Chapter 7 Physiological and anatomical changes in childbirth

THE PASSAGES

Bony pelvis

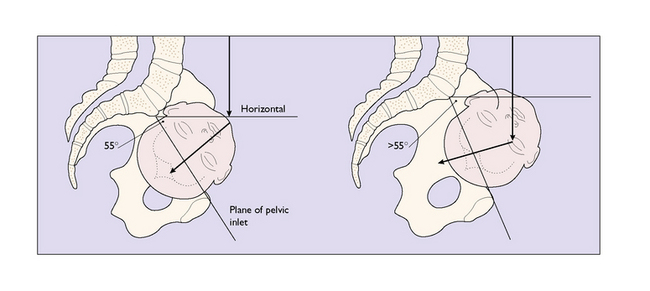

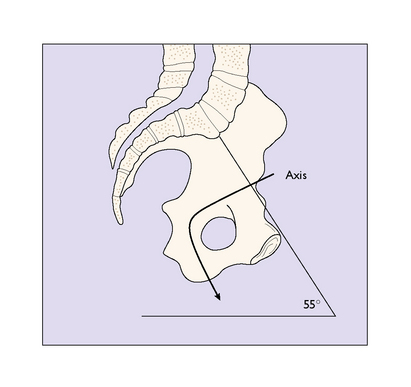

The bony pelvis is made up of four bones, the two innominate bones, the sacrum and the coccyx, united at three joints. When a woman stands erect, the pelvis is tilted forward. The pelvic inlet makes an angle of about 55 ° with the horizontal. The angle varies between individuals and between races; for example, black Africans have a lesser angle. An angle of more than 55 ° may make the descent of the fetal head into the pelvis difficult (Fig. 7.1).

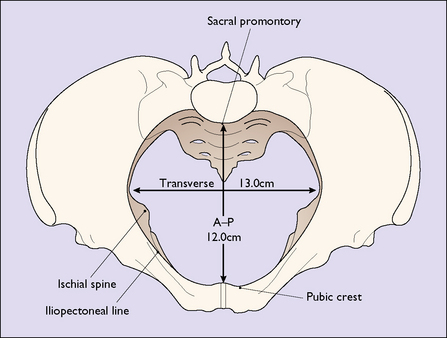

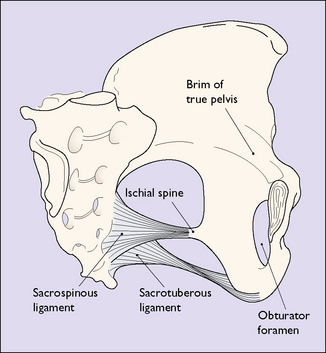

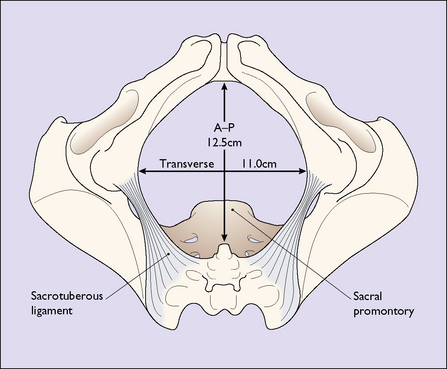

The ‘true’ pelvis is bounded by the pubic crest, the iliopectineal line and the sacral promontory. An ‘ideal obstetric’ pelvis is described in Box 7.1 and the brim is shown in Figure 7.2. The true pelvis is cylindrical in shape, with a bluntly curved lower end, and is slightly curved anteriorly. Anteriorly the pubic bones form its boundary, measuring 4.5 cm. Posteriorly, the curve of the sacrum forms its boundary, measuring 12 cm. Laterally its walls narrow slightly distally (Fig. 7.3). The walls are penetrated by the obturator foramen anteriorly and the sciatic foramen laterally, which is divided into two parts by the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments.

Box 7.1 The ideal obstetric pelvis

| Brim | Round or oval transversely |

| No undue projection of the sacral promontory | |

| Anterior–posterior diameter 12 cm | |

| Transverse diameter 13 cm | |

| The plane of the pelvic inlet not less than 55 ° | |

| Cavity | Shallow with straight side-walls |

| No great projection of the ischial spines | |

| Smooth sacral curve | |

| Sacrospinous ligament at least 3.5 cm | |

| Outlet | Pubic arch rounded |

| Subpubic angle > 80 ° | |

| Intertuberous diameter at least 10 cm |

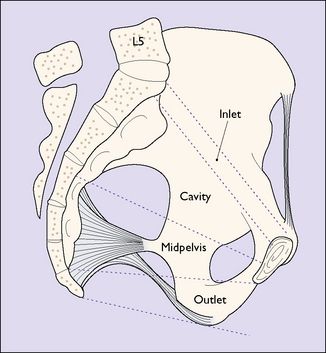

For descriptive purposes the true pelvis can be divided into four zones. These are shown in Figure 7.4. The measurements of the zone of the inlet are shown in Figure 7.2. The zone of the cavity is wedge-shaped in profile and almost round in section. It is the most roomy part of the true pelvis, the anterior–posterior diameter measuring 13.5 cm and the transverse diameter 12.5 cm.

The zone of the outlet (Fig. 7.5) does not usually interfere with the birth unless the pubic rami are narrow, which reduces the intertuberous diameter. In these cases delay may occur and the soft tissues of the perineum may be torn and damaged.

The axis of the birth canal corresponds to the direction the fetal presenting part – usually the head – takes during its passage through the birth canal (Fig. 7.6).

Soft tissues of the female pelvis

These include the uterus, the muscular pelvic floor and the perineum. The anatomical details are described in Chapter 43.

Uterus

The uterus in pregnancy can be divided into three parts:

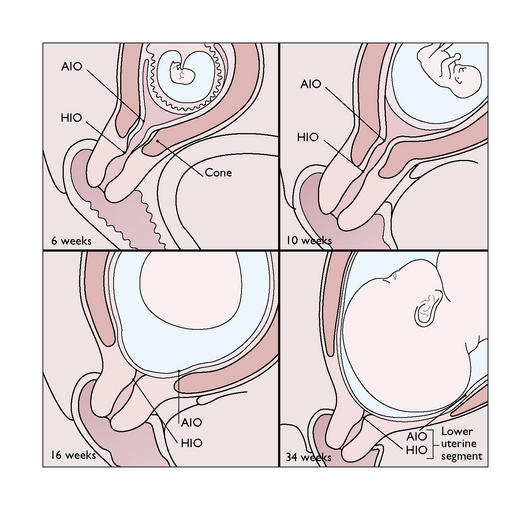

Lower uterine segment

This portion of the uterus lies between the vesico-uterine fold of the peritoneum superiorly and the cervix inferiorly. During pregnancy the upper part of the cervix is incorporated into the lower uterine segment, which stretches to accommodate the fetal presenting part (Fig. 7.7). In late pregnancy, as the upper segment muscle contractions increase in frequency and strength, the lower uterine segment develops more rapidly and is stretched radially to permit the fetal presenting part to descend (Fig. 7.8). In labour the entire cervix becomes incorporated into the stretched lower uterine segment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree