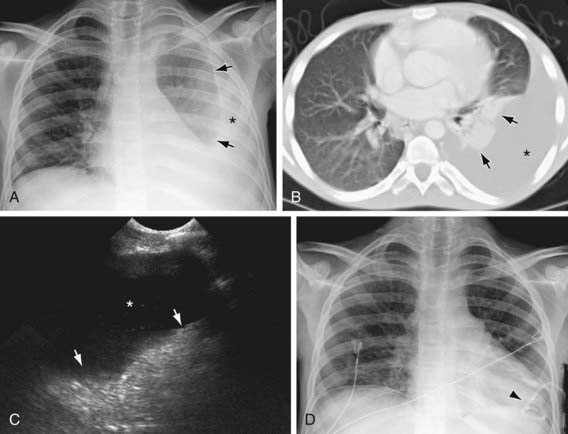

Plastic pleurisy may be detected on radiographs as a diffuse haziness at the pleural surface or a dense, sharply demarcated shadow (Figs. 404-1 and 404-2). The latter finding may be indistinguishable from small amounts of pleural exudate. Chest radiographic findings may be normal, but ultrasonography or CT findings will be positive.