Chapter 5 Physiological and anatomical changes in pregnancy

HORMONAL CHANGES

Most of the anatomical changes that occur in pregnancy are due to the hormones secreted by the placenta. These hormones and their effects on the woman’s body are described in Chapter 3. In addition, other endocrine glands synthesize hormones, in different quantities during pregnancy compared with the non-pregnant state. These changes are briefly described below.

GENITAL TRACT CHANGES

Uterus

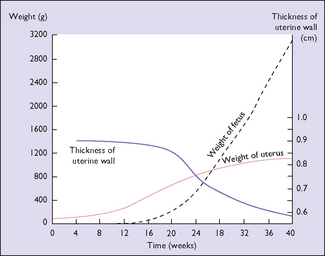

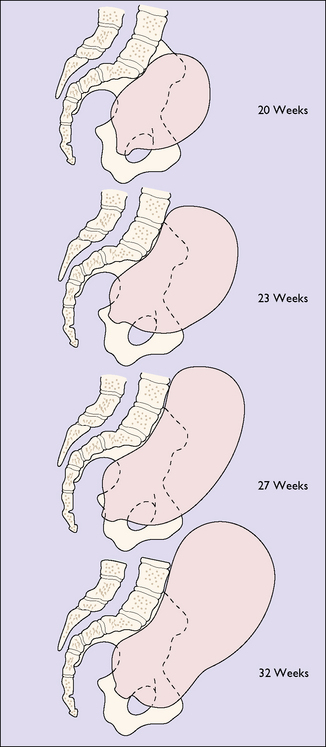

The effect of the hormonal stimulation is most marked upon the tissues of the genital tract, and the uterine muscle fibres grow to 15 times their prepregnancy length during pregnancy, whereas uterine weight increases from 50 g before pregnancy to 950 g at term (Fig. 5.1). In the early weeks of pregnancy the growth is by hyperplasia, and more particularly by hypertrophy of the muscle fibres, with the result that the uterus becomes a thick-walled spherical organ. From the 20th week growth almost ceases and the uterus expands by distension, the stretching of the muscle fibres being due to the mechanical effect of the growing fetus. With distension the wall of the uterus becomes thinner and the shape cylindrical (Fig. 5.2). The uterine blood vessels also undergo hypertrophy and become increasingly coiled in the first half of pregnancy, but no further growth occurs after this, and the additional length required to match the continuing uterine distension is obtained by uncoiling the vessels.

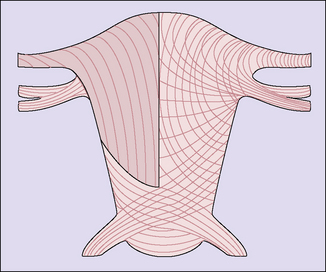

The effect of the uterine distension is to stretch both interdigitating spiral systems and to increase the angle of crossing of the fibres, in the thinner lower segment area where the fibres cross at an angle of about 160 ° and are less stretched. Incision of the myometrium in this zone is anatomically more suitable, and experience of lower segment caesarean section confirms that healing is better (Fig. 5.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree