On successfully completing this topic, you will be able to:

recognise risk factors for a morbidly adherent placenta

understand the need for a multidisciplinary plan of management where accreta is suspected

understand the technique of manual removal of the placenta.

Introduction

Postpartum haemorrhage is a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Chapter 25 has covered the management of major obstetric haemorrhage; this chapter will look at the management of problems associated with an adherent placenta, where separation does not occur and manual removal is required or where the placenta is morbidly adherent.

Placenta accreta

Definition and incidence

Normally, the placenta does not penetrate deeper than the decidua basalis. If it invades further it will be morbidly attached, and heavy bleeding is likely if separation is attempted. The terms placenta accreta, increta and percreta refer to deeper penetration of the chorionic villi into, and ultimately through, the myometrium and possibly into adjacent organs, such as the bladder. In this chapter, placenta accreta will be used to refer to all grades of abnormal penetration.

The incidence is rising and is currently 2 per 1000 deliveries. It is usually associated with previous surgery to the uterus – most commonly a CS. The risk of accreta rises with the number of previous caesarean sections, and is greatest when associated with placenta praevia. If a woman having her third CS has a placenta praevia, she has a 40% chance of a placenta accreta. In the 2005–06 UK Obstetric Surveillance System study of peripartum hysterectomy, 39% of women having this operation had a morbidly adherent placenta, and the main risk factor was a previous CS.

The 2009–2012 confidential enquiry reported one death from placenta accreta.

Diagnosis

All women who have had a previous CS should undergo ultrasound assessment of the placental site, even if they decline an anomaly scan. If the placenta is anterior and appears to cover the scar (i.e. reaches the internal cervical os), the scan should be repeated at 32 weeks. Sonographic features that suggest accreta are:

a loss of the hypoechoic retroplacental zone

multiple vascular lacunae in the placenta giving a ‘Swiss cheese’ appearance

blood vessels or placental tissue bridging uterine–placental margin, myometrial–bladder interface or crossing uterine serosa

retroplacental myometrial thickness of <1mm

numerous coherent vessels visualised with 3D power Doppler in basal view.

Studies suggest that colour Doppler has the highest sensitivity and moderate specificity.

MRI is recommended in cases where the scan is inconclusive, or where there is suspicion that the placenta has invaded adjacent organs. The features which suggest accreta are:

uterine bulging

heterogenous signal density within the placenta

dark intraplacental bands on T2-weighted imaging.

Measurement of cell-free placental messenger RNA (mRNA) in the maternal plasma has been described as a means of improving the accuracy of the diagnosis, but is not clinically available. Elevated levels of alpha fetoprotein, free beta-human chorionic gonadotrophin and creatine kinase have also been associated with accreta, but are not advocated as screening or diagnostic tests.

Despite these investigations, it is not possible to diagnose or exclude placenta accreta with certainty in the antenatal period, and if the placenta still appears to overlie the scar at 32 weeks the management plan for a woman with a previous CS should assume that there is a risk of accreta.

Management

Any pregnant woman with a low anterior placenta or a placenta praevia and a previous CS is at risk of major haemorrhage and should have a regular assessment of full blood count (give iron supplements where appropriate). Care should be consultant based and follow the Placenta Praevia after Caesarean Section care bundle:

consultant obstetrician planned and directly supervising the delivery

consultant anaesthetist planned and directly supervising anaesthesia at delivery

blood and blood products available on site

multidisciplinary involvement in preoperative planning

discussion and consent including possible interventions (such as hysterectomy, leaving the placenta in situ, cell salvage and interventional radiology)

local availability of level 2 critical care bed.

The optimal timing of delivery depends on the clinical features but is generally advocated around 37 weeks to reduce the risks of an emergency procedure should labour start spontaneously or heavy antepartum haemorrhage occur. It is advisable to administer steroids to improve fetal lung maturity.

Multidisciplinary discussion should involve:

theatre staff to plan equipment required, such as cell salvage and additional instruments for hysterectomy and balloon tamponade

interventional radiologists to decide if preoperative placement of femoral balloons is required, advise on imaging modalities required in theatre or to be on standby should the need arise

anaesthetists to plan anaesthesia technique and equipment required, to liaise with critical care

haematologist to alert laboratory staff to possible need for large amounts of blood and clotting factors

consideration of the need for other surgical support: gynaecologist, vascular surgeon, urologist

neonatal team, especially if surgery has to take place away from the normal theatre to allow access for interventional radiology.

It is advisable to draw up a checklist with the names and contact details of all involved in the case. This should be in the patient’s notes in case labour starts prior to the planned date.

The consultant obstetrician should discuss plans with the woman and her partner, and document these in the notes. If their family is complete and the placenta does not readily separate, then immediate hysterectomy leaving the placenta in place is the best course of action. If the woman wishes to preserve her fertility, then it may be possible to leave the placenta in situ, and close the uterus. She must understand that hysterectomy may still be required, and she will have to attend for prolonged follow up; there is also a risk of infection to consider.

A retrospective, multicentre study in France from 1993–2007 reviewed 167 cases of accreta treated conservatively. Management was successful in 78%, spontaneous placental resorption occurred in 75% of these women – taking a median of 13.5 weeks (range 4–60 weeks). One woman died of complications related to administration of methotrexate. There were 21 successful subsequent pregnancies, but placenta accreta recurred in six pregnancies.

Surgical considerations

Ideally, the uterus should be opened avoiding the placenta; a vertical skin incision may be required. It is good practice to confirm the placental position by ultrasound scan immediately prior to the operation. If necessary, a scan probe can be covered with a sterile sleeve and used directly on the uterus intraoperatively. Exteriorisation of the uterus and a posterior uterine wall incision has been performed in cases where the placenta covers the entire anterior uterine wall.

If the placenta does not separate following administration of Syntocinon, the cord should be unclamped and drained of blood, and the cord ligated close to the placenta and cut short, and the uterine incision should be closed. Depending on the patient’s wishes and clinical needs, hysterectomy or conservative treatment follows as appropriate. Prophylactic antibiotics are needed for a few days if the placenta is left in situ. Serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels should be checked twice weekly, together with full blood count and C-reactive protein levels to look for signs of infection, and the woman kept under close review. Methotrexate has been used with varying degrees of success. As it precludes breastfeeding it should not be routinely used, but may be considered if the beta hCG levels do not fall.

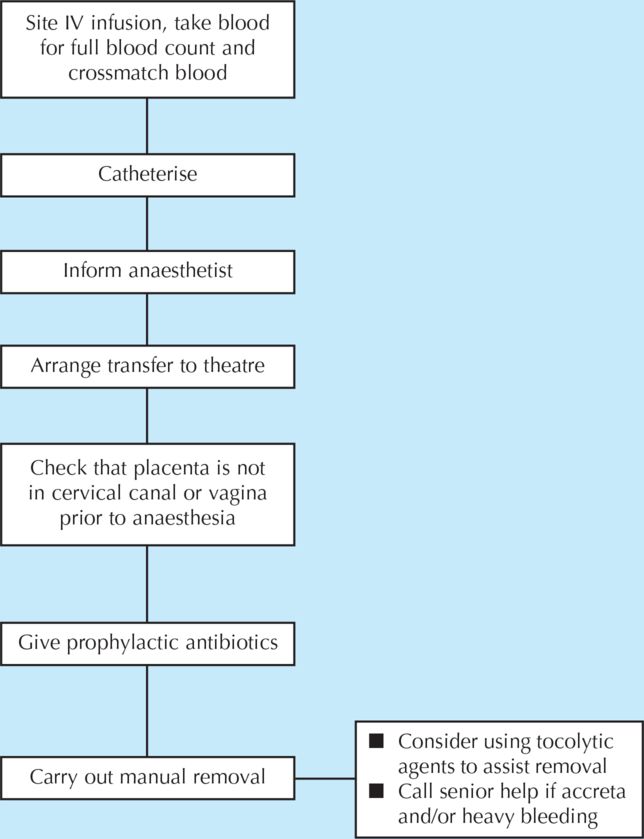

In the situation where accreta was not anticipated, surgical entry has failed to avoid the placenta, or the placenta partially separates and bleeding ensues, the situation is more hazardous and associated with heavy bleeding. In these situations, it is advisable to remove the placenta as best possible, small portions of myometrium can be removed/sutured to reduce bleeding and local infiltration of uterotonics or balloon tamponade may be helpful. Hysterectomy is, however, likely to be needed in up to 50% of such cases and recognising this and performing it in a timely fashion, before the patient is in extremis, can be lifesaving. See Algorithm 27.1 for a diagrammatic representation of the management of placenta accreta.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree